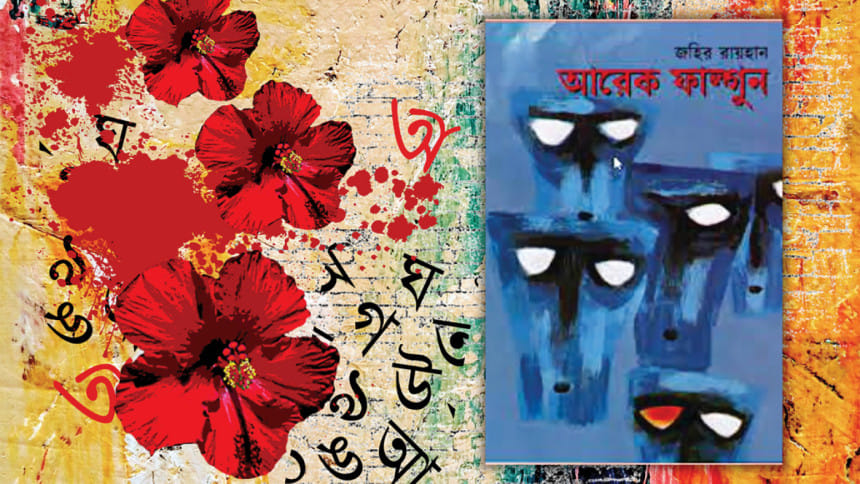

The book that rebelled: Arek Falgun by Zahir Raihan

When we talk about a book involving war or revolution, we expect unity to be the first motive that draws us in. Set in 1955, the story of Arek Falgun by Zahir Raihan revolves around a group of student protestors gathered barefoot in front of the Shahid Minar. The duration in which the novel is set is short in that it follows a duration of only three days and two nights. Raihan displays metaphorical nuances of camaraderie between the student protestors – all of whom come together to make a statement. This is also demonstrated in the naming of the book because after all, spring brings hope, of something new and better.

In the novel, one of the most significant themes is the student's demand and rejection of any kind of law enforcement in their beloved Dhaka University. In any case, why should they allow weapons to enter their fortitude of progress and education where they are taught knowledge is power, and the only weapon is their pen?

The book is not only ardent in its refusal of authority but also speaks of detaching oneself from aspects of one's life that add meaning in the pursuit of revolution. Munim, one of the main characters in the novel, is seen to be rejecting his love for Dolly in a struggle against power.

Additionally, Zahir Raihan's depiction of women involves portraying them with courage. The women in Arek Falgun, a book written in 1969, have basic autonomy as they are the ones who choose their partners, contribute proactively to conversations, and participate in the movement on their own volition. He also sparks conversation of motherhood through Asad, one of the protestors. According to Asad, had he not been an orphan, then it would hurt his mother to see him walk the path of rebellion.

In Arek Falgun, while Kiyo Khan plays the significant role of an antagonist, it's the self-proclaimed artist Bazle Karim who rejects the student movement and his peers' attempt at civil obedience. In contrast to Bazle, Zahir Raihan also gifts us Kobi Rasul, a poet and one of the pioneers of the student movement in 1952 in the book. Despite losing friends, and being enraged and hurt, he strives for freedom to speak in his mother tongue. Perhaps a cry for one's mother tongue is not cumulative of merely preservation but also of the ability to speak freely as one wills, which is an emancipatory act in and of itself.

In fact, it is Kobi Rasul, who said in Bangla in response to a police officer's aggravation on not having enough room for all the detained student protestors at the end of the book – the lines which have immortalised Zahir Raihan's Arek Falgun: "Ashche Falgun, Amra Kintu Digun Hobo" (We will be doubled by next spring.)

By chanting slogans as powerful as "Barkat er Khun Bhulbona", by hailing black flags and adorning black badges, and not backing down on being hit with brutality, the students resisted and honoured the lives of their peers they lost years ago. Such has always been the case of revolution because to commemorate is to not only grief but also to love and rebel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments