Extending life: Ways to live past 100

The dream of living forever permeates human culture. Mythical tales of immortals are found everywhere from the Greek myths and alchemist's notebooks to modern movies and futuristic science-fiction books. As the science of aging progresses, scientists have made tremendous progress in extending human life reports livescience.com

From lowering infant mortality rates to creating effective vaccines and reducing deaths related to disease, science has helped increase the average person's life span by nearly three decades over the past century, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Where will the future of genetic engineering and regenerative medicine take us? No one knows, but researchers are narrowing down the places to look for that next fountain of youth.

1.Have the right stuff

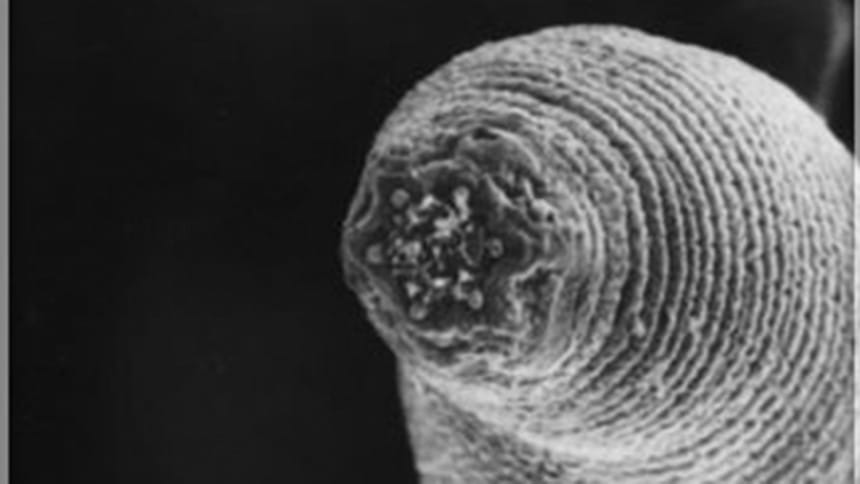

Back to researchers' favorite worms, the nematode C. elegans. Multiple proteins linked to longevity have been isolated in the lab worm. For example, a study published in May 2010 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry indicated that a protein called arrestin directly regulates lifespan. Being born with no arrestin meant the worms lived a third longer than usual, while being born with extra meant the worms' lives were cut short by a third.

Previous studies have also shown that decreased activity of the so-called insulin-like growth factor pathway can also increase longevity in worms, a link that held up in fruit flies, mice and even humans — for example, it's linked to increased lifespan in Ecuadorians with Laron's syndrome.

The jury is still out on how these proteins and other life-extending or -depleting compounds found in rodent studies will affect human longevity. A study published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society in August 2011 indicates that centenarians live just as unhealthy lives as the rest of us. One woman, at age 107, smoked for over 90 years. This indicates that genetics probably plays a large role in what makes a centenarian live so long, but the researchers note you shouldn't fall off the wagon and start tossing down doughnuts for breakfast; remember that genetics is a game of chance.

2. Avoid bachelorhood

Need an excuse to get married? For guys, the result could mean a longer life. Data from the "Longevity Project" book indicates that men who got and stayed married were likely to live beyond age 70, but less than one-third of divorced men made it to that age. Men who never married outlived those who divorced, but not those who stayed married.

The effect is smaller in women, but still there. On average, married men live 10 years longer than non-married men, and married women lived about four years longer than non-married women. There are several hypotheses for these differences: Married men might adopt healthier lives and take fewer risks, or their wives may help them stay connected to their social circle, since being social has a positive impact on lifespan.

3. Be an Ecuadorian dwarf

Genetics plays a big role in our expected lifespan. A study of Ecuadorians with Laron syndrome, which causes dwarfism, shocked scientists when they realized that these short-statured South Americans were essentially resistant to cancer and diabetes.

The disease is caused by a mutation in a protein that regulates how cells grow and divide. And it turns out the mutation's effect on a growth-signaling pathway in the body also leads to resistance to cancer and diabetes.

Though none of the Laron group died of these two age-related diseases, they didn't live any longer than their unaffected relatives — instead, the study found they had higher rates of death from various accidents and alcohol-related issues. Still, after extended study in lab animals, the study points to this growth-factor pathway as an important regulator of lifespan in humans.

4. Be hardworking

Taking it easy may be the key to a relaxing vacation, but it isn't the key to a long life, according to research finding that hard-working, prudent humans live the longest. The study followed more than 1,500 children from the 1920s until their death.

Analysis of the longevity of this group of children was published in March 2011 in the book "The Longevity Project: Surprising Discoveries for Health and Long Life from the Landmark Eight-Decade Study" (Hudson Street Press). It indicates that dependable, prudent children on average avoided risks and eventually entered into stable relationships — a major boost for health, happiness and longevity.

The conscientious, hard-working personality trait extends life by an average of two to three years, the equivalent to a 20 percent to 30 percent decreased risk of early death.

5. Have healthy parents

You are what you eat, and, it turns out, you might also be what your parents eat. A study in rats presented in April 2010 at the American Association for Cancer Research meeting, indicates that what your parents are exposed to, through their food and other toxins in the environment, can impact not only their health but the health of their offspring. Specifically, rat diets high in omega three fatty acids during pregnancy left not only daughter rats, but also granddaughter rats at an increased risk for breast cancer.

A similar study in mice (published in the journal Cell in December 2010) indicated that a father's diet could influence the expression of hundreds of genes in his offspring, including those genes involved in fat- and cholesterol-processing in the liver.

These types of changes to gene expression are called epigenetic changes. Instead of changing the genes themselves, epigenetic changes alter how the genes are accessed and used. New research published in the journal Nature in 2011, indicates that, at least in worms these epigenetic changes (which in that study increased the worm's lifespan) can be passed down to offspring for several generations. Researchers had previously thought that the epigenetic slate gets wiped clean when sperm meets egg.

6. Starve yourself

Reducing calories in your diet could help you live longer, if you are a worm or a mouse. The effects of a reduced-calorie diet are still debated in humans, though. Recent research in the Journal of Nutrition, published in January 2009, added another layer to the caloric-restriction debate: In the study, naturally chubby mice lived longer when fed reduced-calorie chow than lean mice that ate the low-cal food.

Previous studies have indicated that lab animals, like the nematode C. elegans, the fruit fly Drosophila and lab mice, all lived almost twice as long when fed an almost-starving diet (30 percent fewer calories than usual), but the effect on humans isn't clear. A study published in July 2008 indicated that eating less could add five years to the life of an average human.

The restricted diet seems to work by lowering metabolic rate, reducing the frequency of age-related diseases by reducing the amount of "free radicals" produced naturally by our bodies. This may happen by reducing levels of thyroid hormone, the study in the June 2008 issue of the journal Rejuvenation Research suggested.

7. Kick old cells to the curb

The adage "out with the old and in with the new" could help prevent age-related diseases if applied to certain cells, suggests a study on mice, published in the journal Nature in November 2011.By removing the body's worn-out cells, called senescent cells, several times during the lifetime of aging-accelerated mice, researchers were able to spare the mice of cataracts, aging skin and muscle loss.

These comatose cells send out chemical signals that have a strange impact on the cells around them, and researchers have speculated that these chemicals can lead to age-related diseases. Compared with mice that kept all their senescent cells, mice undergoing spring-cleaning of old cells had stronger muscles, fewer cataracts and less wrinkled skin (because their fat deposits in their skin were in better shape).

Even if their treatment started at middle age, deterioration of the subject's muscle and fat cells was nearly stopped when the researchers started removing their senescent cells. Such an approach, if validated, could be used to help develop a vaccine to prime the immune cells to attack senescent cells.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments