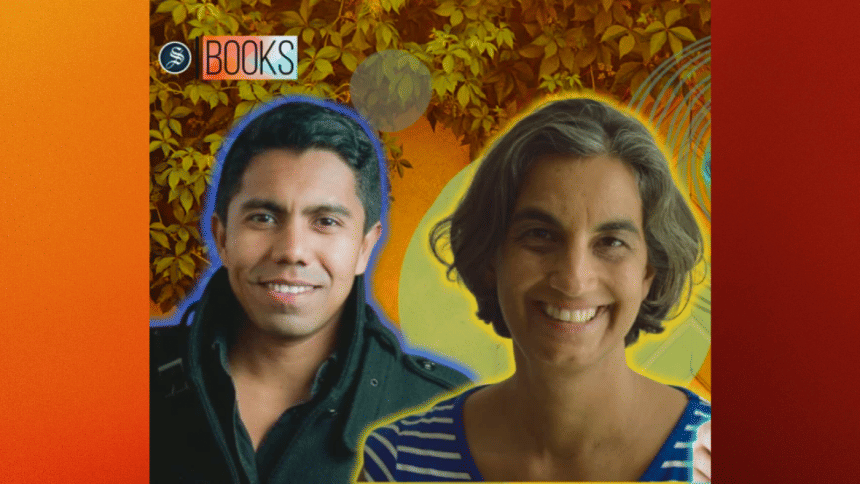

In conversation with Anjali Singh and Arif Anwar

Recently Daily Star Books and Star Literature sat down to have a conversation with Anjali Singh about her experience as a literary agent and her time at the Hermitage Residency. Arif Anwar, the curator of the residency also took part in the conversation moderated by Nazia Manzoor, editor of DS Books and Literature.

Singh had started her career in publishing in 1996 as a literary scout. She was formerly Editorial Director at Other Press and had also worked as an editor at Simon & Schuster, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, and Vintage Books. She is best known for having championed Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis (2004). Arif Anwar is the author of the novel The Storm (2018).

Let's begin with your experience at the residency. Now that it's done, what was significant about it? What stood out to you?

Anjali: I don't know if Arif consciously modelled the residency in this way, but we in the US have quite a number of literary spaces that are deliberately in place to help young writers improve, and also build community. As someone who doesn't teach writing but talks to emerging writers about how to get published and what that journey looks like, the starting point really always is building literary community.

This includes finding early on in your writing career people who are like minded in that they care about writing and also can be your readers. As long as you're learning, you need a critical reader whom you can trust. And it can't be your mother. It has to be someone who is a peer, who's also struggling, and trying to do what you're trying to do. Thus, part of the purpose of MFA programs in the US, and these residencies, besides finding their mentors, is to bring young writers into a community. And I think those two things are so important. Something that we in the US like to pretend that everyone does everything by themselves, it's all individuals and bootstraps, when actually, everything in life is community.

It's about who's there, who has your back, who believes in you and helps you believe in yourself and who helps lift you up, right? Who gives you the information you need at a critical time that helps you unlock certain doors?

For me, it felt like this was the purpose of this residency and really what it is achieving. This was the second cohort. I wasn't there for the first one, but what's true for both cohorts is concrete writing instruction from Arif Anwar and Julia Philips.

I think of myself as someone who just really enjoys people, bringing people out, and hearing about what they're working on. I think helping to create a sense of community and fellowship throws away a lot of the hierarchy, which I also think is embedded into South Asian culture as much as it is embedded in other places, right?

The cohort was diverse—we had writers who are still in college and someone who graduated from Harvard in 1970. I think that's a beautiful thing too, to bring people together cross generationally. It feels like a very important part of my mission, being someone who's been in the publishing industry for 27 years in the US, and one of very few people of colour. I saw how it works, what a club it is, who it keeps out, how racist it is, right? So, wanting to truly feel like a changemaker, having been through what I've been through but also having all the contacts and information and relationships that I have and using that position, my positionality and privilege that I have to bring more people, more writers from the Global South, whatever I can do into the market. And we'll just help them be writers. I don't think they have to be published in the US, I don't think that has to be the be all and end all for anyone. But I do think it's helpful to reframe why that is the goalpost and why it's important to also think about your own market, think about your own literary traditions.

One thing we appreciate about what you're saying is how representation is something we need to talk more seriously about. As we know, we are underrepresented even within the South Asian canon so in that sense, it's really important for us to try to break into the space that if not restricts our entry but certainly makes our entry a little difficult.

Anjali: I agree. I want to see more stories from Bangladesh out there in the world.

I would like to talk a bit about the writing workshop part of the residency. What were the conversations and discussions like? Did you have a specific approach or vision behind how the classes and workshops were designed?

Anjali: This is a very good question, and I don't know how directly I'm going to be able to answer that. As someone who pulls people in from the margins and the outside, I'm actually not that intimately involved with MFA programs in the US. I do meet with students sometimes but so many people feel like they need an MFA to break into publishing but I'm the opposite. I think if you have an MFA from Iowa, 12 other agents are going to jump on you, and I don't need to be that person. I'm the person who's really coming without a way in. That's one thing. The second thing is, at this residency we weren't reading each other's work. We did open mics which was really the only time we got to hear each other's work. We weren't distributing stories. Everyone was in such different places. Some people came really with just "I have an idea about a book I want to write but I have a day job". Other people came as poets, so we weren't there to read each other's work critically. We were there to build community, be resources for each other. I was definitely there to answer questions about anything—my career in publishing. Because I think it is a big deal like you said to be sitting in Bangladesh to have access to an agent who knows a lot about how to get published, how that world works. We also had Nadeem Zaman (author of In the Time of the Others, Picador 2018) come in and talk about his experience of finding an agent and publishing, which was relatively hard for him.

What was the publishing experience like for you?

Arif: I think I got lucky—I had a good book and so did Nadeem but beyond the instinctive resistance the industry has against non-white, non-American writers, sometimes you get lucky, sometimes you don't. And Nadeem had some things work against him, like Anjali said, being in academia and coming from outside the fiction writer community, so it was bad luck and historical obstacles that are in the industry against people like us.

Anjali: I haven't read Nadeem's book but it's about the war, right? I feel subject matter wise it was also a little harder of an entry point than The Storm was. Because one of the things I loved about The Storm from when I first opened it was that so much of South Asian literature is about a particular class. And it doesn't even question it. And here Arif was putting us in this world of fishermen and fishermen's wives. So at this residency we talked about Arif's journey, finding an agent, the editorial process we went through together—I feel like all of that is storytelling, but it's also demystifying a process. Where else would you have access to such stories? We need these origin stories. And Arif talked a lot about the research that he did. Yes, he was an outsider, but you brought all your research skills to the table like I'm going to crack the code, I'm going to figure out how to write the perfect forwarding letter.

...probably the keyword here then is demystifying the process because it is such a mystery to us. There's great writing being done but there's a lot of mystery surrounding the process of publishing itself. I guess that's the strength of the residency to bring that insight, to bring that knowledge to a group of people who are curious, who have the potential and who can potentially make change happen in this field for us.

Anjali: And who without this may not ever find the resources or self-belief. Because a lot of it is having faith, knowing that you're going to keep doing this and having an understanding that this is a long, long road. I don't know enough about how publishing works there and if I'm lucky enough to come back I would want to spend more time talking to publishers, getting a little bit of a sense of the life on the ground.

You have an illustrious career—I am fascinated by you being the first champion of Persepolis. What draws you to a book? What stories do you want to see make it big?

Anjali: Persepolis is 20 years ago. I was a brand new editor and I hadn't published anything before I found that book but I think the timing was very important. It was February 2002 and 9/11 had just happened. I did understand the rhetoric—my dad is Punjabi Sikh and my mom is white American—because I have my father's perspective which was always critical of America and American exceptionalism and I grew up a brown person in a very racialised country. When I opened the book you could tell on the very first page that she has a sense of humour. So the way you related to her story was so immediate. And one of the reasons it has worked so well is she did deliberately write that book for a Western audience. I like books that are political. I love to look at "the political" through a very personal lens.

Where I was going with this is to draw attention to culture. Part of my mission is to deconstruct publishing as a monolith. It is made up of many different cultures and part of your journey as a writer is to figure out who you are in conversation with, who you are trying to reach, whose books you are sitting on the bookshelf with and what particular culture within publishing might actually be the right fit for you. So often in this industry, subjective decisions are passed off as objective. Who is the audience, who do we think the audience would be and how much who I am in this world determined who I knew and thought the audience would be. This is what guides me: my conviction that the books that I see value will have an audience.

Let's talk about some of these technicalities of having access to books in this country. If you are a Bangladeshi writer writing in English and you are publishing from the United States or Canada or anywhere else, how do we get access to those books?

Anjali: So this process is very colonial. The US and the UK duke out who gets to distribute their book in South Asia if we don't find a South Asian publishing partner. But the UK really doesn't like splitting those rights out because they like making money selling their editions in South Asia. So even within this continent, if India controls the publishing industry, they will have the rights and they will distribute in Bangladesh and Pakistan.

Arif: Interestingly, this has been a proud tradition in Bangladesh. The whole model of the publisher paying to publish someone's book or paying an advance is just not a culture that exists. And with the exception of the 1% of writers, you know, someone at the Humayun Ahmed level, most writers pay out of pocket to publish their books and recoup that money by selling the book themselves. Maybe it's changing slowly now but it's a cultural thing. The expectation is that self-publishing is the norm for most writers starting out and that's an impediment if you want to order a thousand copies it's going to cost a minimum of one lakh taka or a thousand dollars. Which may not be a lot for US money but a lot for someone in Bangladesh.

This might be a tired question but where do you think we stand on Bangladeshi writers writing in English?

Arif: It's sort of a marathon. India and Pakistan and even Afghanistan to an extent are sort of ahead of us. Because we are a younger country, the '71 war of independence casts a big shadow on our literature the same way WWII casts a shadow on western literature. Which is understandable. It's a recent traumatic event. But I do think we have a variety of very compelling stories that we can write. We are getting there slowly but surely. There's a new wave of writers out there and the Hermitage Residency is a way of creating that community in the country and towards normalising the idea of writing in English. I just see writing in English as a tool. English is a tool. If I were to sound very revolutionary, I would say I am picking up the tool of my oppressor. Every time we use English, we use the master's tool. It's a flexible language and the intent is to use the medium that will help you reach the widest possible audience and that's why I write in English. Those are just some of my scattered thoughts. And a concerted effort to write in English started only around 20 years ago.

Anjali: I'm also going to be cynical and say Afghanistan got a lot of attention because Americans pay attention to it since we fought a war there. I come from a pretty cynical place after being in this industry for so long. In the children's book world for instance, there is a robust conversation about representation. They publish in a more mission driven way, are in conversation with librarians and teachers and there is just more space. The adult publishing world tends to think much more short term. I feel like India had its moment, but Bangladesh never did. Nigeria had its moment. Right now, anything South Asian feels like a hard sell. In 2020, the conversations around representation meant we have a lot of black editors which is a wonderful and necessary corrective. But Asian Americans are not part of real conversations around representation. Publishers don't see our value and I feel like who the gatekeepers are really does have a huge difference. You just have to live with a lot of rejection and realisation that this industry doesn't value what I value. But then again, we had Persepolis and that changed a lot of perceptions. I feel like we haven't had that for Bangladesh. But there's always space for really good books to break through.

Arif: It's important also to not restrict ourselves to only certain types of stories—generally the south Asian writers consciously or unconsciously tend to fall back on the trauma narratives. On the back cover of the book you will read the words "shattering" or "war torn", "shadow of war", some sort of struggle. We have joyous stories, we have funny stories, we have scary stories that don't always necessarily have to be oriented around war or trauma or immigrant experience. So for our writers to really find a story in which they have conviction and to not write with an eye towards this audience and that audience and acceptance in this market or that market—that's going to be a very freeing thing. That's going to help them write an awesome story. As I'm seeing more and more people of colour in the publishing industry there is an increasing appetite towards stories that aren't simply the dreary, literary, bleak stories about war and loss and death. So, have a good story that you believe in and you love, and write it with all your heart and success will come, I think.

Anjali: I think the literary canon has made more space for edgy stories. Stories that are told in unconventional ways. And I think that's a positive change in the US. On the one hand a lot of books that have worked in the US are written towards a white audience. That's actually the thing everyone has to work against and fight against. The work that will stand the test of time are not written that way and because they are not written that way, they will travel.

Arif: We heard a lot of great stories during the residency.

Anjali: I remember one that was a beautiful funny story about adolescence. It was about being a girl and exploring her sexuality in the very provincial world she's in and I could see a whole novel there.

Arif: None of the kids this time were from super privileged backgrounds. Their critique, their analysis, their reading list—all of that was top notch. I was really impressed with the batch that was there.

Anjali: I didn't come in with any expectations. But I just had the most wonderful time. It is a beautiful thing you've created, Arif.

...and not having the financial burden to pay for the residency was also beneficial.

Arif: Anjali gave me the idea, we can perhaps do a tiered thing next time with a free tier for those that need it. I don't want financial need to ever be a barrier for someone attending.

Anjali: It was more special than I could have imagined. My dad was a photojournalist during the war and he was here in November 1971. So I have always had a connection to Bangladesh but to be here for a reason and purpose and to be helpful was so inspiring.

Arif: We're going to have you back.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments