How I found my voice as a debut author

Ahmed Sofa's famous 'chanachur' metaphor frequently comes up in discussions on literature, namely 'healthy literature'. When Humayun Ahmed reigned as the top writer of Bangladesh, Sofa unapologetically referred to his one-time protegé's later works as a lucrative snack—pleasurable to consume, but ultimately lacking in nourishment.

There is no one definition of 'healthy literature'—it varies from writer to writer, from critic to critic—but people often mischaracterise the 'chanachur' metaphor as an attack on commercial writers. Commercially successful books don't have to be regarded as junk food or 'unhealthy literature' because of their easily digestible content or if they are light on intellectual discourse. Sofa has always been vocal about politics; his main concern was with Ahmed's lack of interest in participating in social discourse. He played safe with his writing, according to Sofa.

Humayun Ahmed's influence in mainstream literature is undeniable—even my work was considered by many as an imitation of his writing, and I was thought to be someone who didn't have any vision of my own but had the ability to copy mercilessly. The blame game broke me into a thousand pieces and made me want to quit writing. I almost did, but thankfully, reading the work of Jahir Raihan helped me to get rid of the 'Humayun Influence'. The transition went horribly, and an identity crisis emerged that shone bright and proud—as if I hadn't suffered enough!

For a writer, creating a style of their own is important, but they also have to suffer from an identity crisis and solve the puzzle of finding a unique voice and style so that a comprehensive structure can lead in the future to growth and consistency. Many mainstream writers in Bangladesh don't follow any kind of structure—they consciously and unconsciously learned to follow Humayun Ahmed's style, so it isn't entirely their fault. Being accused of copying Humayun made me want to create something of my own, something that wouldn't be considered mainstream, but nor would it be too out of the box. I wanted to reflect on realism.

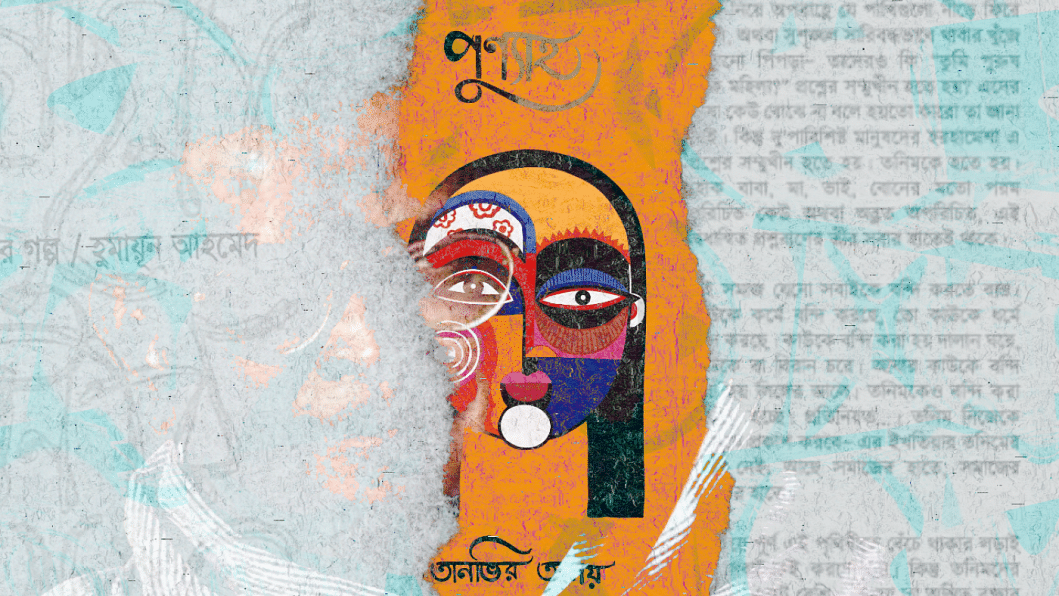

Back in 2015, when I first started writing Punyaho (Boobook, 2021), the plot was very plain and conventional. The pattern could have been found in thousands of novels, films, or TV shows, so somewhere along the experience of writing that first draft, I lost the battle to make myself recognisable as a writer. Tired of being considered a puppet and a shadow of other authors, finally, with a little bit of courage, in 2020, I reopened the unfinished manuscript.

Honestly, I felt disappointed at witnessing the half-baked, stereotypical depiction of characters who seemed like superficial imitations of other characters from more well-known Bangla novels. Authenticity plays a crucial role in cultivating a narrative. And so, with rage, I approached the reconstruction of my characters, especially the women, based on my current understanding, knowledge, as well my own identity. I worked with stream of consciousness, starting the novel somewhere in the middle of the characters' lives and ending, again, somewhere in the middle of life's journey. I chose to tell the story of a particular timeline—the canvas small, but the colors intense. As a student of literature, I absolutely love stream of consciousness for the way it breaks the conventional structure of written language with incomplete thoughts, unusual syntax, and rough grammar. Punyaho, my debut novel, is a result of my love for this narrative mode, and I'm not apologetic about it because I am tired of the rhetoric elitism practised so often in the world of Bangla literature.

As a work of social drama, I tried to make Punyaho a departure from the usual representation of women in Bangla literature. Most male novelists don't pay a lot of dedication to creating women characters, because as creators, they create what they perceive, what they encounter and desire.

As a writer, I believe my growth should draw from the political, social, and economic scenario of the region I am involved in. There is no growth without understanding politics. Writing Punyaho gave me the strength to celebrate the real women I have encountered, admired, and observed, who I believe deserved to be seen and portrayed in realistic ways.

Despite our best efforts, young writers are not widely accepted or celebrated because the publication market, especially in Bangladesh, is driven by names that are relevant. There is no space for a young writer who wants to keep up with the economic dynamics; cruel reality often forces them to change their style. I have observed the book market in Bangladesh for years, and I honestly didn't have the courage to face it, because rejection is not only barbaric but it also crushes one's spirit of fighting back. Although failure is an essential part of life, new writers should mentally prepare themselves to take these chances. I took a huge chance, and my experience since publishing my two novels, Punyaho and Durdhoy, has been marked by both positive and negative feelings.

Elitism in Bangla literature is nothing new—it is an ongoing ritual. I created something which might not be as tasty as chanachur, but it isn't as bad as burnt khichuri either! Somewhere in the middle lies a tiny sense of cohesion.

Tanveer Anoy is an author, archivist, and activist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments