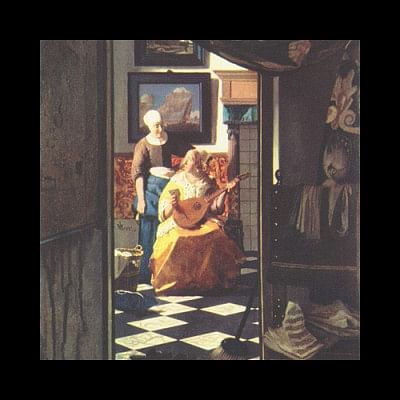

Vermeer Thefts: 1971-The Love Letter

The thief locked himself in an electrical box in the exhibition hall and, once the museum was closed, he pulled the painting from the wall and made for a window. When the frame was too large to go through the window and because he was unable to extract the canvas quickly from the frame, he clumsily slashed the painting out of its frame with a potato peeler. He then tucked the painting into the back of his trousers where it sustained further damage. At first, Roymans hid the canvas in his room; later, he buried it in the forest. When it began to rain, he dug the painting up and put it in a pillowcase hiding it under the bed mattress of his room in the café-restaurant of the Soetewey Hotel where he worked.

Roymans conceived his plan after he had seen television images of the humanitarian disaster in East Pakistan, probably the first time that viewers were confronted with such a humanitarian disaster. The 1971 Bangladesh genocide involved bloodshed and human rights abuses in East Pakistan during the Bangladesh Liberation War. Massacres, killings, rape, arson and systematic elimination of religious minorities (particularly Hindus), political dissidents and the members of the liberation forces of Bangladesh were targeted by the Pakistan Army with support from paramilitary militias. The idealist waiter from Limburg, Belgium, felt that something had to be done for the victims of the disaster.

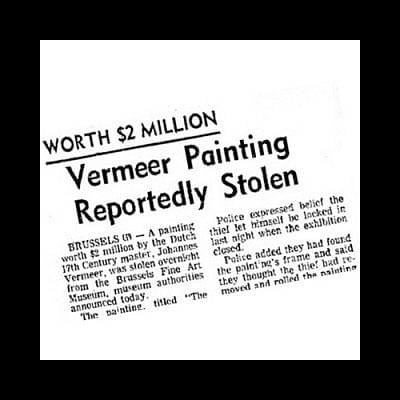

The robbery became world news, and a massive hunt for the precious work ensued.

On the night of 3 October in 1971, Roymans, who called himself "Tijl van Limburg," after a legendary hero who helped the poor in Robin Hood style during the 16th century Spanish Inquisition, contacted a reporter from the Brussels newspaper Le Soir and arranged a predawn meeting in a pine forest near Zolder (Belgium Limburg). On the cold, foggy early morning, the reporter waited for Roymans in his car. As instructed, he had brought his camera along. After half an hour, Roymans, medium height and thin, appeared out of nowhere and greeted the reporter with his face covered by a plastic mask.

He opened the door of the car, pushed the reporter over to the passenger's side, sat behind the wheel and instructed the reporter to put on a blindfold. Roymans drove for a half hour through the predawn fog before parking the car in front of a small church. Getting out, Roymans told the reporter to wait. Soon after, Roymans returned with the painting wrapped in a white cloth. He allowed the reporter to take about ten photographs by the car headlights to prove he actually had the painting. The reporter was again blindfolded, and while driving back, Roymans, who by this time seemed to have relaxed considerably, began to talk freely. He confessed that he loved art and would have given ten years of his life to keep the painting but knew he couldn't. He said that he also loved humanity and felt he had to do something to alleviate human suffering.

A photograph of the painting was published along with Roymans' three conditions for the painting's return: (1) that 200 million Belgian francs be given to Bengali refugees in East Pakistan who had been suffering desperate famine, (2) the Rijksmuseum should organise a campaign in the Netherlands to raise money to combat world famine, and (3) the Palace of Fine Arts in Brussels should do the same in Belgium. Roymans set the deadline for Wednesday, 6 October.

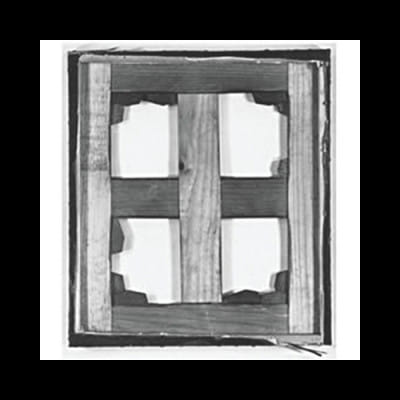

The morning after publication, the police arrived at the Le Soir headquarters demanding an explanation for why they had not been contacted before the meeting with Roymans. The police confiscated the photographs and secured the help of art experts to examine them to determine if they represented the real painting. It was determined that they were, indeed, photos of the cherished Love Letter.

As anxiety mounted in the days that followed, Roymans made many other phone calls to newspapers and radio stations.

According to the Dutch art historian and Vermeer expert Albert Blankert, Roymans' demands were "alarmingly well received" by the Dutch public. Petitions were circulated urging authorities to rescind the warrant for his arrest and there were spontaneous initiatives in favour of the refugees from East Pakistan. A wave of sympathy spread across the country, and slogans in favor of Roymans' cause were seen chalked on bridges and walls.

Roymans telephoned the Belgium newspaper Het Voljk saying that unless a contract meeting the ransom demands were signed on a live television broadcast, he would sell the painting to an anonymous American art collector.

Finally on 6 October, the deadline day of his demands, Roymans was arrested in eastern Belgium soon after he made a telephone call to the Belgium newspaper from a public telephone at a gas station. Annie Mommens, the wife of the service station owner, overheard Roymans' call, and as the man rode off on his motorcycle, telephoned the police while Mr Mommens chased him in his car. According to Mr Mommens, when Royman saw him meeting the police along the road," he panicked, jumped off his motorcycle and ran across a field towards a farm. He hid in a cowshed underneath the straw. That's where I grabbed him."

Roymans was hiding between two cows. The two-week ordeal was over. He immediately led the police to his room where he kept the painting.

Mark Durwael, the son of the owner of the Soetewey Hotel where Roymans stayed, described Roymans as "a neat, courteous and a good worker." "But he had a passion for Pakistan. Every time work slacked off he began talking about the sad plight of the Bengali refugees."

After his arrest, the Limburg Robin Hood had more than ever the public on his side. Newspapers and radios received many letters and messages in his support.

The Love Letter was delivered to the Rijksmuseum on 8 October and was shown to the press on 11 October. Since the painting had been seriously damaged, an international committee was formed to oversee the restoration. The committee decided to restore the lost and damaged parts as faithfully as possible in order to maintain the painting's accentuated illusionist quality. The heist lasted short of two weeks; the restoration took almost a year.

Roymans was brought to trial on 20 December and sentenced on 12 January by the Brussels court to a fine and two years in jail although he served only six months. After his release, he married and had a child. He suffered from severe depression, and his marriage failed. He began living in a car and on Boxing Day, 1978, he was found sick in his car along a road near Liege gravely ill. Ten days later, on January 5, 1979, he died at the age of 29.

Belgian musician and film director Stijn Meuris, who had long been fascinated by the story of Roymans, later made an empathetic documentary of the case.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments