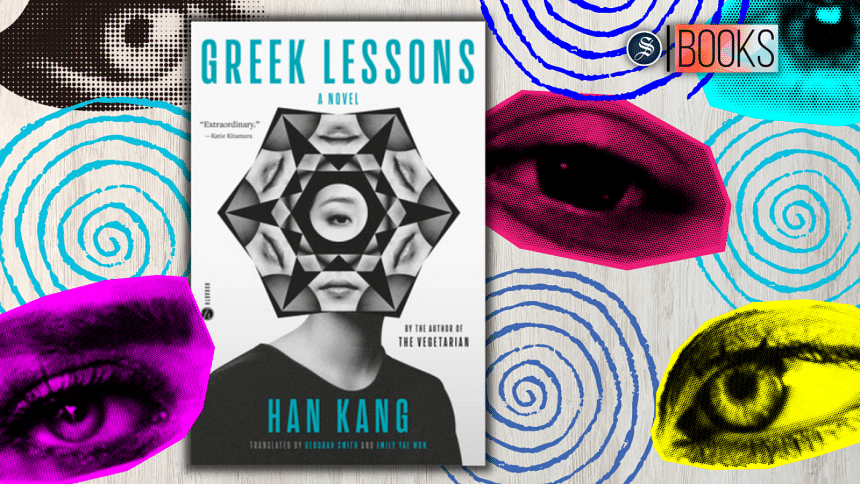

Of losses and languages: reviewing Han Kang’s 'Greek Lessons'

During a poetry workshop last year, I was trying to write a clean poem, bereft of any blubber. The discussion steered along the lines of the Imagist movement: "Write in distilled images and let go of any sort of excess"— I recall the instructions given to us in a sonorous demeanor. At that instant, the image I wanted my poem to hover upon was—a tangerine in a wicker basket, painted white.

The manner in which certain objects, colors, words grab and keep our attention for moments at a stretch and urge us to write about them, as if being sentient, is quite wondrous to think about. For me, the obsession with the fruit began with continuous viewings of Magritte's works on Instagram art pages and ended with flickers of it dispersed in most of my writings, appearing in phrases such as "citrusy smells" and "lemony shades".

Han Kang in a succinct paragraph in Greek Lessons (2023, Hogarth) translated by Deborah Smith and Emily Yee breaks down this moment of being enchanted by a certain image (a tangerine followed by a tree) by writing the following:

"Let's stop at the market and buy tangerines," she heard her mother say. She had been struggling to zip up her coat, but at these words, bright orange tangerines appeared before her eyes. She was amazed they weren't real, that she wasn't actually seeing them, when they looked so delicious. She hurriedly thought of something else— trees— but the same thing happened. It was like magic. In front of her lay only the darkening alleyway and the seemingly endless stretch of concrete wall, and yet she was quite clearly looking at a tree. The shapes of letters she'd only just learned began to superimpose themselves over the tree. 나무. Saying the word out loud, she laughed to herself. Namu. Namu. Tree.

Everything in this paragraph—starting from the tangerine appearing as an unavoidable figure in front of the character's eyes, to the superimposition of the letter meaning "tree" with the image of trees in place of a concrete wall—makes one think of the webbed nature of language and how our memories to language are pinned down through strands of associations with images. This is one of the many ways in which Kang masterfully dissects the language's multitudinous nature in Greek Lessons, so much so that, the central crux or the third protagonist, on which the story is hinged upon is language itself.

Greek Lessons is a meditative yet visceral, painful yet tender addition to the anglophone reader's diet. Kang, through novels like The Vegetarian (2007) and Human Acts (2014), has proven herself to be an expert at depicting a kind of violence that is reminiscent of Flannery O'Connor's, in its dull ferocity. Here it seems to take a back seat. There is violence here too, but that of a subtler kind, one which manifests itself at a larger magnitude —through the intrusion of cruel happenings in the lives of the protagonists. The novel faintly traces out two lives that meet in a classroom at Seoul: an ancient-Greek teacher in his late 30s who is gradually losing his eyesight, and his student, a young woman who has recently lost the ability to speak and going through an exhaustive custody battle over her son, followed by the death of her mother.

The novel unfolds through a series of letters and soliloquies that illuminates the teacher's story. He relives his memories with a susurrating desperation, emphasizing on the last remnants of visual delights, melting into fantasies imprinted on his memories: the faces of relatives, trees undulating into a pale single whole, dainty cigarettes, and sways of green and red temple lanterns. It is in these pages where we find Kang's undiluted poetic genius dressing the narrative with stunning visual imagery, almost cinematic in its scope. As the other focal point, the student's chapters are written in a removed third person. They disclose in short scenes of remembrances, a severely wounded individual trying to access expression again, being unable to speak. The prose Kang positions, at once redolent and cryptic, complements her characters' inward alienation.

There is an aspect of the "physical" and tangible, in relation to language, letters, or the act of speaking spread throughout the novella. To start with, we find several instances where Kang gives us a tingling simile, comparing the sleek streaks of Hangul alphabets to "stridulating insects". Similarly, conveying a sense of warm humor, one of the two protagonists in the text gives kinetic lives to various letters from different alphabets while writing a poem, which compares the curves of "the small "a'' of the roman alphabet" to an exhausted person, the "Hanja for "light," 光, gwang," to a shrub rooting down" and the "echoic 우우우, woo-oo-oo," to "a row of raindrops along a window ledge". I was pleasantly reminded of Amit Chaudhuri's whimsical notes on the Bangla Bornomala, calling "ম" a dancer adrift and "প" an aged man. My travel notes to Karnataka compared the whorls of Kannada letters to inverted cow udders and jasmine flowers coiled up.

While writing of the first time the woman begins losing her ability to speak, at the age of sixteen, Kang expresses how language and the act of speaking is a mode of touch, or something "unbearably alive" in its own right. Echoing the voluptuous, visceral style in her acclaimed novel The Vegetarian, Kang writes: "The most agonizing thing was how horrifyingly distinct the words sounded when she opened her mouth and pushed them out one by one. What she longs to express, are not feelings and ideas, but rather the sensuality of speech as it travels through the body." The character marvels at how language and utterance "moves lungs and throat and tongue and lips, it vibrates the air as it flies to the listener."

Plot wise too, language and specifically Ancient Greek plays a seminal role in the romance of the two focal characters. Why the woman is taking up Greek lessons is not made clear but readers are hinted that she has a certain facility, a fascination towards language, that she is taking up these exercises "to reclaim language of her own volition," that it is not the content of these ancient scripts which draws her but the internal structures—the complex plays of grammar and syntax. On the other end of the romance, we have the teacher striving for the excellence of the deceased language, having a sense of mystification towards it, something academics are not a stranger to.

There is a certain obscure quality to Kang's writing in this text. Although she has a meticulous penchant for describing her characters' psyches through clean sentences in which unforeseen images erupt—there is an insistence on indeterminacy. The readers end up becoming witness to a sweep of incidents, layered with beautifully resonant poetic details, in the lives of the protagonists but never quite getting the grasp of it, with bits being left out for interpretation—the refuge the teacher seeks in Ancient Greek being one of them. It gives us an insight on his deeply melancholic self though, when he comes to the conclusion that the reason why he is so drawn to the language is because it is dead.

This obscure quality also touches the portrayal of the two protagonists intertwined in the narrative. In one scene, the woman finds herself in a conversation with her son. She suggests he come up with names for themselves "based on what natural thing they most likely resembled". While he called himself the "Sparkling forest" he gave his mother the name of "Thickly Falling Snow's Sorrow". This bit along with the literal image that we have of her, clad in a black layer of clothing and the teacher's musing about how someone alive could be so quiet— draws up a hazy sketch of desolation and dejection in a human form.

Terry Eagleton in his essay, "Character" discusses how "one of the most common ways to overlook the literariness of a play or a novel is to treat its characters as though they were actual people" is to imagine them as corporeal beings not set to the tone and mood of the text but to the whims and moral contexts of our reality. Kang's unnamed protagonists might come off as underdeveloped. They are engraved with a lot of heart in them, an exercise in emotional realism some would say, but are somewhat misty around the edges, making them to be less of a character and more of a cesspool of their losses, both in terms of physicality (his debilitating eyesight and her inability to speak) and in the realm of the personal and personal (his heartbreak, the death of her mother and the losing the custody of her son). At an instant, it is even spelled out by the woman who thinks to herself about how she does not feel like a real person but takes the shape of whatever she is consuming at that moment, but how "she knows that she is neither rice nor water, but some harsh, solid substance that will never commingle with any being, living or otherwise."

Abiding to Eagleton's logic however, Kang's creations, be they metaphorical or realistic, fit right into the mold or rather creates the melancholic mold of the universe in which they are set. There is a sense of inexorable catharsis, and dare I say— spirituality—when the protagonists begin their journey into one another since they alone embody the ideas and predicaments of the text.

At the end, both characters have been touched and affected by one another; by their reciprocation with their own recollections, their sensations and conceptions; by the passage of time and a shared space and by the expression and non-expression of language. As the curtain closes followed by hermetic, haiku-like ruminations and a white silence gradually spreads across the pages— the protagonists are found to be conversing verbally and non-verbally in their shared landscape. We feel our cue to leave.

Jahanara Tariq is a writer from Dhaka, Bangladesh. She is currently employed as an adjunct faculty at the Department of English and Modern Languages at Independent University, Bangladesh (IUB).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments