Higher growth a must to raise income status

The recent reclassification of Bangladesh to a lower middle income country (LMIC) has been a highlight in its long voyage towards economic development. But what does it really imply? Is it reason enough for us to relax for the time being?

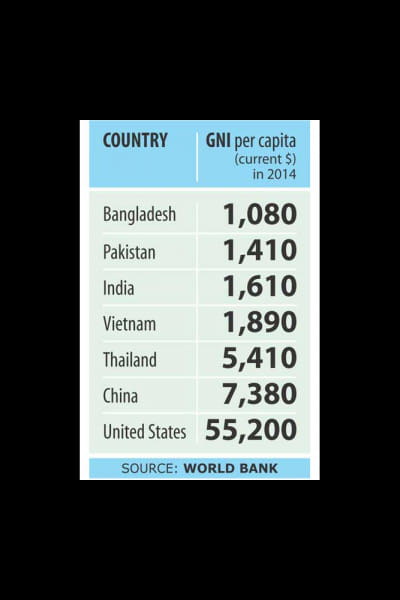

In order to progress to an LMIC, a country's gross national income (GNI) per head needs to be higher than $1,045. Bangladesh's GNI in 2014 stood at 1,080 and as such it was promoted to an LMIC.

This is, no doubt, the fruits of the country's resilience over the years. We know that Bangladesh has been able to maintain an economic growth rate of 6 percent and above despite the dreadful global economic slumps.

For Bangladesh, joining the league of LMICs is just the first step towards further economic growth. The country now envisages becoming an upper middle income country (UMIC) for which it needs to churn out an annual GNI per head of at least $4,126.

Simple calculations can tell us that if the Bangladesh economy can grow by 8 percent annually, this can be achieved by the early 2030s. However, at the current growth rates of 6 percent, the country may not be able to achieve its target even in the next 30 years.

It is important to note that Bangladesh has climbed the minimum threshold level by a narrow margin to get promoted as an LMIC and still is at the bottom of that echelon. The country still has not been able to achieve its growth rate target of 7 percent.

East Asian economies have shown that transformational changes in the economy came about when these countries were growing at a rate of 7 percent or higher annually.

For Bangladesh, achieving the growth rates of 7-8 percent per year would require going the extra mile. Let us look at the investment scenario in Bangladesh.

Investment as a proportion of GDP has been hovering around 28 percent for the last five years.

Though public investment has been on the rise in recent years, private investment (which is instrumental in attaining higher growth rates) seems to be more or less static.

In order to achieve growth rate of 8 percent, investment to GDP ratio needs to increase from 29 percent to 35 percent.

Turning to foreign direct investment (FDI), Bangladesh managed to rake in only $1.5 billion in 2013 as compared to India ($28 billion), Vietnam ($9 billion), Malaysia ($11.5 billion), Indonesia ($23 billion), and China ($347 billion).

Despite having advantages of cheap labour and large market size, investment is arrested by problems in enforcing contracts, getting electricity and registering property (Doing Business Report, 2015).

Other major barriers to investment include a lack of energy, inadequate infrastructure and political instability.

Growth has been stalled by insufficient energy. Investment is required in the energy sector to keep up with the rising demand. All these factors can hinder economic growth and discourage foreign investments.

Exports have hugely contributed to higher growth rates over the decades. However, the country's export basket is largely concentrated on garments that made up 82 percent of the total exports in fiscal 2015.

This makes the industry vulnerable to shocks that may stem from domestic inadequacies and rival countries. A way to lower dependency on garments and to increase exports is through adding new products into the export basket and finding new markets.

Also the protection system that currently exists in Bangladesh creates an anti-export bias which makes domestically produced import competing goods more profitable to sell in the country rather than exporting.

Investment in human capital needs to be increased. Government expenditure allocation for education is only 1.8 percent of GDP compared to India (3.8 percent), Indonesia (3.6 percent) and Vietnam (6.3 percent).

The problems of dropout rates in primary (21.4 percent) and secondary education (44.4 percent) still persist. Moreover, public spending on health is only 0.7 percent of GDP.

Remittances have also been a major contributor to the economy, generating a total of $15 billion in fiscal 2015. Increasing education of migrants and improving their skills can help raise the average remittance per worker.

Promotion to LMIC status can also lead Bangladesh to lose the advantages that it used to get as a low income country. For instance, the terms and conditions may get stricter for getting funds from development agencies.

On the other hand, the country can now take out loans relatively easily from international financial institutions due to its higher credibility.

It is also important to remember that becoming an LMIC does not necessarily mean greater income equality. We must note that a quarter of the population still remains below the national poverty line.

For Bangladesh, growth should be sustainable and inclusive to achieve its targets.

The writer is the head of research at The Daily Star and can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments