BTRC may face investment arbitration soon

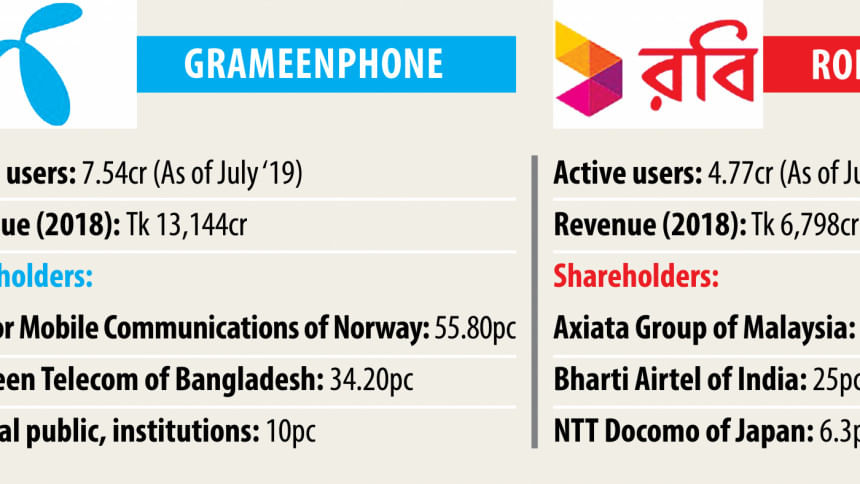

Robi is a subsidiary of Kuala Lumpur-based Axiata Group Berhad. Other significant shareholders in Robi include Bharti Airtel International (Singapore) Pte Ltd and NTT DOCOMO Inc, respectively based in Singapore and Japan.

On the other hand, Telenor Mobile Communications AS (TMC) holds the majority shares in Grameenphone. TMC, which is an indirectly wholly-owned subsidiary of Telenor ASA, is listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange and owns 55.80 percent of the entire stock of Grameenphone. Among other shareholders of the operator, Grameen Telecom holds 34.20 percent shares and the rest 10 percent shareholding includes general public and other institutions.

The BTRC's decision to serve the notices on Robi and Grameenphone did not come about out of the blue. In a previous attempt to realise the dues, the commission restricted the internet bandwidth capacity of Robi and Grameenphone by 15 percent and 30 percent respectively. Later, although the BTRC restored the bandwidth capacity on the grounds of inconveniences faced by the customers, it decided to withhold all kinds of approval to Robi and Grameenphone with regard to rolling out new package or service as well as import of network equipment in a bid to compel them to pay off the dues.

In this backdrop, cancellation of licence of Robi and Grameenphone will allow their respective foreign investors to espouse investment claims at international forum. Since Bangladesh has concluded bilateral investment treaties (BIT) with Malaysia, Singapore and Japan, it will not be much problematic for the foreign shareholders in Robi to bring investment disputes before the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) tribunal.

On the other hand, Bangladesh has not concluded any BIT with Norway. Therefore, the possibility of bringing an investment dispute by TMC or Telenor ASA will much depend on their corporate structures. Apart from Telenor Group, there are chances that other foreign shareholders in Grameenphone may avail of ICSID arbitration if Bangladesh has already concluded BIT with the country of which any such shareholder is a national.

One should take note of the fact that both Robi and Grameenphone have proposed to submit their respective disputes to arbitration under the Arbitration Act, 2001, but the which BTRC has turned down on the excuse that the Telecommunication Act, 2001 does not envisage any scope for such arbitration. However, it must be admitted that consent of the BTRC to arbitration in this regard would have been beneficial to everyone concerned. Not only would it provide an opportunity to solve the disputes domestically in time and cost-effective manner, but it would also obviate the possibility on the part of the BTRC to get entangled in international litigations.

At this point, one cannot fail to notice that the BTRC's actions to realise the claimed amounts from Robi and Grameenphone are not in compliance with the Telecommunication Act, 2001. For instance, section 26 of the Act provides that the Public Demand Recovery Act, 1913 could be availed of in order to recover dues owed to the BTRC. Thus, the BTRC's strategy to recover dues by resorting to threat of cancellation of licence without having recourse to the Act of 1913 constitutes evasion of its legal obligation under the Telecommunication Act. If investment arbitration ultimately ensues, there is strong likelihood that these factors will count against the BTRC. Being a statutory body, the BTRC's actions will be squarely attributable to Bangladesh.

Settlement of financial disputes through arbitration is an accepted practice almost in every jurisdiction. If the BTRC would have agreed to arbitration with Robi and Grameenphone, it would ultimately contribute to the development of nascent arbitration culture in the country. Rather, the BTRC's injudicious action is helping transform financial disputes into investment disputes.

The writer is an advocate of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments