An exploration of the history and panoply of Indian Subcontinental cuisine

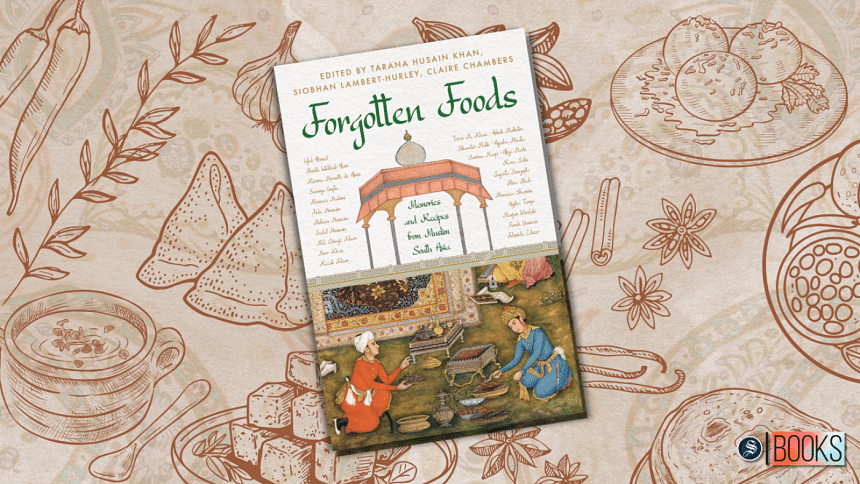

In my quest to devour "concealed" history, I chanced upon Forgotten Foods: Memories and Recipes from Muslim South Asia, edited by Siobhan Lambert-Hurley, Tarana Husain Khan, and Claire Chambers. I thought it would relieve me from all the stress of scrolling uncontrollably through snippets of history buried under dubious layers spanning 53 years and the daily updates of the countrywide chaos. I was right—Forgotten Foods whisked me away to a different world. This collection of family recipes, anecdotes, and essays is not to be taken lightly for those who eat to live. It's chock-full of culinary history shaped and mutated by classism, ageism, colonialism, identity markers, migration, and other factors. And, for those who live to eat, Forgotten Foods is a repository of recipes from the simple saag (leafy greens) to the more nuanced Calcutta Mutton Biryani, a must-have for professionals and home cooks.

As diverse as the Indian subcontinental cuisine is, the book, however, has a higher purpose. This collection focuses on Muslim South Asian cuisines since the Hindu way of consuming food has been labelled as "Indian" throughout the 20th century, thus diminishing the contribution of Muslims since the 7th century to our regional gastronomy. With rich contributions from storytellers in India and Pakistan and a heavy focus on those Indian cities with a distinct Muslim heritage, Forgotten Foods is a labour of love that puts the spotlight on the Muslim minority in India and paints their culinary contribution with a positive hue.

Moreover, it is one of the spin-offs from a larger project called "Forgotten Food: Culinary Memories, Local Heritage and Lost Agricultural Varieties in India." This project aims to fulfil some of the UN's sustainable development goals by improving the lives and opportunities of the people in the region. The three editors of Forgotten Foods have been directly involved in this project, which used the combined efforts of academicians, food historians, plant scientists, farmers, chefs, filmmakers, and other professionals to set off several projects like food festivals, regular columns, the revival of lost rice varieties, a cookbook based on 19th century Urdu and Persian manuscripts, a collection of essays, and so on. These assignments help us understand how food is more than just a way to quell hunger and nourish our bodies; it also defines the culture, history, and identities of people.

Through Forgotten Foods, we get deeply-etched glimpses into the lives of Muslim communities from all strata of society. The first chapter by Muneeza Shamsie is an account of her father's penchant for cooking, her British boarding school education, elaborate parties held at her Karachi home for British guests where European or English dishes were served, the finest china and tableware, liveried servers, traditional Eid fare, coffee mornings, and milads. She pays homage to their home cooks for their outstanding culinary skills. What stands out is how the family's culinary roots in Lucknow and Rampur and later, their food experiences in London, never clash but take their own place as per the occasion. A Christmas cake for Christmas and seviyan and halwa for Eid. Another point that strikes me is how the usual gender roles are reversed in their home. While her mother was mostly into baking, her father cooked more elaborate dishes like nihari, paya, and even Continental dishes, despite having a regular job at Pakistan Tobacco Company.

In sharp contrast, the second chapter by Moneeza Hashmie, daughter of the famed poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz, is a short account of her parents, their no-frills lifestyle, and simple food habits. While Shamsie's account of elaborate meals where the whole family dined together evokes a sense of luxury and impeccable table manners, Hashmie tells us how her father was hardly present at meal times and how her tiffin in winter consisted of a roti and a curry or daal. Shamsie's story spans 29 pages, whereas Hashmie is done with her sparse story covering little more than five pages, including her family recipe. The recipes are also a striking contrast to each other—a luxurious Qiwami Seviyan by Shamsie has a tall ask of ingredients like saffron, cream, butter, pistachios, and other ingredients, whereas the humble Sarson ka Saag and Spinach offered by Hashmie is a basic vegetarian recipe, though it does require a knob of butter.

In between these widely contrasting family accounts and recipes, Forgotten Foods offers a vast repertoire of anecdotes, historical origins of foods, and explanations of culinary terms. Filled with nostalgia and flavoured with tasty recipes, the book is a rich, olfactory experience that shares stories where borchis and khansamas (the difference is also explained in the book) connected generations of families through gastronomy. It entertains us with stories on how Taran Khan's Nanna's hamper of prepared food for travellers passing through her home in Aligarh represented unadulterated food, family bonding, and family honour. Or, how Claire Chambers' taste buds changed forever after her sojourn in Peshawar and Hyderabad (Indian side). A fascinating four variations of adrak halwa (ginger halwa) by Tarana Husain Khan is a light and fun read, while Farah Yameen's story is a sarcastic jab at how food can be a class divider. Rizvina de Alwis offers a unique glimpse into the cultural and culinary history of Malays in Sri Lanka (a minority within the Muslim minorities), the festivals that brought neighbours from all religious backgrounds together, and how Wahhabism is causing the Malays to lose their identity. Aliya Nazki's short but powerful discussion on why Kashmiris take it as a personal affront when original Kashmiri recipes are mutated helps us make better sense of those who have been suppressed for years. Sheikh Intekhab Alam shares how, in Odia Muslim culture, young children are given the heavy responsibility of mending relations with families. This is done during Eid by offering a large tiffin called the bakhra.

Forgotten Foods depicts culinary delights in its various roles—as a divider, leveller, Hambastagi among refugees and the diaspora, connection to the past, and a celebration of life. The stories from Rampur, Lucknow, Allahabad, Bhopal, Manipur, Delhi, Ladakh, the Malabar coast, Karachi, Kashmir, Bihar, and other places in the Indian subcontinental region provide a deep look into our shared history and culture generously peppered by culinary differences that make us unique.

Zertab Quaderi is an SEO English content writer and social media marketing consultant by day and a reader of fiction and nonfiction books by night. In between, she travels and dabbles in watercolour painting.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments