Integrated resource planning and the power sector

Integrated Resource Planning (IRP) is a planning approach that has the potential to take a society-wide perspective, incorporate public participation in meaningful ways, and has a strong track record in creating plans that are low-cost, low risk, and with outcomes that minimise environmental and social impacts'.

Integrated Resource Planning requires addressing both supply side and demand side management for an efficient use of energy. Despite proven advantages of IRP over conventional power development plans, many countries ignored IRP and paid high price. Several US states and other countries have now made it law for utilities to follow IRP. As efficiency improvement reduces generation and hence utility revenue, it may encourage traditionalists to stick to an inefficient system. At the same time a MW added has a huge political mileage than a MW saved.

Conventional planning typically focuses on least cost generation options. It is purely done from a financial perspective. Projecting an economic growth, electricity demand is forecasted typically with a time tag. Accordingly, a set of peaking, intermediate and base load power plants are planned dominated by few large power plants. Matching generation with actual demand is a challenge that typically ends with either a surplus or a shortage. The politicians and policy makers always get more concerned with MW of installation or capacity instead of the actual energy used in a day (MWhr). The conventional planning also always optimistically assumes a steady fuel cost and a lower discount rate. The investment options in a conventional planning is also limited and without much variation.

Conventional planning only considers the generation cost, whereas forty percent power system cost is the transmission. It also ignores the cost of environment degradation in its financial analysis. It focuses on large cluster of generation in a power hub whereas a distributed system could be more efficient. At the same time large power hubs away from the load centres make the system much more vulnerable for a possible blackout. The large power plants are almost always mired with cost and time over run. True economic cost of generation is never reflected in the tariff.

An IRP is a bottom up load calculation approach that requires analysis of energy growth in micro level and hence much more accurate in demand forecasting. The likelihood of shortage or surplus matching that demand is much less. Where conventional power development plan never looks at the demand side power management IRP pays detail attention on reducing demand through efficiency improvement and conservation.

When transmission and distribution cost is typically optimised after the generation decision in conventional planning, IRP includes them from the beginning. IRP considers the fuel price volatility, drought, carbon tax etc. Social and environmental externalities are inherent in integrated resource planning. IRP also involves people in its planning and development stage so that all development works are acceptable to the community. By and large conventional planning ignores these issues. Very few conventional plan talks about retirement or decommissioning of power plants in advance which create higher cost of production by either sudden shut down or continuation of inefficient aging plants.

Because energy efficiency is such a low-cost resource, IRP mandates that all energy efficiency options through demand side management are exploited. This also reduces total resource costs for utilities and a pillar stone of any IRP. In many countries, this is a requirement by the law. Unfortunately, the efficiency drive in both supply and demand side in Bangladesh has been missing. Only recently after the creation of SREDA, a serious study has been performed by JICA for the national energy efficiency and conservation plan (EE&C).

In the context of IRP if electricity demand forecast for Bangladesh is examined and all the efforts that are going on to meet that demand, it can be concluded that there is a huge knowledge gap in our planning. Bangladesh is also about to make the classical mistake of conventional planning.

The document in hand is the PSMP 2010 that predicts an electricity demand of about 34000 MW in 2030 based on government planning. This forecast is made on the basis of GDP growth and using a multiplier for electricity demand growth. The simplicity of such prediction is so attractive that most of the planners prefer this method. This approach has often predicted demand that has outstripped the real demand on the ground. In the Pacific Northwest of the US, such over-predictions of demand led to plans to build 20 nuclear and coal units, of which ultimately five coal plants and nine nuclear plants were scrapped. This cost the tax payers about USD 7 billion. In Thailand, similar inflated load forecasts (with a multiplier of 1.4) were blamed for 400 billion baht (USD 13 billion) accumulated overinvestment in the power sector (International RIVERS 2013).

Change of technology, efficiency improvement, demographic change, change in energy intensity of certain growth area and many other factors make the long term GDP to Electricity elasticity prediction very uncertain. IRP always takes a ground up approach including the following:

Energy end-use data

-Types of customers

-Types of equipment

-Amount of electricity use

Electricity sales records

-Customer class

-Geographical area

Demand records

-MW load over days to years

-Daily load curve and breakdown

-Seasonal variation

Economic and demographic historical data and projections

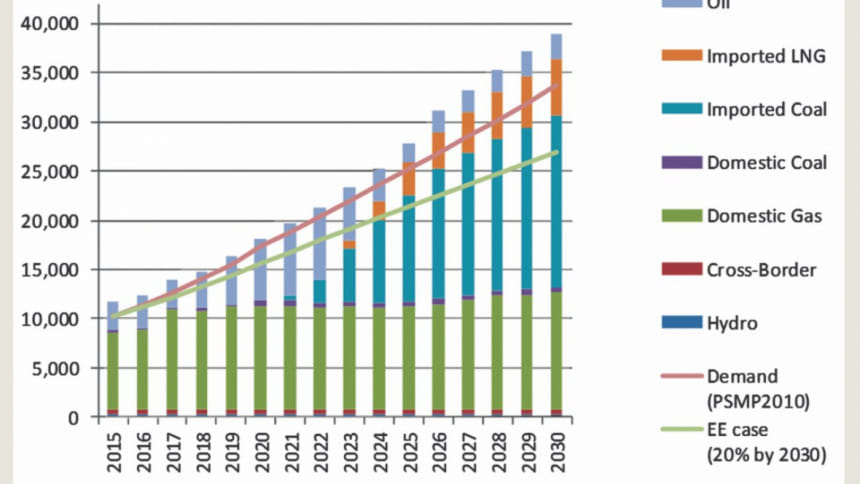

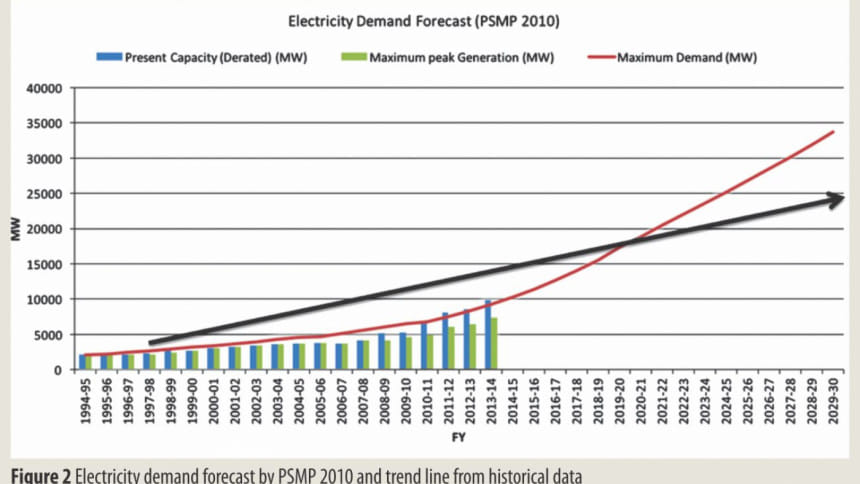

The IRP approach would challenge the prediction of PSMP 2010 on several grounds. The PSMP was done using a 7% GDP growth that predicted 10, 283 MW peak demand in 2010 whereas the real peak demand in 2015 was about 8500 MW. The EE&C study calculated an energy saving opportunity of 30% through various demand side efficiency improvement. Using a conservative approach, it predicted a 20% less peak generation requirement by 2030 amounting 27000 MW instead of 34000 MW (Figure1). If the current grid efficiency of 30% can be improved to 35%, the generation requirement in 2030 will reduce by another 5000 MW. Using a historical trend line on the higher side the prediction is less than 25000 MW peak demand in 2030 (Figure 2).

The PSMP 2010 is being revised for its fuel mix but not on the demand forecast. As a result, it is found in various discussions that cross border trading is being raised to 7000-9000 MW from the 3000 MW mentioned in PSMP 2010 and nuclear is being raised to 4000 MW from the current 2000MW in the new plan. The rest of the generation that was supposed to come from local coal is being compensated by imported coal.

The published plan for investment meeting the predicted demand runs into billions of dollars (USD 13 billion for 2400 MW nuclear, USD 2 billion for Rampal, USD 4.4 billion for Matarbari, USD 10 billion for other coal fired power projects). These do not include transmission and distribution cost. Conservatively at least USD 15 billion would be required to evacuate all the electricity to the load centres. Many of the projects have plans to add thousands of additional capacity in the same hub creating a nightmarish challenge for system balancing. If all the projects those are talked about or for even which MOU have been signed, the total generation from large base load plants adds up to almost 15000 MW already.

In the zest of adding power, the government should not get carried away by approving mega projects one after another. A solid home work based on painstaking micro analysis for a bottom up demand forecast along with giving serious consideration to the much cheaper demand side EE&C initiatives, the government can save huge resources, ease price escalation of power tariff and avoid embarrassment. Instead of adding large power projects first and then optimising the transmission and distribution network, an integrated system optimisation must be conducted identifying the present load centres and future growth areas for a least cost system rather than just least cost generation.

A poor country like Bangladesh cannot afford the conventional power development plan and pay a high price. By doing an integrated resource planning, Bangladesh can become the leader of a new world that would help leaving a more liveable planet for the next generation.

The writer is head of the department of petroleum and mineral resources engineering at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments