October (1927): A Historical and Visual Retromania

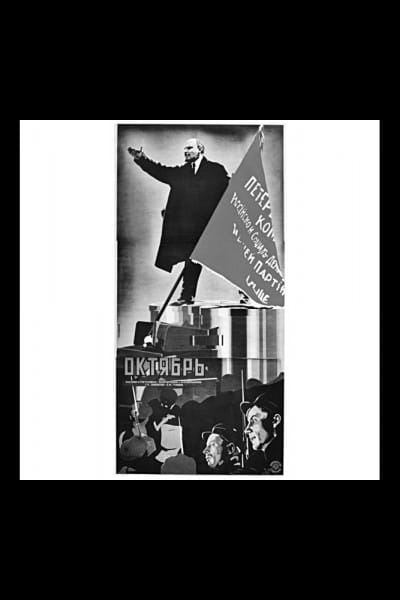

Let's imagine some frames from the 80s or 90s - a small group of activists watching a film in their semi-dark Communist party office; some film students viewing a movie projected on their classroom wall; and a few bibliophiles who had just read John Reed's Ten Days that Shook the World eagerly discussing Sergei Eisenstein's trilogy on Russian revolution. Such frames evoke the way people once viewed Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov's Russian film October (1927). On the centenary of Bolshevik Revolution, both the mass movement and the film equally demonstrate retromania for a time when the working class and the peasants of Russia had shaken the world, demonstrating in the process the collective power of the mass.

Commissioned to make a film on the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution (1917), Eisenstein launched his herculean visual enterprise October: Ten Days that Shook the World (the subtitle was added after John Reed's novel) in epic style. In the path of his cinematic guru D. W. Griffith and his ideological mentor Karl Marx, Eisenstein created a new mode of editing involving the juxtaposition of images and ideas which has subsequently been theorised as montage. Influenced by Marxism, he went into putting side by side pre-revolutionary and revolutionary dialectics through a train of scenes in monochrome. Eisenstein also visually delineated the subtle tension within the revolutionaries – the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks—brilliantly in the process.

Eisenstein, a devoted chronicler of Russian revolution, left his pioneering signature of intellectual montage—a form of film editing where sequenced scenes are presented in quick succession to depict certain ideas—in films like Strike (1924), Battleship Potemkin (1925), October (1927), and Alexander Nevsky (1938). His innovative technique of visual editing articulated the revolutionary events artistically. October, a film with no spoken dialogue, lets spectators experience inner intrigues and the revolution's climax through the sonic complements of Russian composer Dimitri Shostakovich.

A recreation of the colossal historical events of the Soviet Bolshevik revolution, October spans six crucial months of the post-February-Revolution era till the October Revolution. Co-directed by Grigori Aleksandrov, this film utilized a huge army of crew and cast members who worked for about six months in Leningrad (previously Petrograd) to shoot this film. Referring to the shooting as "life in the fourth dimension", Eisenstein said, "Sometimes we filmed for sixty hours without respite … We slept on cannon carriages, on the pedestals of monuments, … in the assembly hall at Smolny, by the gates of the Winter Palace, on the steps of the palace's Jordan Staircase, in automobiles (the best sleep!) … The rest of the time we filmed. Altogether, we shot about a thousand scenes."

Filmed in documentary style, the weaving of the tensions and events of a historical moment has never ceased to awe cineastes and academics. Indeed, the last scene of the storming of the Winter Palace by the Bolsheviks can easily be viewed as a real-life event by modern audiences. The simulative mise-en-scène of thousands of casts in one scene is perhaps one of the most momentous cinematic moments of modern filmmaking, along with the Odessa Steps scene of Battleship Potemkin.

Despite its strict state regulation regarding art and culture, the Stalin administration (thankfully!) didn't interfere with Eisenstein's filmmaking, although he was asked to expurgate reference to Trotsky. Eisenstein, though a leftist sympathisers, delineated the revolutionary character of Lenin deftly and contrasted the subtle tension between the Bolsheviks and the representatives of Provisional government followed by dismantling of the Tsar's monument adroitly.

October's treatment of the scenes depicting the social reality of post-Tsarist Russia under the Provincial Government resounds with Eisenstein's Marxist understanding of the unrest during interim government. In spectacular montage, we view juxtaposition of different religious deities followed by the title-card "...and the country" accompanied by the tilted head of Tsar's statue. Such images reveal the politico-religious exploitation by the old regime and the universality of religious conservatism.

Eisenstein perfected his signature style while working for Proletkult Theatre. His editing style has been dubbed as a "montage of attractions" in which seemingly arbitrarily chosen images are juxtaposed. In reality, though, they have been put in non-chronological order to intensify the psychological impact on the audience. This technique, indeed, pervades his cinematography. His shift to cinema from theatre can be justified by the potential mass impact of the cinema in educating the general people. Such 'mass-epical' depiction of popular movement accompanied by cinematic hermeneutics has made October a key-text of Eisenstein Studies, analyses by research groups and study sessions in museums and film schools. His involvement with the Red Army and Popular Theatre and his own individual position as a Jew in Russian society under Stalin in post-Revolution period no doubt shaped his ideological character

Though the film had evoked contradictory responses once (no doubt because of its then new techniques of montage and cross cutting), October is now considered to be a landmark film of the silent era. Its visualization of the revolution echoed across the globe then and has by now taken the film to mytho-poetic heights. The revolutionary zeal of the film has had universal appeal. October voices against all oppressive states and all sorts of exploitation. The message of the film reminds one of the popular ideological slogan of the French Revolution (1789) "Liberty, Equality and Fraternity." Employing their mastery of film making to spectacular effect, Eisenstein and Aleksandrov created a unique grand narrative in film. And the legacy of their work seems to be reverberating "la luta continua"!

Kazi Ashraf Uddin is Assistant Professor of English at Jahangir Nagar University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments