A priceless fictional heirloom

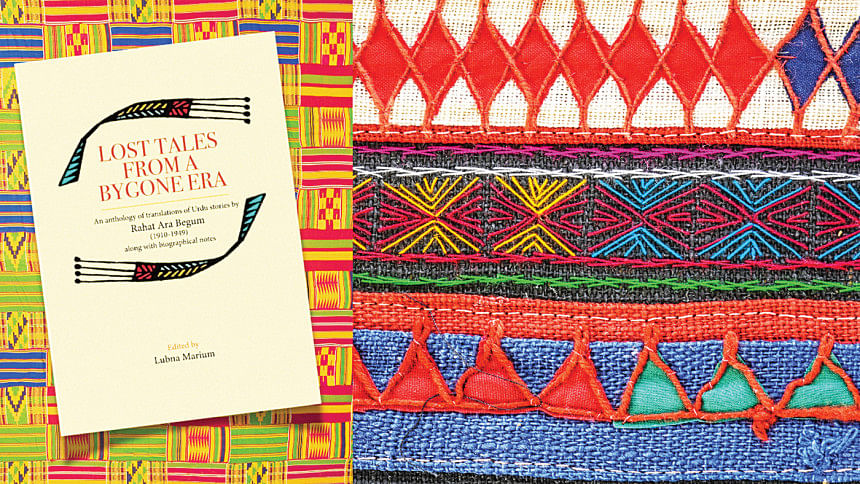

There are any number of ways one can approach Rahat Ara Begum's collection of short stories, Lost Tales from a Bygone Era: An Anthology of Translation of Urdu Stories, assembled, contextualised and published in this book by her loving grandchildren and their siblings. One can view their work as a recovery of not only a female ancestor's works; one can also feel in reading it their delight in coming across her considerable fictional talent and preserving it for posterity. The realisation that their grandmother had used the short story form with considerable skill and sensitivity to depict the lives of women and their loved ones of "a bygone era" is something her descendants can justifiably take pride in.

Another way of looking at the stories anthologised in the volume is to stress their artistry, for Rahat Ara's ability to bring us close to diverse aspects of men-women relationships in the pre-partition era fictionally is an achievement that can in no way be underestimated. Indeed, when one thinks of the way most Muslim upper-class women were made to spend their lives in the innermost parts of houses and cope with all sorts of restrictions placed on their movements routinely then, her coverage of these areas and of their occupants artistically in her short stories featuring them appears even more admirable.

I am reminded a bit by the last of these questions of A. S. Byatt's 1990 Booker-prize winning Possession (Random House), which at least in part depicts the excitement and thrills experienced by the fictional descendants of the woman poet at the center of the novel when they discover her literary "remains".

A third way of approaching these works, however, is to not be influenced solely by considerations dependent on cultural and social history to arrive at the real estimate of Rahat Ara's writing skills. In other words, one can try to assess her writerly abilities: how good was she as a chronicler of women's lives in her era and what skills and techniques did she deploy in her writing to portray her characters and delve into their minds and the intricacies of their relationships?

Finally, a point that can be dealt with relates to the genesis of the book. How did the "lost tales" come into public view seven decades or so after they were written and after the writer herself had passed away?

I am reminded a bit by the last of these questions of A. S. Byatt's 1990 Booker-prize winning Possession (Random House), which at least in part depicts the excitement and thrills experienced by the fictional descendants of the woman poet at the center of the novel when they discover her literary "remains". We are made to believe that she had all but disappeared from the English literary landscape and would have perhaps been only a footnote in literary history, if she and her manuscript not been accidentally rediscovered and treated as an extraordinary inheritance by a pair of young academics, one of whom is a close relative "possessed" by the desire to retrieve a lost reputation. The thrills of holding in hand a lost but priceless family heirloom is something Byatt makes palpable in her novel.

From the prefatory material of Lost Tales from a Bygone Era we learn that the stories were originally written in Urdu and published either in Kolkata or in Lahore between 1939 and 1948. We also gather from the introduction the collective excitement that spurred the grandchildren on to search for her works in libraries in Lahore, Hyderabad and Kolkata as well as the University of Dhaka. As Lubna Marium, the editor of the volume, points out in her Introduction: their grandmother's work and Rahat Ara herself had been almost "erased from public memory". This was something that drove her and her sister Naila Khan, "the Project Coordinator", to "retrieve Rahat's publications and reprint them in the original or in translations." And it was thus that they managed to get the stories translated by Neeman Sobhan, Rukshana Rahim Choudhury, and Aamer Hossein. Collectively, they as well as the other grandchildren and great grandchildren had felt that it was "certainly time to bring out into the open and celebrate her unusual but creative life".

To turn now to the nine stories of Lost Tales from a Bygone Era, six of them deal with Muslim characters and three with Hindu ones. In other words, Rahat's focus extends across religious boundaries, something surely remarkable in pre-partition Bengal. Spatially, too, there is variety, for we have stories set in villages as well as cities. The social standing of the characters, moreover, reveal the range of her interests, for they include people coping with poverty on the one hand, and financially well-off people, or even aristocratic ones, on the other. But almost all the stories deal with situations arising from love or desire, and the barriers in the way of lovers preventing them from uniting with their loved ones, or the hurdles that have to be crossed to live happily. As in life, Rahat depicts tales with endings depicting union and fulfillment in addition to ones that have tragic or disturbing outcomes. Not surprisingly for a woman writer of that period, Rahat depicts the vulnerability of women in quite a few of these stories, and the stereotypes about female duties and conduct and the boundaries they are confronted with.

Only on a few occasions does Rahat signpost a moral from the conflicting situations she portrays in most of her stories. A moral that can be considered representative of her position on love and marriage is what we come across in the following lines from "The Confession": "Love and trust are the only two things that can transform an individual's life into paradise." Not unsurprisingly perhaps for a woman writer of her time, Rahat also has a point to make implicitly in some of the stories that is used almost like a refrain in "The Young Student": "A man can love many women at the same time. His heart probably has compartments where he has to keep the love of many women. But a woman loves only once in her lifetime." And implicit in quite a few of the stories is the one encapsulated in the title of the story: "Azadi" or "Freedom": women would like to come out of confinement if they could do so. But the story ends by showing how a predatory man attempts to abuse her for daring to do such a thing, although her husband will continue to believe in her!

On the whole, Rahat Ara prefers to show and not tell. Thus readers will more often than not have to draw the moral or the point being made in a story through the thrust of the narrative and on their own. This never poses a problem to the reader though since her story-telling method is simple and the pace of the narratives gentle. Almost always, the reader is carried along by the plot and assisted by the narrative techniques she uses. The events depicted seem natural and the setting is portrayed economically. Because the translations are very readable and the book neatly produced, readers will surely be able to go through the nine stories on their own easily whenever they want to.

One can only hope that more such efforts will be made by Rahat Ara's descendants to rediscover other manuscripts she has left behind in addition to publishing some of the other collections of stories they already have in their possession. Present and future readers can then relive the past and come across the stories of people whose memories may have dimmed but whose lives still can be revived fictionally for pleasure as well as for guidance, and for coming to know more about our past social and cultural history.

Fakrul Alam has retired as Professor of English from the University of Dhaka and is now Adjunct Faculty and Adviser, Department of English at East West University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments