Falling through the cracks of the ‘normal’

There is something to be said about the innate process of otherising a person with disability, and pushing them out of the group of the 'norm' and into the group of the 'exception'. That a body can be politicised in such a manner that anything considered 'less than' or 'different from' the ideal body can be labelled as an outcast is a cultural and political practice we see everyday. Often, the disabled body is treated as an entity that is less than human, and literary portrayals of those marginalised and socially ostracised beings can sometimes attest to such social and cultural norms.

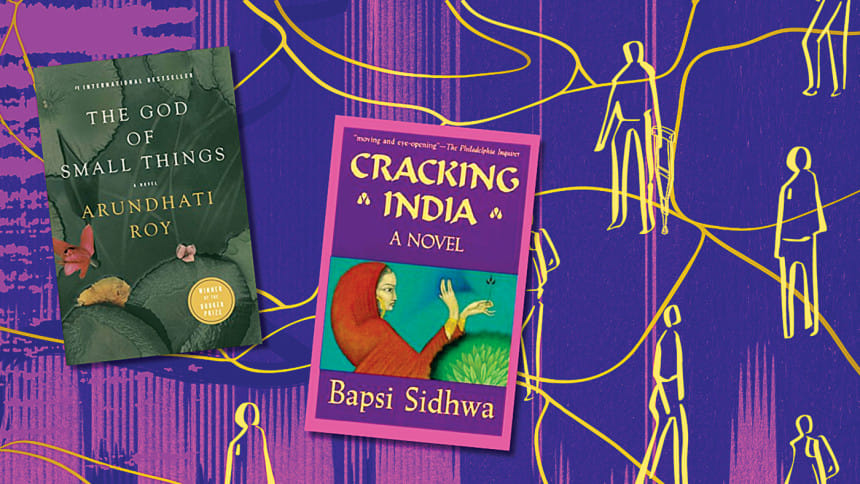

In Bapsi Sidhwa's Cracking India (originally published as Ice-Candy Man, 1988)—set during the tumultuous days of 1947 Partition—the main character, Lenny, is a Parsee child who suffered from polio as an infant, and was left with certain disabilities as a result. Towards the beginning of the novel, Lenny's disability is at the forefront of the story. After a series of treatments that failed to give Lenny the degree of mobility her parents had hoped for, her doctor Colonel Bharucha suggests Lenny live a "happy, carefree life".

The idea that her aspirations, motivations and goals should be connected to, and weighed down by her physical disability portrays the ableist nature of the perception of disability, and thus, that the able body is superior to the disabled— giving Bharucha the power over Lenny to make important life decisions for her.

Colonel Bharucha's immediate reassurance that she would be "quite normal" establishes and introduces us to the phenomenon of considering a person with disability to be not normal. Thus, a person with a body that is in any way different from what is considered "whole" and "ideal", is abnormal and is in the need to be "fixed". Moreover, Colonel Bharucha decides to restrict Lenny to a "strain-free" life. While consoling her parents regarding the permanence of her condition, he says she would not need to be educated, and could always get married and lead a happy life. In all of this, her disability is made to be the cause for which Lenny needs to settle, insinuating that a life with disability must be reduced to mediocrity, without the need for better things, or higher achievements.

While a happy conjugal life without an education or a career may be a perfectly fulfilling life for some, it must be taken into consideration that Lenny had little to no agency in deciding the course of her life, and that the ones making the decision for her were neither conditioned to disability themselves, nor did they think that getting married and not receiving an education was the best course for a fulfilling life. Of course, Lenny's polio does not prevent her from receiving an education. Rather, it is the assumption that an education, or striving for more, would "strain her nerves", and so she should just aspire to marriage and children and be happy with that.

The idea that her aspirations, motivations, and goals should be connected to and weighed down by her physical disability portrays the ableist nature of the perception of disability, and thus, that the able body is superior to the disabled—giving Bharucha the power over Lenny to make important life decisions for her.

In between two of Lenny's appointments with Bharucha in the novel, Sidhwa mentions 'a happy interlude'. Here, a four year old Lenny still goes to school with her cousin, and tricks the teacher into believing it is the cousin who is with disability, thus letting Lenny play with the other children. As Lenny shouts, plays, laughs, and runs on the tips of her toes, it can be seen that she has not lost as much mobility and function as is assumed about her. Lenny is happy when she can shrug off the lopsided weight of her disability, and more precisely the weight of the fear of her disability pushed onto her by her parents.

Furthermore, when the teacher asks the children which of them were 'sick', she is most likely throwing the word around mindlessly, as do so many other people, usually without disability. Lenny is not sick, she is not suffering from an illness that causes symptoms or needs immediate care or medical attention.

However brief, the use of this word "sick" not only portrays society's likeness and willingness to bunch together people conditioned with different ailments or illnesses and people with disability under the same umbrella, but also tends to legitimise the hierarchical dichotomies (able-bodied/disabled body) of the political body, and the resulting hegemonic power of the norm over the exception, or the ideal over the less-than-ideal.

It is these biases, and the ingrained sense of superiority that comes with these social constructs, that allow for an imbalance of power. After all, given the legacy of colonialism and the colonial contact, there is always an eagerness for power imbalances to form, in any group. One would always like to convert their privilege into a source of power over those that lack said privilege.

Take the character of Velutha from Arundhati Roy's The God of Small Things (1997), for example, who is a communist and an "untouchable" (from a caste lower than the protagonist Ammu and her family). A carpenter hired to work in the family's factory, Velutha's life is entangled completely in his socio-political standings and is ultimately upended by his relationship with the upper caste Ammu. Even Rahel, one of Ammu's twins who loved Velutha during Sophie Mol's funeral, imagines someone painting the high domes of the church, and thinks to herself, "someone like Velutha" must have done it, grouping him with those of lower caste in society.

In Ammu's dream in Chapter 11 of the book, Velutha is seen to only have one arm. It is also portrayed that within Ammu's dreams, his actions were restricted by his 'disability' and the consequence is described as having no impact; "He left no footprints in sand, no ripples in water, no image in mirrors." The choice to portray Velutha, a clearly marginalised character with a disability within his lover's dreams holds significance.

The most literal way to interpret his dream-disability would be the disability as an allusion to having no agency, no instrument to carry out his wishes and will. That the absence of one hand shows that he is always subjected to a choice. He cannot have it all, even as he should be able to. It shows the nature of the choice he is subjected to as well, that he has little to no bargaining power, and it is out of his reach to rectify the situation.

His dream-disability also brings into comparison the post-colonial condition of racial and ethnic discrimination and the impossible odds stacked against the disabled body. Through the dream, we can interpret the idea of him being scrutinised at all times, the scene reminiscent of a panopticon.

It should also be noted that the disability is only manifested for Velutha, and not Ammu. A direct and deliberate reference to the conditions they are subjected to, portraying the clear contrast. While they are both subjected to scrutiny, because of Velutha's caste and political ideologies, he is the one at a greater disadvantage, with greater limits to his agency.

Lastly, Ammu mentions the lack of footprint and ripples on Velutha's part, and on that note, I would like to argue that for Velutha, and his disabled self in the dream, it portrays the absence of a mark left behind for him. His existence in society and in Ayemenem as an untouchable leaves little to no mark in its threads, and in the greater fabric of India, in reference to his communist protests and later, his death.

Thus, through the works of Roy and Sidhwa, my argument stands—the portrayal of disability is more than what is written, and is an effective tool that allows for the reflection of the lives of those cut off and pushed away from society based on their choices and identity.

In the past couple of months, Bangladesh has seen a fair share of chaos stirred within what was initially a fight for freedom, and what later turned to a desperate call for reform. With what has happened especially in the past few days with all the reports of lynching, mob justice, and communal violence, I wonder if we will ever collectively stop trying to settle scores in the name of justice, and stop creating more divide in our inherent need to gain control and power over those our society has deemed unworthy or 'less than'.

Syeda Afrin Tarannum is a sub editor at Campus, Rising Stars, and Star Youth.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments