Why Delhi buys water on the black market

In the congested Delhi neighbourhood Sangam Vihar, home to 500,000 people, the air is fraught with anticipation.

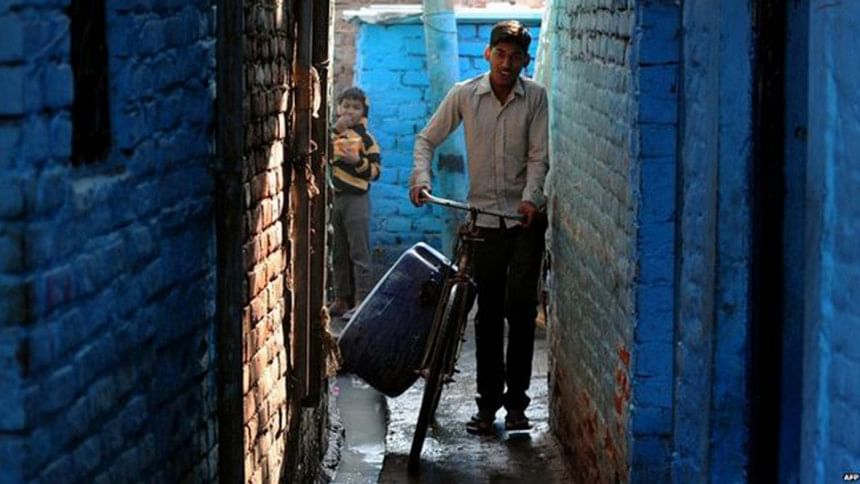

Rows of men and women are gathered in its narrow lanes, some sitting on their haunches. Large plastic drums are placed strategically in front of them.

Suddenly a cry goes up: "It's here, it's here."

A water tanker backs into the lane, and the place descends into chaos.

Young men charge towards the truck, clambering onto the top with pipes, which are then lowered into the tank. Others push the drums in place - there's a mad scramble to fill them up with clean water.

Fights break out as some people are pushed out of the way.

"It's always like this," Jainisha Khatoon says. "People push and pull. We get abused. That's when I step back."

In 15 minutes, the water runs out and the tanker drives away, leaving many desperate people behind.

"It only comes once every 10 days or so," says Rupa Jha, another resident.

"How do you expect it to last? We have to buy water from private suppliers. Water's always available but at a price."

About 20 percent of Delhi's population have no access to piped water and have to be supplied by water tankers. But the difference between demand and supply is more than 750 million litres a day.

So they have to rely on the black market - water supplied by private contractors, or "the water mafia", as it has come to be known.

"It's always existed here. A network of people who steal water and then supply it to those who need it," says Anuj Porwal, a social activist from Sangam Vihar.

"They have the backing of the police and local politicians. That's why no one can stop them," he alleges.

The allegations have always been denied.

It costs about $10 (£6) to buy 200 litres of water from the mafia. In contrast, water provided by the city government is free, when available.

"I make about $80 a month. So you can imagine how hard it is for us to come up with that kind of cash," says Bimla, another resident of the area.

Under the cover of darkness, the mafia works to bridge the gap between supply and demand.

It is 04:00 at Balla, a sandy enclave by the banks of the Yamuna river that flows through Delhi.

The single street, with a few shops and houses on either side, is deserted save for a few stray dogs.

It's also dark - most of the streetlights are switched off or are missing.

A row of tankers snake through the street and then pull into one of several alleys. Men jump out and quickly haul thick pipes which are then rigged into the tanks.

The other end of the pipes are attached to borewells sunk deep into the ground. With a low hum, thousands of litres of water are pumped into the trucks.

It takes less than half an hour to fill up a truck. As one leaves, another takes its place. Details are entered into a logbook.

It's a well organised operation that is conducted swiftly and stealthily.

"No one really challenges them because they can be dangerous," one local resident warns us.

The men themselves are reluctant to talk.

When one does, he offers this by way of explanation: "We only supply water to those areas that need it."

The immediate fallout of this informal, but shadowy, syndicate is that many of Delhi's residents - especially its poorest - are paying a price for a resource that's meant to be freely available.

But there's a long-term impact too.

The mafia is drawing out water from India's groundwater, which is slowly being critically depleted.

If unchecked it could lead to a potentially devastating social and economic cost.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments