Can merger be panacea for banking sector’s ills?

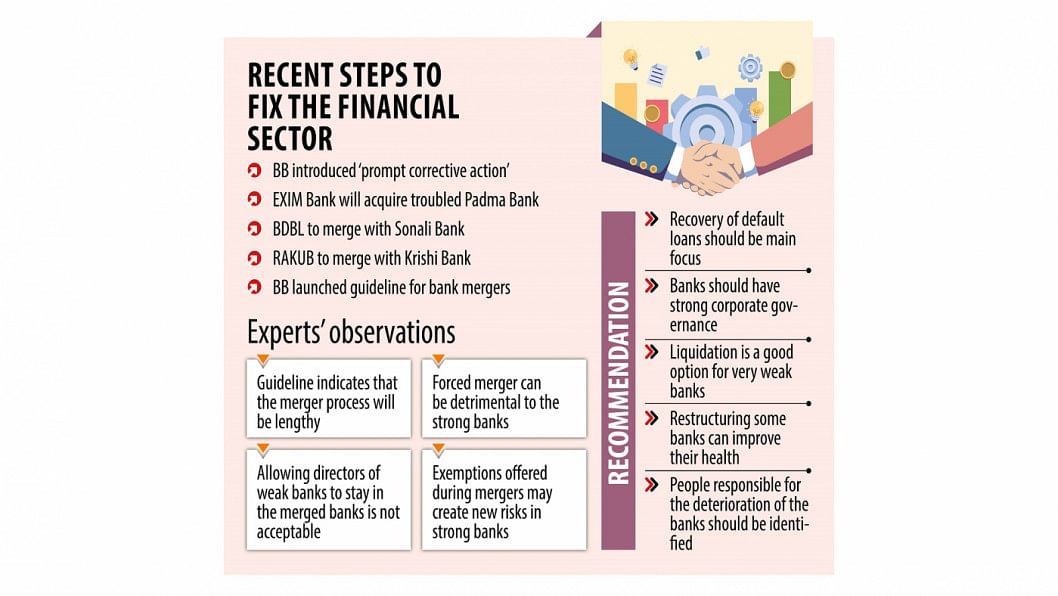

The merger guideline for banks and financial institutions is being hailed as a major step towards fixing the problem in the financial sector, which has been weighed down by massive default loans and weak corporate governance.

However, risks remain, according to experts and bankers.

For example, if the directors of weak banks are allowed to be included in the acquiring lenders, the same problems that have caused the merged entity to sink in the first place may surface in the acquirer.

Furthermore, forced mergers can lead the health of strong institutions to deteriorate and easing rules for the involuntary process will create new risks among the stronger ones, they said.

The central bank went for the corrective measures for the financial sector in line with the recommendations made by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) under its $4.7 billion loan programme.

"However, the guideline is not giving the full comfort of seeing a reduction of risks in the financial sector. Moreover, it has kept doors open which may create new risks," said Zahid Hussain, a former lead economist of the World Bank's Dhaka office.

Implementing mergers might take long if institutions don't like to acquire the bad lenders willingly.

The guideline comes last week after the BB issued the Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) framework in December to give a procedural direction for mergers and acquisitions amidst the deteriorating financial condition of some banks and financial institutions. The PCA will come into effect from March 2025.

In the light of PCA, the central bank will identify banks in four categories based on loans, profits and other indicators. After identifying them, the BB will direct weak lenders to improve their performances in 12 months. If they can't bring about any positive changes within the stipulated time, the central bank will seek bids from buyers.

If none comes forward willingly, the BB may force stronger banks to acquire them.

"It's a long process," said Hussain.

"The guideline indicates that there is no option for liquidation, why not? Any forced amalgamation would be risky."

If the central bank compels a strong lender to absorb another financial institution, it may give some policy support in liquidity calculation and in some other prudential regulations.

Some banks may acquire another to enjoy the exemption only. "So, this compromise will create new systematic risks in the banking sector," he said.

The guideline gives an indication that the non-performing loans (NPLs) of weak banks may be bought by an asset management company to be financed by the government. This means the taxpayers will carry the ultimate burden of the default loans.

Similarly, if the central bank subscribes to the bonds as cited in the case of forced merger, this will mean printing of the money by the BB to help run default-hit banks.

"These will create many other problems in the sector," Hussain said.

"On top of that, the defaulters will not be punished. Similarly, directors will not face any music for their failure to keep their institutions on track."

The guideline said managing directors, additional managing directors, and deputy managing directors of the weak banks can be appointed if the board of the acquiring banks agrees.

"So, the fear of being infected by the irregularities of weak institutions will remain among strong banks."

Syed Mahbubur Rahman, managing director of Mutual Trust Bank, welcomed the BB's merger move, calling it a timely initiative.

"The guideline is to strengthen the banking sector, protect depositors, and ensure a smooth transition during mergers."

He, however, says the success of such mergers hinges on ensuring transparency and accountability throughout the process.

According to Mashrur Arefin, managing director of City Bank, the most encouraging part of the guideline is that after the legal merger, there will be a three-year period to restructure the weak bank before consolidating the balance sheets of the two entities.

"The central bank has taken a commendable decision."

Nonetheless, the provision allowing the bad bank's directors to return to the new entity after a five-year hiatus seems impractical, even though it stipulates that their loans must remain fully regular during this period, with no loan rescheduling or restructuring permitted, he said.

"Such legal provision could potentially reward those responsible for past misdeeds, contradicting the culture of accountability that the central bank aims to establish."

Another concern is the three-year job security guaranteed for the staff of the bad banks, Arefin said.

"This guarantee is likely to result in two distinct performance management processes and cultures within the staff of the two merging banks, complicating the integration of culture and personnel to a large degree."

Since the merger involves many parties, a direction from the Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission may be needed, said Mohammad Ali, managing director of Pubali Bank.

All strong banks have correspondence with foreign banks for the opening of letters of credit and some other businesses. If a merger weakens the capital situation of banks and the central bank eases the capital adequacy ratio for them, it remains to be seen what the reaction of the corresponding banks will be, he said.

"These issues should be analysed."

The merger will alone solve the problem of the banking sector is a simplistic concept, said MK Mujeri, a former chief economist of the central bank.

"The root cause of the existing problem of the banking sector is the spike in bad loans and a culture of defaulting intentionally among powerful people. Therefore, the government needs to have a strong mindset to reduce willful default loans, remove policy weaknesses, and implement the corrected rules and regulations."

"The merger can be a step towards restoring discipline in the financial sector. However, it is not the ultimate solution."

He thinks a merger can improve good governance and administrative, and corporate culture. On the other hand, it can weaken the strong banks since the number of sound financial institutions in Bangladesh is low.

The World Bank also cautioned that forcing bank mergers without assessing asset quality could be counterproductive and rapid implementation of mergers should be done with care.

"The central bank needs to identify the people responsible for bringing the sector to the current sorry state," said a top official of a bank.

"The directors of the poor banks should never be allowed to sit on the buyer's board. Otherwise, stronger banks may face problems in fixing the accumulated problems of weak banks."

The official said the overhead costs of the weak banks are already high, which might deter strong banks from acquiring the former.

"If weak banks are forced to merge with stronger ones, it may impact stronger banks," said Emranul Huq managing director of Dhaka Bank.

He thinks liquidation can be an option for weak banks.

For some banks, restructuring by including government, experts and corporates can be a good option. For instance, once a poor bank, Eastern Bank was restructured and it is now one of the top banks in Bangladesh.

World Bank's Hussain said the main goal of the merger is removing the risks of the financial sector, so the recovery of the NPLs should be the key focus.

"The efforts to end corporate misgovernance should be beefed up."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments