Female artists paving the way

Women have always been a common subject in visual art, but not so much in the role of an artist. For centuries, their thoughts and expressions remained hidden from public view and crushed under the weight of patriarchy. Yet, the female artists of today have etched out a place for themselves, breaking social and familial barriers, but that battle is still on in Bangladesh. We caught up with a few female artists of the country, to learn about their experiences.

Zeenat Wahid was one of the two women who completed her Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Faculty of Fine Art, DU (then known as East Pakistan College of Arts and Crafts), in 1966. She went on a three-day hunger strike to pursue her family for her enrolment at the institution. "I sat on our house's door sill, weeping and refusing to eat for three days, until one of my sisters took me to the college," reminisced the artist. Though her siblings were supportive of her passion, it was not easy to convince her conservative father. "For an entire year, my father knew I was studying sociology in Eden College," she said. She recounted how her siblings would put pillows under bed-sheets to make her father believe that Zeenat was at home, when she would actually be outdoors working with her classmates. She learned art from Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin, among others. Poet Sufia Kamal wrote the foreword in the catalogue of Zeenat's first solo exhibition in Dhaka in 1973, reflecting on the fact that women usually do not have the courage or advantages needed to practice art.

Moreover, security has always been a concern for women when it came to working outdoors. Ekushey Padak awardee Professor Farida Zaman remembers how frightened she felt if she needed to go outside, for instance in Ramna Park, for outdoor projects. "A crowd would often gather, and people would make snarky comments. I would have to leave soon," she said about the circumstances in the early 70s. Nowadays, though people are more accustomed to seeing female artists at work, there is still a lack of security, added the artist. Though she did not face any opposition from her family in pursuing a career in the arts, she feels that a female artist needs to create her own space and find time, amidst her multiple responsibilities, to establish her work.

Like her teacher Professor Farida, Shameem Subrana, the owner of Gallery Twenty One, had full support from her progressive family. She is the first female artist to own and run a gallery in Dhaka. She, however, emphasised on the importance of emotional and financial support as well as help with child care for an artist to be successful. Shameem noted that art is often wrongly viewed as a hobby rather than a serious endeavour, especially when women pursue it. "The double burden of running a household and creating art can weigh women down. If they don't have support from their families, they often end up giving up on their careers and passions as artists to become mothers and wives and caretakers of the elderly. It is often framed as a 'choice' but it is really forced choice, in most cases," she told The Daily Star.

The struggle for Kanak Chanpa Chakma was initially intensified by people's prejudices against the indigenous community. She shared how she faced stereotypical questions from many of her classmates, when she joined the Fine Arts Faculty in the 80s, as its first indigenous female student. "But the real fight began when I completed my degree and entered the professional world," she said. "I often had to hear that women's artworks are 'feminine'. I still do not understand what they meant by that. A woman, too, has to work as much as a man, perhaps even more so to get recognised for her work."

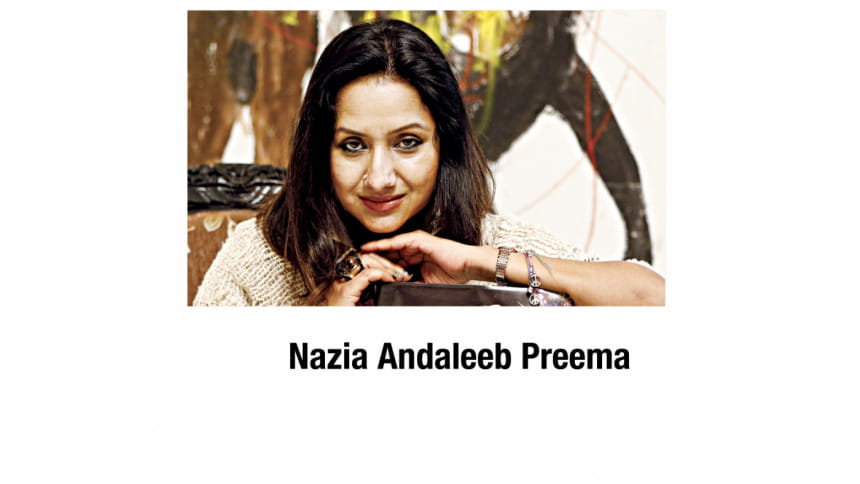

On the other hand, Nazia Andaleeb Preema presents herself as a feminist, as 'feminism is humanism' for her. The artist, whose work often focuses on the political, diverse, liberal, plural and equal woman, feels that works of male and female artists are not always evaluated using the same standards. "Besides, it becomes difficult to network when you are a woman," she said. However, she believes that the struggles that women face are often blessings in disguise.

Dinar Sultana Putul, a more recent name in Bangladesh's art scene, elaborated on Preema's point. "Nowadays, art is not bound within the canvas. Subsequently, women artists are able to express their true feelings. Their works involve more sensitivity than those of the male artists," she said. Stating that she has never felt discrimination in this field, Putul opined that female artists are doing much better in contemporary art, compared to the males.

Perhaps things are changing compared to Zeenat's time. Today, 383 young women are studying to be professional artists in the same institution, where Zeenat started her journey with only three other female classmates.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments