Philippine banks seen to address vulnerabilities vs fraud

Philippine banks are seen to reexamine vulnerabilities to potential fraudsters in order to avoid a repeat of the $81-million money-laundering scandal that has now become a global spectacle.

Asked what the local banking industry would likely change on the heels of the money-laundering case involving the Jupiter branch of Rizal Commercial Banking Corp., Banco de Oro Unibank president Nestor Tan said there were typically three areas where things could go wrong: Poor processes, poor compliance and collusion.

Tan, who is also the president of the Bankers Association of the Philippines, explained that an institution would have "poor" processes if it did not have the right checks and balances and internal control processes.

On the other hand, he said "poor" compliance with defined processes and procedures would happen when "somebody is supposed to check it and that person doesn't check it."

Another vulnerability could arise from "collusion" between bank personnel and money launderers, he added.

"A typical bank will probably look at all three—strengthen their processes and make sure that they are in place and they are adequate, set the tone at the top for compliance with processes, and make sure you have zero tolerance for deviations on this," Tan said.

Once in a while, he said there could be lapses because "we're all humans," which was why there must be "checkers."

"Violations and gross negligence are the things that you must be tighter on," he said.

"Collusion is a difficult thing to prevent. I don't know the answer but the more you can segregate the (transaction) maker and the checker and the more you do the checking outside the branch, the better off you are," Tan said. "Bottomline is, it will not be easy to have zero instances but you can prevent the number of instances or the impact of the instances."

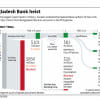

On February 5, some $81 million in dirty money stolen by computer hackers from the Bangladesh central bank entered the Jupiter branch of RCBC and found its way to local casinos, which are not covered by reporting obligations under the Philippine anti-money laundering law. This is now the subject of an ongoing investigation by the Senate blue ribbon committee.

Tan's brother, Lorenzo, is the president of RCBC, the bank involved in the money-laundering controversy. Maia Santos-Deguito, the former manager of the Jupiter branch, had been accused of facilitating the creation of the fictitious bank accounts that received the dirty money, working on their speedy withdrawal. Deguito had argued that she was but a scapegoat in this case.

Asked what reforms could be introduced to the country at this time, Tan said this issue was "more legislative" than a "regulatory" procedural issue.

Conventional theory states that the international syndicate that planned the Bangladesh cyber heist chose the Philippines as destination of the dirty money because casinos are not covered by reporting obligations under the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA). Tan noted that the banking industry and the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas were "both caught between the Bank Secrecy Act and the AMLA regulations."

"You have to appreciate that AMLA rules can only be implemented by procedures and (through the) exercise (of) good judgment. Banks can't assure legality of the nitty gritty of the transaction," Tan said.

Copyright: Philippine Daily Inquirer/ Asia News Network

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments