Memory is a treacherous and wonderful thing

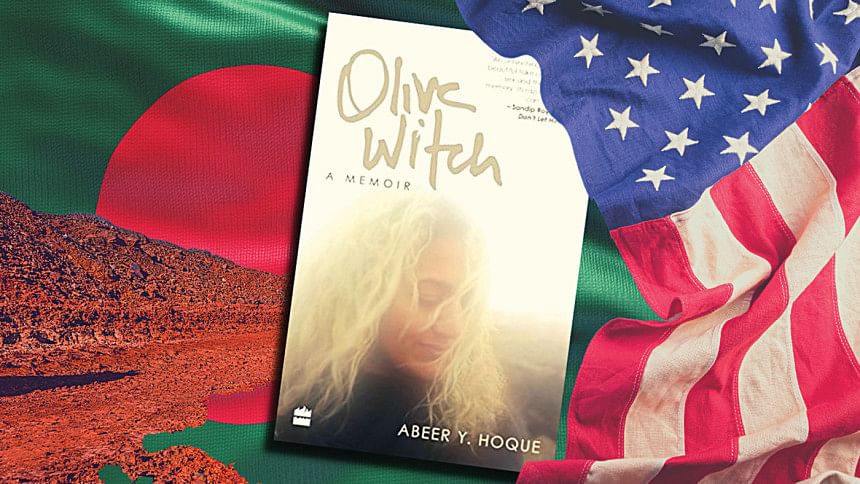

Around 14 years ago, I left my life behind in Nigeria. After almost half a decade spent in a land far from home, leaving felt crushing. While my memory of that time is fuzzy, some emotions tend to resurface now and then—the red dust, the bright sun, and so much laughter. Trying to create homes across continents is never a good idea. After a while, no place seems to smell of home. And yet, the belonging one searches for lies within. Abeer Y. Hoque stated this in a discussion with Nupu Press not very long ago. In her book Olive Witch, we see that journey manifested across a length of time whose size is only bested by the sheer geography it covers. From a childhood in Nigeria to spending breaks in Bangladesh, to growing up in New York, and then returning to Bangladesh—the memoir covers the enormous, and multifaceted life of Abeer Y. Hoque in lyrical, almost poetic, prose.

The memoir is split into three parts, each describing her life in different parts of the world. In between the essays written in the first person, Hoque includes interlude chapters in the third person, describing a part of her life where perhaps everything changed for her. A time when she woke up with charcoal in her mouth, confused and uneasy. These are messy passages, filled with conversations and poems, reflecting her time in a psychiatric ward after a failed attempt at taking her own life. Hoque does not linger on in these chapters— they are short by nature— but allows these passages and poems to serve as a peek into her mind.

Aside from the interludes, the other thing that stands out is the opening of every chapter. With every title comes a small poem, sometimes a regional piece, and the weather. We start our journey in Nigeria, in the university town of Nsukka, where the land is dry, and everything is coated in red dust.

As a child, Hoque finds herself exposed to a world that inevitably marks her as other—owing to her skin—and yet it is still a place she comes to call home. It is the only place she has known as home, spending so much time poring through books or playing in the bright afternoons with friends—many of whom were immigrants. It was a scenery I was personally quite familiar with. The scent of the afternoons, the stern voices of the teachers, and their particular accents all came flooding back to me as I was reminded of a place I once knew as home, short-lived though it was.

And yet, it is only in the following section that the book really stuck with me. During her time in the US, we saw Hoque in some of her most volatile moments. Hoque's words felt angrier, more pained, more confused, and more distraught than ever. The shock that comes with changing your entire life, packing yourself up in a few boxes, and moving to a place where no one knows or likes you—all of it seemed to upend much of her sense of self. Schooling felt different, the leering gazes of her schoolmates stuck to her, and her bond between her parents and her sister grew increasingly strained. This is around the time of her adolescence, a time of love, and of discovery.

Then there was the endless barrage of expectations, all of which Hoque dissociated from, but struggled to voice, which eventually leads us to the final section of the book: her time in Bangladesh. This is the part where a journey most tumultuous begins to find some respite. The chapters here are perhaps the most lyrical: we see Abeer Hoque, the poet, in full bloom. After an uncomfortable phase where she drops out of her doctorate program and finds her way out of the psych ward, we reach what may be described as the finale of a journey of self-actualisation. But in truth, it is also a beginning.

We move in and out of events in her life, with the central theme of belonging connecting it all. The search for home encapsulates the journey of this memoir, but it is in the grittier details of the journey that we see her life in full bloom. Hoque is, at times, stubborn, loving, powerful, fragile, and sometimes she is all of these things at once. Wounded though many of these stories feel, I cannot help but see a certain sense of celebration in all of it. Hoque's love for every place she has had to call home, despite it never truly being so, and her love for everyone she has known, is what makes her journey so deeply moving.

Raian Abedin entertains the idea that no words are ever read the same way they are written.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments