Smart insulin patch could replace painful injections

Painful insulin injections could become a thing of the past for the millions of Americans who suffer from diabetes, thanks to a new invention from researchers at the University of North Carolina and NC State, who have created the first "smart insulin patch".

The patch that can detect increases in blood sugar levels and secrete doses of insulin into the bloodstream whenever needed, reports Science Daily.

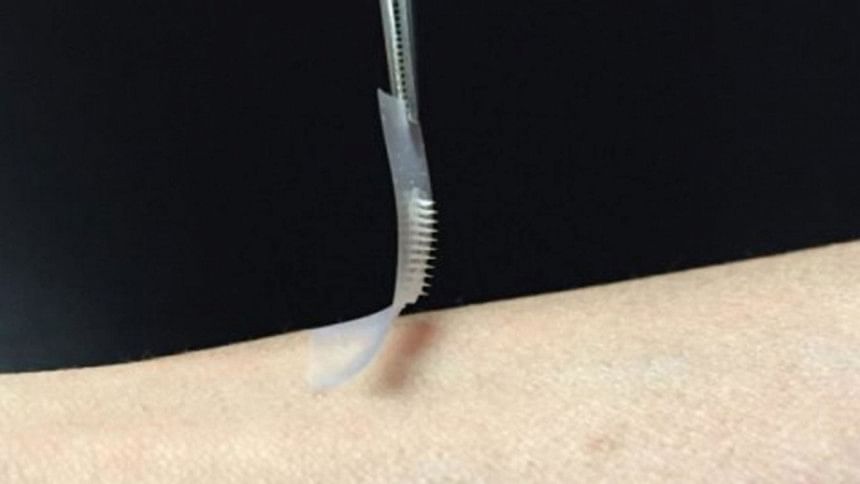

A thin square no bigger than a penny, the patch is covered with more than one hundred tiny needles, each about the size of an eyelash. These "microneedles" are packed with microscopic storage units for insulin and glucose-sensing enzymes that rapidly release their cargo when blood sugar levels get too high.

The study, which is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that the new, painless patch could lower blood glucose in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes for up to nine hours. More pre-clinical tests and subsequent clinical trials in humans will be required before the patch can be administered to patients, but the approach shows great promise.

"We have designed a patch for diabetes that works fast, is easy to use, and is made from nontoxic, biocompatible materials," said co-senior author Zhen Gu, PhD, a professor in the Joint UNC/NC State Department of Biomedical Engineering. Gu also holds appointments in the UNC School of Medicine, the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, and the UNC Diabetes Care Center.

"The whole system can be personalised to account for a diabetic's weight and sensitivity to insulin," he added, "so we could make the smart patch even smarter."

Diabetes affects more than 387 million people worldwide, and that number is expected to grow to 592 million by the year 2035. Patients with type 1 and advanced type 2 diabetes try to keep their blood sugar levels under control with regular finger pricks and repeated insulin shots, a process that is painful and imprecise.

John Buse, MD, PhD, co-senior author of the PNAS paper and the director of the UNC Diabetes Care Center, said, "Injecting the wrong amount of medication can lead to significant complications like blindness and limb amputations, or even more disastrous consequences such as diabetic comas and death."

Researchers have tried to remove the potential for human error by creating "closed-loop systems" that directly connect the devices that track blood sugar and administer insulin. However, these approaches involve mechanical sensors and pumps, with needle-tipped catheters that have to be stuck under the skin and replaced every few days.

Instead of inventing another completely humanmade system, Gu and his colleagues chose to emulate the body's natural insulin generators known as beta cells. These versatile cells act both as factories and warehouses, making and storing insulin in tiny sacs called vesicles. They also behave like alarm call centers, sensing increases in blood sugar levels and signaling the release of insulin into the bloodstream.

"We constructed artificial vesicles to perform these same functions by using two materials that could easily be found in nature," said PNAS first author Jiching Yu, a PhD student in Gu's lab.

The first material was hyaluronic acid or HA, a natural substance that is an ingredient of many cosmetics. The second was 2-nitroimidazole or NI, an organic compound commonly used in diagnostics. The researchers connected the two to create a new molecule, with one end that was water-loving or hydrophilic and one that was water-fearing or hydrophobic.

A mixture of these molecules self-assembled into a vesicle, much like the coalescing of oil droplets in water, with the hydrophobic ends pointing inward and the hydrophilic ends pointing outward.

The result was millions of bubble-like structures, each 100 times smaller than the width of a human hair. Into each of these vesicles, the researchers inserted a core of solid insulin and enzymes specially designed to sense glucose.

In lab experiments, when blood sugar levels increased, the excess glucose crowded into the artificial vesicles. The enzymes then converted the glucose into gluconic acid, consuming oxygen all the while. The resulting lack of oxygen or "hypoxia" made the hydrophobic NI molecules turn hydrophilic, causing the vesicles to rapidly fall apart and send insulin into the bloodstream.

Once the researchers designed these "intelligent insulin nanoparticles," they had to figure out a way to administer them to patients with diabetes. Rather than rely on the large needles or catheters that had beleaguered previous approaches, they decided to incorporate these balls of sugar-sensing, insulin-releasing material into an array of tiny needles.

Gu created these "microneedles" using the same hyaluronic acid that was a chief ingredient of the nanoparticles, only in a more rigid form so the tiny needles were stiff enough to pierce the skin. They arranged more than one hundred of these microneedles on a thin silicon strip to create what looks like a tiny, painless version of a bed of nails. When this patch was placed onto the skin, the microneedles penetrated the surface, tapping into the blood flowing through the capillaries just below.

The researchers tested the ability of this approach to control blood sugar levels in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes. They gave one set of mice a standard injection of insulin and measured the blood glucose levels, which dropped down to normal but then they quickly climbed back into the hyperglycemic range.

In contrast, when the researchers treated another set of mice with the microneedle patch, they saw that blood glucose levels were brought under control within thirty minutes and stayed that way for several hours.

In addition, the researchers found that they could tune the patch to alter blood glucose levels only within a certain range by varying the dose of enzyme contained within each of the microneedles. They also found that the patch did not pose the hazards that insulin injections do. Injections can send blood sugar plummeting to dangerously low levels when administered too frequently.

"The hard part of diabetes care is not the insulin shots, or the blood sugar checks, or the diet but the fact that you have to do them all several times a day every day for the rest of your life, said Buse, the director of the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences (NC TraCS) Institute and past president of the American Diabetes Association. "If we can get these patches to work in people, it will be a game changer."

Because mice are less sensitive to insulin than humans, the researchers think that the blood sugar-stabilizing effects of the patch could last even longer when given to actual patients. Their eventual goal, Gu said, is to develop a smart insulin patch that patients would only have to change every few days.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments