Finding myself in Orhan Pamuk books

Through books, while we read the stories of other people, we are often just looking for ourselves. At least, that's what I was doing, quite literally, when I thumbed through one Pamuk book after another.

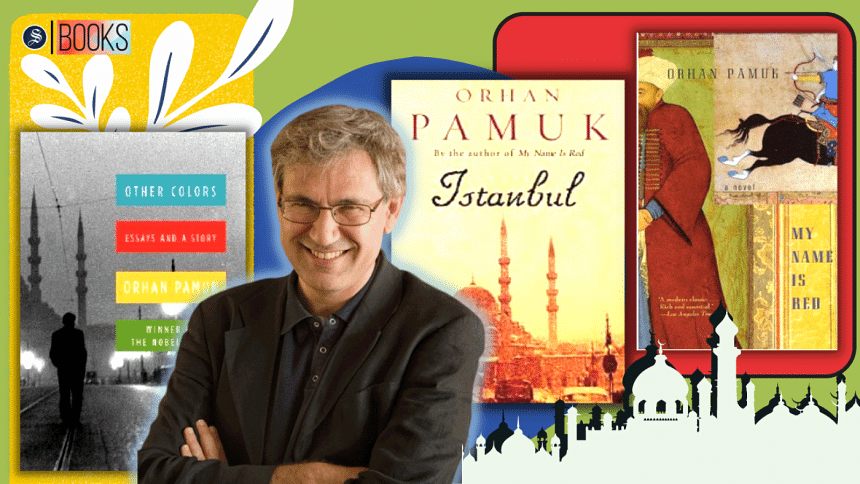

I was stuck on a particular word on page 305 of Istanbul (Faber and Faber, 2006), a memoir by the Nobel prize winning author. It was a four-letter word. It is most likely one of the first two words I learnt to write. I had written it in my school diary. It is also etched in the corners of multiple pages of the notebook I am writing this draft in. It is on my passport, also on my pajamas. It is the word the world knows me by—my name. Specifically, my last name, Nuri.

That's how I found myself in Pamuk's writing: through my name. But instead of the young lady that I am, the Nuri in Pamuk's memoir was a man. A man being chased by the police. He was Pamuk's publisher friend to whom he would be sending a translation of a Graham Greene novel to earn some quick money and pay the rent of the apartment in which Pamuk had been secretly meeting and painting his first love.

My last name, Nuri, is derived from the word 'Nur,' which means light. Certainly a desirable attribute to have, and this perhaps explains away its popularity in Muslim names. Hence, the chance of spotting Nuri in a Turkish author's book is not as low as that of spotting a blue moon. Yet I leaped for joy.

To add to my delight, I showed up once again. Nuri was in My Name is Red (Vintage, 2002), the book Pamuk won the Nobel prize for. I was relieved to know that this time, I was at least not being chased by the police. In fact, I was being addressed as Nuri Effendi. Only in Pamuk's historical fiction set in ancient Istanbul could I be a miniaturist! But even now I don't have the good fortune of being an accomplished one. This is how I had been described:

"As happened to many miniaturists, Nuri Effendi had grown old in vain, without having fully experienced life or become a master of his art."

While I was suffering the pangs of mediocrity, in the following pages, Pamuk's character, Black, as if to console me, said,

"... Nuri the miniaturist, much subtler in thought than I had assumed…"

Satisfied at my subtlety of thought being recognised, I stumbled upon another feat of admiration for Nuri Effendi. On his work table lay a royal insignia which he had gilded in gold for the Sultan himself! It's not everyday that we are bestowed with the window of time and imagination to assume the role of an ancient miniaturist in Istanbul. Though totally unaware, Pamuk dropped this little opportunity for me through his book.

My third encounter with myself happened in Other Colours (Faber and Faber, 2002), a collection of essays by Orhan Pamuk. This time, I finally saw myself in a craft I sometimes dream of being involved in. I was the novelist Resat Nuri Guntekin who drew the provincial pictures of Turkey through his written words. When Pamuk commented that his novels couldn't entirely capture the essence of Anatolia, my heart sank a little. But why I was so invested in the success or failure of this novelist with whom I share nothing but a nominal attribute, I couldn't tell.

I am connected through name with many other people too. In fact, in my class, I share my first name with two other people and my last name with one. I can't say with conviction that I ever felt as excited to encounter real namesakes as I did when I stumbled upon the Nuris in Pamuk's books. Our similarities are only in the name—yet this joy and emotional investment in how they turn out to be! Looking for myself in Pamuk books made me experience this simple and naive version of self-discovery, if we can call it self-discovery at all.

Noushin Nuri is studying business in school and literature at home. Reach her at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments