Imagining Africa in Bengali fiction and verse

Growing up in our part of the world in the second half of the 20th century, and fed on a diet of popular fiction, comic books, TV "nature" documentaries and Hollywood films, who amongst us did not view Africa as a place of abundant wildlife, spectacular landscapes and adventures and people with exotic dresses and seemingly strange customs? Growing older and becoming addicted to more serious fiction, a few of us perhaps abandoned the romantic images digested via our reading earlier to reconsider it as a continent full of "darkness" and the lingering aftereffects of colonial excesses. Those of us feeding on a diet of international news in the 1970s may even recall at this point Idi Amin's wrongdoings in news reports, having as well met or heard about people of South Asian origins in Africa forced to abandon their workplaces because of dictators like him.

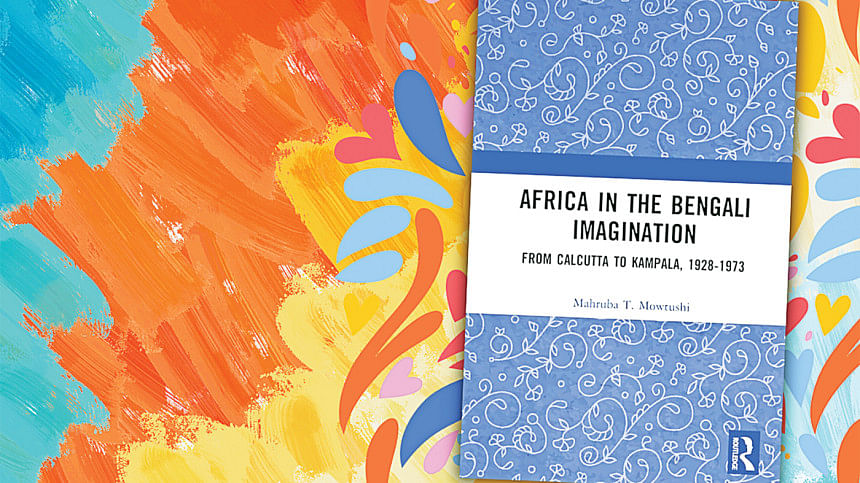

In other words, images of Africa may have struck us variedly at different stages of our life, even though we marginalised such images in our mind as the years went by. Reading Africa in the Bengali Imagination, Mahruba T Mowtushi's illuminating work on Bengalis who had written about Africa imaginatively, one is struck by the swerves Bengali writing about the continent took over time. Mowtushi charts a course in her book of criticism that takes us from imagined and exoticised narratives about the continent at one stage to works based on first-hand experiences and close encounters in Africa of the thought-provoking and affective kind.

Mowtushi's work is based on a childhood lived in North Africa that eventually led her to a scholarly quest. In the early 1990s she had spent some years in Algeria with her parents because of her diplomat father, and had gone to a school in Algiers, where she became intimate with a few Nigerians and Kenyans. These years and the nostalgia that they induced in her when she went back to Dhaka made her feel that she had to read African literature in English with "passion", albeit all by herself, aware that her Bangladeshi friends took a dim view of the continent and Africans, fed as they had been on negative images and racial stereotypes. Consequently, she immersed herself in whatever she could find of Bengali writing about Africa.

Mowtushi's book is thus an outcome not merely of nostalgia about a continent and places she had lived in earlier, but also a sustained critical attempt to trace the evolution of Bengali attitudes to parts of the continent over the 20th century, particularly the stretch of land in East Africa that includes Kenya and Uganda. She stresses how in the early 20th century the Bengali "imagination" had "pandered to Western stereotypes of Africa", fictionalising it from subcontinental perches with a false sense of superiority, forgetting perennial mutually beneficial civilisational ties between peoples of the Indian subcontinent and Africans living on the other side of the Indian Ocean. Using something like EM Forster's "only connect" as her leitmotif, she concentrates on five writers, the first three of whom—the novelist Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhay; the children's writer and essayist, Hemendra Kumar Roy; and the poet-philosopher, Rabindranath Tagore—write entirely imaginatively in their depiction of the continent and its people, while the last two—the playwright Ganesh Bagchi and the poet Rajat Neogy—put their imaginations to work in articulating their felt responses to Africa and life there either on the basis of their diasporic experiences and desire for belonging, or anguish about being ultimately uprooted from the land and its peoples.

With the obvious exception of Rabindranath Tagore, Bhibutibhushan Bandyopadhay is the most famous of the five Bengali writers Mowtushi chose for her critical voyage into the role Africa has played in the Bengali imagination. Bhibutibhushan's novel Chander Pahara (1937) is about its protagonists' travails in East Africa where he is part of a workforce doing construction work for the Ugandan Railway; however, he abandons such work for diamond exploration. Readers/viewers of Panther Panchali (1929), the classic Bhibutibhushan novel/Satyajit Ray film will understand why a Bengali might have felt the need to leave his homeland because of issues "relating to land, migration and loss of indigenous capital" consequent to colonial debilitation, and why the novelist had chosen a less known work to reimagine his protagonist Shankar breaking the mould used to cast Bengalis as effeminate, passive people, inclined to clerical work, and to project him as enterprising and willing to strive for financial success in Africa. Using his English education and knowledge of English adventure novels confidently, Shankar ventures into a continent where he can make a distinctive contribution, utilising his intellectual superiority. He, however, finds the task far more challenging that he had anticipated and even intimidating at times because of many obstacles in his way. The end results, however, are positive, for he will return to Bengal feeling he can start life anew in it. Mowtushi notes that the novelist has Shankar come back in 1910 with "renewed love and devotion for Bengal" at a time when nationalist fervour had gripped Hindu Bengalis.

Mowtushi chooses to focus on Hemendra Kumar's Abar Jakher Dhan (Dev Sahitya Kutir Pvt Ltd, 2017) next. This is another narrative about empowering the self through adventurous encounters in Africa. Mowtushi views Hemendra as deploying a "spatial symbolism" and "developing a "desh-city-bidesh triad". Escaping the regulated life of Calcutta for treasure hunting in Africa, and eschewing the soft but constricting options of "bhadrolok" and "babu" culture, Hemendra's protagonist Bimal opts to pursue adventures in the African wilderness, hoping to tame or dispose of the threatening wild creatures of the continent he comes across. Bimal's adventures, Mowtushi observes, is his "manly rites of passage", but though Hemendra is not unwilling to stereotype Africans and demean them and their lifestyles in places, he is also forthright in critiquing Calcutta life and Calcuttians. Hemedra's fictional intent, she concludes, is to inspire a new generation of its citizens "to establish a virile and wholesome relationship with the nation, as opposed to the effete babuyana of the bhadrolok".

At the heart of Mahruba Mowtushi's book is a chapter featuring Rabindranath Tagore's 1937 poem "Africa". Written a few years before his anguished response to the way the world was caught up in a maelstrom created by rampant nationalism, imperialism, and fascism, Rabindranath sets out in the English poem to show, as he himself explained in a letter, "how an Indian poet feels about the despoliation of a whole continent in the name of civilization." This would entail moving away from the romanticising perspectives adopted by Bhibutibhushan and Hemendra, and adopting a viewpoint that would affirm "anti-colonial solidarity" and revive civilisational ties between India and Africa strained and marginalised by colonial excesses and disinformation. The need for Europeans, Tagore felt, is to recognise the havoc they had wrought on the continent, seek forgiveness for what they had done, and embark on "reparation and rehabilitation."

Mowtushi's final chapters deal with two Bengali writers, who, unlike Bhibutibhushan, Hemendra and even Rabindranath, would be writing about the continent and Indians in Africa on the basis not merely on what they had read or heard about the continent, but on their lived experiences. The first of them, Ganesh Bagchi, had left Calcutta for Kampala in 1948, hoping to root himself in the place professionally. To him, unlike Bhibutibhushan and Hemendra, this is no "dark" continent; he fully desires to belong to it. Bagchi's plays and memoirs thus reflect his intention to find in his part of Africa a viable alternative to Bengal in the 1940s, which was disintegrating in all kinds of ways as well as reeling from the impact of the 1943 famine. His initial plays, however, seem to be inspired by his critique of the "oppressive, bureaucratic system" hampering growth in the part of Africa he had wanted to make his own, for such colonial leftovers were stifling and stunting its people and deterring men like Bagchi seeking alternatives to what they had experienced in India. He even wrote a play to promote "multi-racial existence" but reality seemed to show him ultimately that this was not feasible. Failing thus to belong to a land where he was unable to endorse what was going on, and where migration did not bring the kind of rehabilitation he had envisaged, he leaves the continent with "unrequited longing".

Bengali expatriates in Africa like Bagchi are thus often subjected to "multiple displacements and replacements", experiences that also mark the life and works of the final subject of Moutushi's book on Africa and Bengali imaginative writing about it—the poet Rajat Neogy. Bengali racially but Ugandan by birth, cosmopolitan by upbringing and nonconformist by inclination, when still in his early 20s, Neogy had launched in 1961 an avant garde journal called Transactions that not only attracted leading as well as budding African writers but also became an outlet for his experimental prose poems. But the Uganda he began his writing career in soon became prey to dictators exploiting nationalist feelings. Neogy's poems then veer towards pessimism and surrealism, thereby indicating a poet inhabiting nowhereland and articulating despair. His poems and journal proved too provocative for Uganda's rulers; he soon ends up in prison and ultimately leaves the country, heading first for Ghana, but then opting for the USA. Distraught by what was happening in his part of Africa but also by the events of 1971 in Bangladesh, he seemed to have wanted to assume a Bangladeshi persona as well, writing poems about his bewilderment at events there and even embracing Islam, as if to identify himself with the majority of the people of the land. And thus it was that he became "a Muslim Bengali émigré seeking rehabilitation in the United States"!

Mowtushi Mahruba's Africa in the Bengali Imagination: from Calcutta to Kampala, 1928-73 is a distinctive and pioneering work on the way the continent led to creative writing in English as well as Bengali over the decades. Solidly researched, and revealing her combing Bengali writing and focusing not only celebrated Bengali writers but also almost forgotten ones, it is a testament of her wanting to identify imaginatively with a world and people she had valued but had been distanced from by time and circumstances. What is also impressive about the book is the way its chapters have been arranged and the overall scholarship and imaginative leaps she has taken to introduce us to writers, themes and patches of history we would otherwise overlook. Moreover, she writes lucidly and with assurance as well as feeling. The intricate way she threads her narrative is particularly impressive. This is a book that deserves to be read for all these reasons.

Fakrul Alam has retired as Professor of English at the University of Dhaka but continues to teach there and at East West University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments