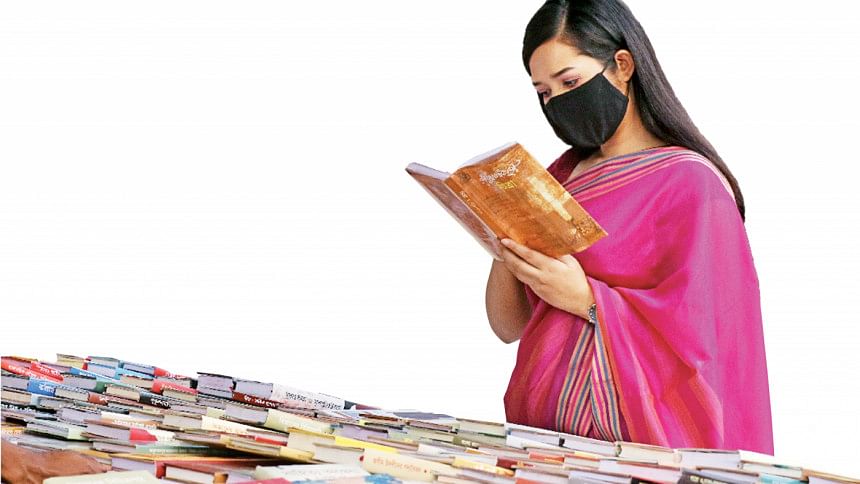

Boi Mela begins. Are publishers prepared?

The Amar Ekushey Boi Mela of 2022 has begun again after much apprehension, delays, and uncertainties. We are once again faced with questions about how we want to see the Ekushey Boi Mela performing this year, particularly since the fair was a disaster for most publishers in 2021.

First, the government authorities are always behind in planning and leave things for the last minute to reach concrete decisions, and often, these decisions don't take into consideration pragmatic solutions that are sustainable and maintainable in the long term. The pandemic and the uncertainties associated with it have definitely contributed adversely in this tendency of waiting for the last minute to decide on the course of action for any public gathering. However, for a book fair that involves heavy investments, both from the state and private entrepreneurs, it is not well understood why a planning framework cannot be developed ahead of time, so that all stakeholders can formulate their game plan accordingly. It is only fair to everyone involved that they know what to expect—whether there will be a fair or not; if yes, then in what modality.

From the beginning of the pandemic, we knew that there will be a "new normal" which will inevitably be hybrid in nature. However, we paid no heed to this obvious possibility, and made no effort in engaging into a sustainable and forward-looking plan that will not only apply for the pandemic period, but will also be relevant for a post-pandemic "new normal" phase.

Many discussions, consultations, and proposals took place in the direction of the new modality of the book fair last year, taking into consideration the business interest of the publishing sector, safety precautions for people attending the fair, and also the newly developed online-purchase behaviour of buyers. None were executed, however, and we ended up being subject to an ill-planned fair, part of which was further affected by another lock-down towards the middle of March 2021. The publishing industry was held hostage to poor and reactive planning on the part of the implementation institution (Bangla Academy), and an ill-informed and short-sighted advocacy from the publishers' associations.

We could have used this year as an opportunity to prepare with a more equipped arrangement for a post-pandemic period; but Bangla Academy and the publishers' associations made little effort in truly utilising our talents and expertise that were fully capable of delivering such a plan. We expect more decisive leadership from Bangla Academy as an autonomous body. Their inability to formulate a pragmatic plan for the book fair independently, based on the health ministry's directives, have affected the most important book event in the year, and in all likelihood, the outcome will be less than expected this year as well.

In an interview earlier in the year, I was asked why publishers in our country are claiming that they have incurred "huge losses" whereas some surveys show that people read more during the pandemic. Global data also shows that the publishing industry has not suffered the pandemic nearly to the extent that was initially feared. According to the World Economic Forum, book sales have gone up in the UK and US markets, and appreciation for print books have revived.

My response (based on instinct in the absence of hard and reliable data) is four-pronged: (a) this sector in Bangladesh is plagued with unplanned and reactive initiatives rather than long-term, informed market analysis and sustainable solutions for players of all sizes and nature; (b) the distribution and production eco-system we require for a functioning publishing sector, with robust backward and forward integration, is largely absent in our country; (c) our production costs are unnecessarily high (we bear the burden of an insane amount of tax imposed on paper), therefore making our product uncompetitive in the regional market; (d) we have been extremely tardy in jumping on the online sales and eBook bandwagon.

These have been age-old problems of the sector, but they have come back to bite us harder when times are bad. A handful of private enterprises who were prepared with their platforms and ammunition, namely Rokomari.com, Baatighar, Prothoma, predictively fared well through online sales.

Why have we not made any active effort in reducing the cost of production or focused on a functional distribution network in Bangladesh? Again, my short answer would be that most publishers who provide leadership in the sector don't care much about the actual readers in the country. Their priorities are catering to various projects, government purchases, and to non-authors who are prepared to finance their book production. These are unavoidable realities in a market where true commitment to developing and promoting readership is largely absent, and the knowledge ecosystem hardly supports the survival of a true publisher.

The pandemic gave us a much-needed push to move to the next level of publishing and for connecting with a changing world that we were choosing to ignore. How smartly we respond to this push will determine our sustenance and relevance as an industry.

Mahrukh Mohiuddin is Managing Director, University Press Limited (UPL).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments