5 Years of influx: Rohingya return a distant dream

"We would like to go back to our ancestral home in Arakan as soon as possible and get rid of the camp life."

Khin Maung dreamt of becoming a lawyer to help the Rohingyas realise their rights in a country where they were denied citizenship.

The hope was dashed after Myanmar imposed restrictions on university education for the Rohingyas in 2012 and he had to flee to Bangladesh from the brutal military crackdown in 2017.

Five years on, he is living as a refuge in a Cox's Bazar camp, a life which he thinks is not dignified at all. Depending on others for food, clothes and shelter is not something he ever wanted.

Like many other Rohingya youths, Khin Maung is also frustrated over the lack of formal education, training or jobs in the camps. "This situation can prompt the youths to resort to illegal activities," he said.

"We would like to go back to our ancestral home in Arakan as soon as possible and put an end to the camp life," Khin, 27, told this correspondent over the phone from the Kutupalong Rohingya camp.

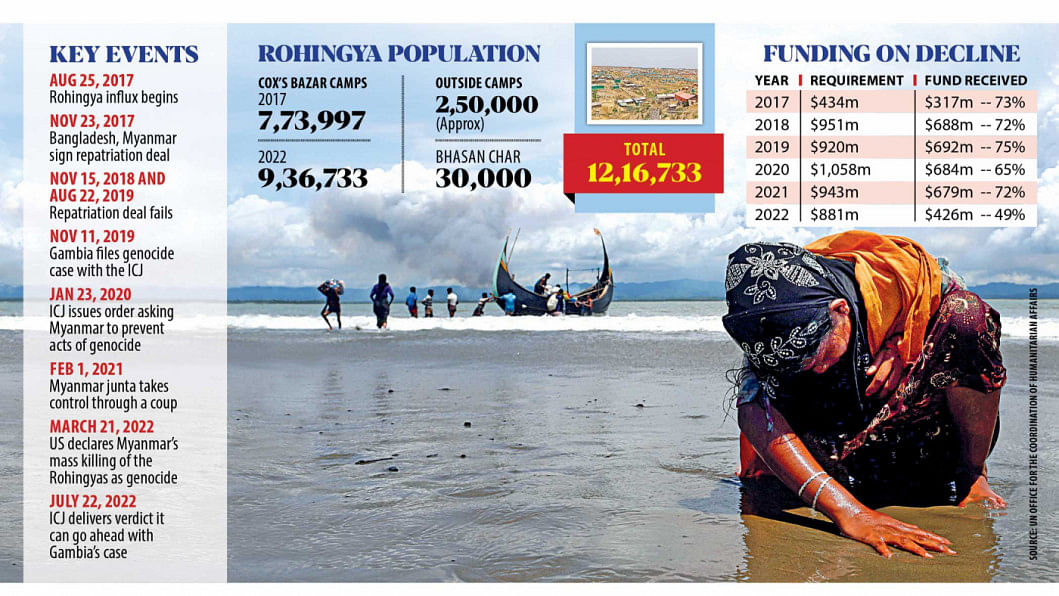

He is among about 750,000 Rohingyas who took shelter in the district in 2017, joining three lakh others who had fled earlier waves of persecution in Myanmar.

Bangladesh sheltered them on humanitarian grounds despite a myriad of challenges the country itself has to face -- poverty, unemployment and regular natural disasters that displace thousands of people every year -- while close to a million migrate for jobs abroad annually.

Things have worsened in recent times due to Covid-19 pandemic and rising inflation amid a shortage of essential commodities in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. The authorities now consider the refugee crisis no longer bearable and are calling for quick repatriation.

"We cannot continue to shelter them … we hope the repatriation will begin before the year ends," Foreign Secretary Masud Bin Momen said early this week.

But how practical is the optimism of Bangladesh? What's Myanmar's position?

According to international relations analysts, Myanmar faces higher level of pressure because of the verdict of International Court of Justice (ICJ) that it can pursue the Gambia's genocide case and the US' declaration of violence against Rohingya as genocide.

Also, Myanmar faces more pressure from the western world for restoration of democracy while the National Unity Government (NUG), formed in exile by the MPs of the Suu Kyi's National League of Democracy (NLD) following the coup in February last year, keeps lobbying various countries for support.

The NUG also announced it would grant Rohingyas equal rights as enjoyed by all citizens of Myanmar though it was the NLD rule during which the 2017 military crackdown took place.

The government in exile also promised to support the Rohingya genocide case at the ICJ.

The US, the UK, Canada and European Union also have imposed various sanctions on Myanmar military officials following the persecution of Rohingyas in 2017 and the coup in 2021, but not so much on businesses.

Prof SK Tawfique M Haque, chair at the Department of Political Science and Sociology of North South University, said Myanmar has a history of tackling sanctions for many decades, especially with unconditional support from two UNSC members -- Russia and China. The UNSC has taken no concrete actions against Myanmar since the Rohingya crisis started to unfold.

On the other hand, India and Japan, two close friends of Bangladesh, have major stakes in Myanmar and have been lenient towards the Southeast Asian country, though they want regional peace and stability and have provided humanitarian support to the Rohingyas.

Despite these realities, Bangladesh is going ahead with its attempt to start Rohingya repatriation under a deal signed with Naypyidaw in November 2017. Myanmar also has a tripartite deal with UNHCR and UNDP on improving the conditions in Rakhine State.

"We cannot continue to shelter them … we hope the repatriation will begin before the year ends,"

There is also a trilateral initiative under which China mediated between Bangladesh and Myanmar, but its two repatriation attempts totally failed -- one on November 15, 2018 and the second on August 22, 2019.

After a pause since May 2019, Dhaka and Naypyidaw began meeting in January this year. The last Joint Working Group meeting was held in June.

According to foreign ministry officials, Bangladesh handed over the names of 8.4 lakh Rohingyas to Myanmar but so far only about 42,000 have been verified.

Dhaka proposed cluster-based repatriation -- making sure that all members of a Rohingya family and all of a village are repatriated together so that they feel secure. However, the officials observed that the list of verified Rohingyas provided by Myanmar misses some members of a family.

Some of the conditions for Rohingya return have been safety, guarantee of citizenship, freedom of movement, and sending them to their ancestral homes, not to internally displaced persons (IDP) camps.

The refugees say none of these conditions exist in Arakan, a region officially known as the Rakhine State, which has been home to Rohingyas for generations.

Khin Maung said since the military coup, Myanmar people are realising what kind of persecution the Rohingya minorities have been facing for decades. However, they are still not in a position to recognise the Rohingyas as an ethnic group and guarantee equal rights.

Though the NUG is saying it would grant equal rights, there are doubts about this commitment, he said.

"More importantly, despite a ceasefire between separatist Arakan Army and Burmese military, there are clashes going on in Arakan now."

About 1.2 lakh Rohingyas are still in IDP camps since 2012 communal clash in Rakhine -- a reality which means there is no guarantee that the refugees will be sent to their homes after repatriation, he said.

Amin, a Rohingya youth in Hakimpara camp, said, "What is the point of going to a camp in Rakhine from the camp in Cox's Bazar?"

He also said Myanmar has not made any legal amendments that guarantee Rohingya citizenship.

Prof SK Tawfique M Haque said the repatriation in true sense is still a distant dream because Myanmar generals, who fundamentally control Myanmar's power, are grounded in their anti-Rohingya policy.

There is a possibility of large-scale repatriation if Myanmar military truly faces harsh actions after the verdict of ICJ and a civilian government takes office and dominate the power structure.

But that's unlikely in near future and ICJ ruling takes years. "For face-saving, Myanmar military may arrange a token repatriation in near future," said Tawfique, also director at the South Asian Institute of Policy and Governance at NSU.

Meanwhile, there is also donor fatigue on the Rohingya crisis because of other emergencies including Ukraine refugee crisis, he said.

"While we should make continuous diplomatic efforts for repatriation and mobilise foreign funding, we should also think of how the Rohingyas, especially the youths can be engaged in productive activities."

Otherwise, the Rohingyas can become a national as well as regional security threat. "International and regional players also cannot avoid the responsibility," he added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments