Leafing through this life

This century had started 14 years ago—and unlike the previous one—the world was not drafting 19-year-olds to a great war so that they could die in the trenches. The world had grown much crueller; it did not intend on giving this odd bloke a clue, what this life was all about.

Here begins the story—a strange boy walked into town one day with his stocky pants and a scraggy stubble.

His quaint upbringing in the northern districts gave him little idea what to expect. The childhood days—all seemed like a blur; a long stretch of dupurbela: a Bangali summer afternoon in the suburbs that is often disturbed by the screeching of crows, and the snoring of the not-so-sweet neighbour.

This was a world where the adults either took their afternoon naps or were at work—which gave our guy ample time to read what his heart desired and what his hands could find. The dusty old bookshelf still towered over his seemingly miniature figure and he could only read what his height allowed his hands to grab. The random assortment of books in that wooden shelf would inadvertently go on to define his taste in authors, genres, and books in general for the rest of his reading life.

Little did his boyish innocence know, the stagnant suburban air could only do so much for his blossoming heart which wanted to read the world.

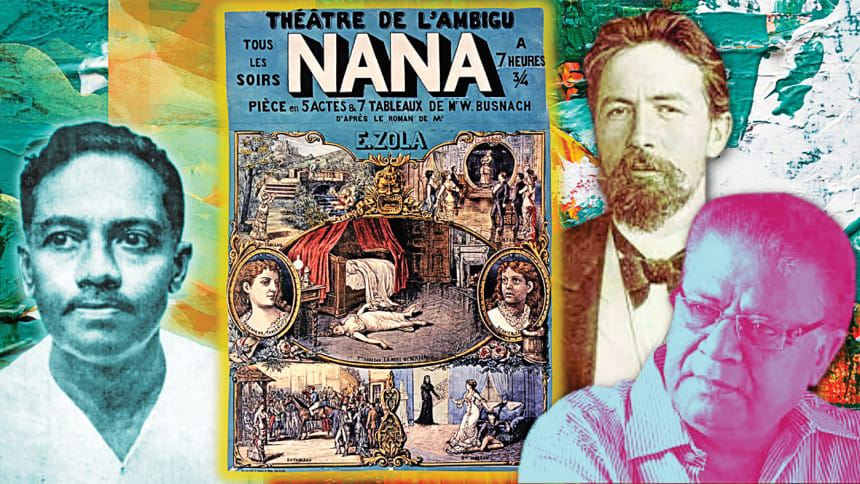

One afternoon, he found an old tattered copy of a novel. It was a Soviet era Bengali translation of Émile Zola's Nana (1880), a realist portrayal of an escort in decadent Paris. Not many adults would regard this as appropriate reading material for a 13-year-old, but such was the benevolence of the Bangali dupurbela—only its permissive generosity prevailed that afternoon and not the prying and poking noses of the adults.

It was not just indulging in the forbidden that the boy felt that afternoon. Zola tore apart the society's mask of progress and brought its hypocrisy out in the open for the world to see. Our young reader who was uninitiated to the realities of life was overwhelmed. But what else could he do? Reading was the only life that he knew.

Could he not have picked up a book that was more suited to his age? He hadn't learnt yet that books had any tags with them—that of age, ideas and ideology, passion and necessity. His household had no shortage of books. But this labelling or categorisation of books as children's stories and young adult novels, the dwindling drama and debate regarding genre and literary fiction, the seriousness and anti-seriousness of the business of reading—hadn't polluted his mind yet.

He only knew reading, merely reading. If growing up entailed relinquishing our innocence, he was stepping into it in stages.

The Zola novel stunned the reader in him. This was literature telling him to get out there in the world. There were worlds beyond his comprehension. There were lives to see in this world, a life to be lived on his own, and to feel life through compassion and empathy.

A few years had passed. He had grown a little, albeit mostly in stature, since the day he encountered Zola. He could finally reach the Chekov and Samaresh from the top shelf. But the pleasant and tranquil afternoons no longer possessed him. There was a nor'wester brewing in his heart which dared to disturb the dupurbela of yore.

The joy of stumbling upon a book at the library or from an acquaintance had become less a reality and more a reminiscence. Not returning a book on Greek tragedy from a distant cousin in seventh grade was a memory still quite fresh. So was his first encounter with Jibanananda Das from an anthology he had received as a birthday gift.

The years of his flesh were betraying him. His loyalty to a life of reading was dwindling and it terrified him. What would he be without it? He knew little of what was happening to him. His younger self had buried his nose in old magazines and rigorously bound local hardcovers instead of making friends at school and playing till maghrib with neighbourhood peers. Social life was something he had only read in the pages of the witty Wilde and the towering Tolstoy.

One day he was amused to find something growing in him that he had only read and cherished from afar. The spectrum of emotions and pathos sketched in Rabindranath Tagore's Golpo Guccho (1307) was what he had regarded as life's essence. But here he was—showing the audacity to make presumptions about life instead of choosing to embrace it. He had little choice but to stand trial for his foolish attempt at a proxy life, that in reading.

And who am I kidding? You might be quite irked at me by now, for what might come off as a nonsensical third-person rendering of my own life. I needed to distance myself from this past not out of shame—I loved and still do love to read but because this is painful. I was just like any other awkward teen who was not well prepared for a transition to adult life with its caricatures of social, personal and many other domains that I still find baffling.

And this was what my life felt like when I moved to Dhaka in 2014 and became that odd stranger who was new in town.

The urban landscape in Dhaka tried its best to suffocate me and I was beginning to lose my hold over structures that held life together. I was spiritually shaken and at that time could only hold on to very few things. I had merely switched delusions— from mistakenly trying to find an aesthetic exegesis to life from Tagore's short stories and poems to desperately hanging on to Tagore like a raft; the Tagore of Geetanjali, pujo-porber-gaan and the crisp yet idyllic prose of his non-fiction. It wasn't the drowning that let me down but the fear of letting go of what was so dear to me. (Returning back to Tagore again and again is such an old and tiresome Bangali cliché but I don't think I can tell it honestly otherwise.)

So here I was all alone, drifting away on a raft in cold unknown waters. Studying, going out, dining out, making conversations while my heart only ached and it still does for a life in reading.

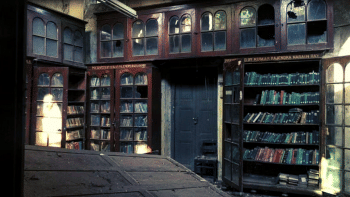

I would soon walk through the doors of a small bookstore in my neighbourhood. It was Charcha. I was so shocked that something so stupendous could exist so close to my place. It would soon become my second family. Charcha became a place where the reader in me found a home. I was free from the anxieties that had haunted me till then. I didn't have to compromise or struggle to make space for the reader in me. He existed at ease there, as though it was in its natural habitat. It was my family, it showed me that social life didn't have to be divorced from a life immersed in books. I made friends for life in Charcha among fellow readers. Prioritising to read above everything, came with a sacrifice, I had always thought. I had prepared myself to give up on things to read. This Elysian bookstore showed me that the reader in me too could embrace the many parables of life.

Charcha doesn't exist anymore. And the wound is still quite fresh though it's been a few years since it closed its doors. When I began writing this piece, it was supposed to be about Charcha but it feels too soon to broach a subject that's so tender. I ended up writing about who I was when I walked through its doors instead.

The writer Mario Vargas Llosa in an interview for The Paris Review stated how he needed some space and time apart from a subject before he could write about it. I can now understand what he meant.

So, the stranger did indeed walk into a bookstore in town but that story is yet to be told. That life probably is yet to be lived.

Mursalin Mosaddeque grew up in the suburban town of Rangpur and he can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments