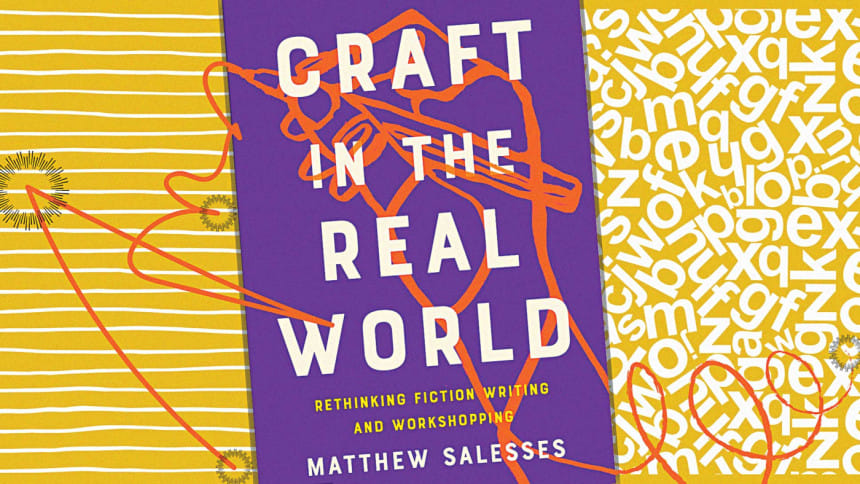

Matthew Salesses demystifies the craft of writing

Storytelling is a space in which, as writers and readers, we experience the ways of how we know the world and interact with it. Mathew Salesses's book offers a thoughtful insight into the backstage of this space. He moves beyond the place where we perform or experience writing as an artform and offers us a look at the mechanics of writing as a craft. His analysis is in-depth and the questions he poses are not surprising, yet it feels as though one hasn't thought about them as deeply before.

Matthew Salesses, a Korean-born American, is a writer and assistant professor. Presently he teaches English at Coe College and is also involved in the MFA Program at Ashland University. Salesses is the author of The Hundred-Year Flood (2015), an Amazon bestseller and his other books and chapbooks include I'm Not Saying, I'm Just Saying (2012), Different Racisms: On Stereotypes, the Individual, and Asian American Masculinity (2014), and The Last Repatriate (2011).

Craft in the Real World (Catapult Books, 2021) questions the ways in which institutions and systems that generate and uphold current models of writing as a craft mirror the power dynamics of a world that is centered around the white, cis-hetero male. As a whole, the book is a reflective guide for writers who are trying to navigate institutional spaces that have not been built with them in mind. The central themes it engages with are the relationship of culture (and a writer's positionality within culture/s) with craft, who we are writing for and why, and the ways in which power dynamics manifest in creative writing and the creative writing workshop models.

Salessess emphasizes throughout the book that craft is not just an individual act or experience of writing, but it is "the history of which kind of stories have typically held power—and for whom—so it also is the history of which stories have typically been omitted". Salesses highlights that "craft is a set of expectations" that are shaped by institutional models of workshop, readings, awards, etc. These shape the threshold with which we define which stories matter and which don't, and these "expectations are never neutral", they are representative of the population who holds power over them. In America, this means that stories (and by extension, the experiences they speak of) are viewed by the general lens of a privileged white man; negating the diversity and often unequal realities from which stories emerge. This specific power dynamic is at the heart of the book since the arguments and questions that Salesses raises is done from his position as an Asian American writer, having his writing reviewed in a system which is predominantly led by white populations.

The book is divided in two parts; the first looks into questioning and bringing out the need to redefine craft terms of plot, conflict, vulnerability, character and setting, among others. Salesses highlights that in institutional or workshop spaces, these devices are not recognized as being rooted in the writer's sociocultural context, lived experiences, and realities. For instance, the famous axioms created in workshops of "show don't tell", "kill your darlings", "write what you know" have become universal, and add to further marginalizing the ways in other cultures of storytelling where these may not apply. Salesses reminds us that it's not enough to only push back against the myopia of these axioms, but also to understand the context in which they are rooted; otherwise, "we simply recreate the same exceptions within the same culturally defined argument we were taught to engage in". He draws examples from a broad range of literary work, including One Thousand and One Nights, Curious George, Ursula K. Le Guin's A Wizard of Earthsea, and the Asian American classic No-No Boy by John Okada, alongside dedicated sections highlighting East Asian and Asian American literature, asking readers to reimagine, question, and apply a critical lens on writing as craft.

The second half of the book critically reflects on the traditional workshop models used in American MFA programs. The way in which writing models and workshops operate only too frequently build the idea for minority writers or students of creative writing that their writing only matters if they favour what is striking (about their work, by extension their experiences) to the dominant point of view of their workshops, which, Salesses points out, are white and cisgender. "It is effectively a kind of colonization, to assume that we all write for the same audience or that we should do so if we want our fiction to sell", he says. In this section, Salesses brings depth to his arguments by drawing from his own experiences, and his many years as an Asian-American writer and professor that he relays with quick-wit. The book also speaks for Salesses' expertise as a brilliant instructor, as it is filled with ideas for syllabus design, workshop techniques, and writing exercises.

While the book talks about the ways in which stories are judged or criticised based on cultural biases/expectations of what a "good" story should be, a more nuanced deep-dive into how Western forms of storytelling became dominant and the ways in which other forms of storytelling continue to be marginalised, despite the progress in recognising diverse voices in other spheres, would have been more helpful in identifying where the power manifests and needs to be dismantled.

Whether one is a writer in the middle of navigating the institutions Salesses critically looks at or is an avid reader and lover of the craft, this book has much to offer. It is not simply a reminder that writing is not an artform isolated from the influences of the disparities and inequalities of our daily lives, but it also demystifies the creative writing processes and points to the ways in which gatekeeping continues to occur. As Ursula Le Guin says—storytelling is a tool for knowing who we are and what we want, too. If we never find our experience described in poetry or stories, we assume that our experience is insignificant.

Ishrat Jahan is an early stage researcher who writes in her free time. You can follow her on Twitter @jahan1620.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments