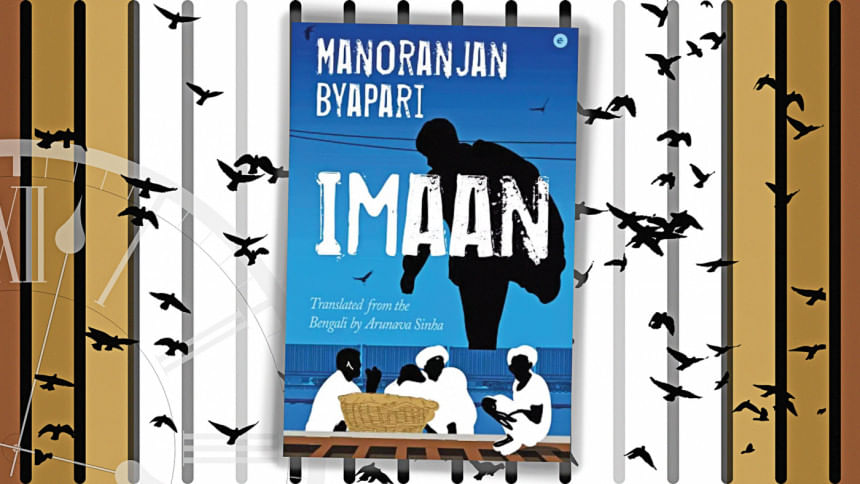

Manoranjan Byapari's 'Imaan': Between the familiar and the alien

Imaan (Eka, 2021), written by Manoranjan Byapari and translated from Bangla by Arunava Sinha, starts on an interesting premise. Imaan Ali, who has spent most of his life in jail and juvenile homes due to no crime of his own, is suddenly released after years of bureaucratic complications and pending paperwork. The novel unfolds through Imaan's perspective on this new world outside the confines of the jail.

This opening scene strikes a chord. Imaan had entered Central Jail as an infant in the arms of his mother, Zahura Bibi, who is charged with the murder of her husband and dies when Imaan is six years old. Jail and juvenile homes are all he has seen till now. A man in his early 20s, with no real knowledge or experience of how the real world works, is now at a loss with the newly found freedom that he had so desperately wanted all his life. He finds a place to stay at Jadavpur Railway Station and a job as a ragpicker at the advice of a consummate pickpocket.

This life of hardship and uncertainty makes him want to go back to prison again. All one needs to do is get in trouble. But for Imaan, who finds himself unable to commit crimes due to his eponymous morality, it was seemingly easier to get out than it is to get back in.

Through Imaan's interactions with the world outside of the central jail in Kolkata, we meet rickshaw pullers, street hawkers, and tea-stall owners, who belong mostly to the lowest strata of the society and come from highly marginalised caste and economic backgrounds. Byapari's social commentary on these characters' lives paints an accurate picture of the reality lived by the ostracised. He portrays the vulgar disparities faced by them in society, along with the more personal human emotions of love, attraction and jealousy, reminding the reader of the writing of Manik Bandopadhyay.

The characters in this novel, however, have very little development. It seems that they are involved only in so far as their descriptions, not to contribute to the story or to the development of other characters. It is Arunava Sinha's effortless translation that makes it an easy and smooth read.

What the text excels at is empowering its women characters. They have diverse stories to tell, but their experiences of belonging to a marginalised community are connected by the ever-penetrating male gaze. Yet all of them reclaim their lives as their own. They are, in every way, their own bosses, living lives in their own conditions and claiming the rights to their bodies and sexuality, owning their polyamory with pride. Take Kamini, for example: a woman who adopts polyamory when her first husband brings another wife for himself. "If you can have this life, so can I," is how she starts before building for herself a life that relies on no one. Such honest and closer to life portrayal of a woman's strength is quite rare.

My expectations of seeing the world through Imaan's eyes, and getting into his psyche, however, remained unfulfilled. The story never quite reaches a climax and keeps the reader wanting for more. One wants to see the other characters through Imaan's eyes with all his bewilderment, rather than the narrator's, to get to know and understand him more. One wants to see Imaan rise to the occasion. But his experiences don't contribute to his growth and do not let him take agency of his own life and its decisions. Till the very end, he remains the same naive and bewildered boy who comes out of jail with no experience of the outside world. Imaan is, eventually, a novel that fails to sustain the intrigue of its premise, but it is also an excellent example of class and social commentary in its rawest form.

Nahaly Nafisa Khan is a sub editor at the Metro desk, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments