Hospital struggles to cope with Rohingya wounds

The 7-year-old Rohingya boy lies on a tattered mattress on the floor of a crowded government hospital in Bangladesh, bandages covering the spot where a bullet fired by Myanmar troops tore through his chest a week earlier.

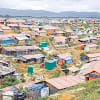

He is one of 80 Rohingya patients -- most males with gunshot wounds -- being treated at this overwhelmed medical facility in a coastal city now deluged with nearly 300,000 Rohingya Muslims who have fled a two-week surge in violence and a lifetime of persecution in neighboring Myanmar's Rakhine state. He is the youngest of six patients with gunshot wounds interviewed by The Associated Press on two recent visits.

"The soldiers just started firing he said. I saw my son on the ground," the boy's father Abu Tahir said.

In the chaos that followed they lost track of the rest of their family before Tahir carried his son across the border to safety. Now he watches as his child's ribs rise and fall in the hospital, praying that he recovers.

Sadar Hospital is the main medical facility for the Cox's Bazaar area. At the best of times it's stretched to the limit, with 20 doctors responsible for the treatment of hundreds of patients. Now it's at nearly twice its capacity and for the first time its doctors are dealing with injuries like gunshot wounds, blunt force trauma and stab wounds on a massive scale as Rohingya refugees pour in.

"We have never seen such violent injuries before," said Dr. Shaheen Abdur Rahman Choudhury, the head of the hospital.

The violence and exodus began on Aug. 25 when Rohingya insurgents attacked Myanmar police and paramilitary posts in what they said was an effort to protect their ethnic minority from persecution by security forces in the majority Buddhist country. In response, the military unleashed what it called "clearance operations" to root out the insurgents.

Accounts from refugees show the Myanmar military is also targeting civilians with shootings and wholesale burning of Rohingya villages.

Abdul Karim lies on a mat in another corner of the hospital. A mob of soldiers and Buddhist monks attacked his village in Rakhine state, set the houses on fire and sprayed the area with automatic gunfire that nearly blew off his left foot at the ankle. Another bullet wound marked his right shoulder.

The stench from his ankle made clear that Karim would lose his foot.

"We carried him on a blanket," his brother Asir Ahmed said, pointing to his shoulders to indicate how the family carried Karim and walked for days to reach Bangladesh.

In the first week of the exodus, doctors at Sadar Hospital treated 30 Rohingya for gunshot wounds. The next week they treated another 50. The hospital is now setting up a separate area for the Rohingya and expects even more in the weeks and months ahead.

Choudhury said he fears that there will be grievous injuries and deeply infected wounds as the refugees wade through filthy creeks and walk in the humid heat will no medical attention along the way. He said his hospital will need a lot more help and money if they are to cope with what lies ahead.

"This is a desperate situation," he said.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments