‘Nil Chhaya’ reconjures ghosts of Bengal’s Indigo Revolution

Time, as we will see in this play, works in very interesting ways. In March 1859, Indian peasant farmers (ryots) of Bengal and Bihar unanimously refused to keep being exploited by the British planters of indigo crops. In 1860 in Dhaka, Bengali playwright Dinabandhu Mitra anonymously published Nil Darpan, a play that bared the British planters' cruelties, the hypocrisies that triggered those farmers into the Revolt. On September 8-10, 2022, Dhaka's Bangladesh Mahila Samity auditorium staged Ben Musgrave's 'Nil Chhaya' (The Indigo Giant), translated from the English and produced by author Leesa Gazi—a play that connects the Indigo Revolt to the oppressions faced by present day garment factory workers in Bangladesh. And here I am, nearing the end of September, writing about the play two weeks after its curtains closed.

Time is evasive, persuasive, repetitive. Effective. In between the events I've recounted above, time swirled and coalesced into impressions, into action.

In Musgrave's play, directed by Naila Azad, time is an omniscient narrator—one whom the script refers to as 'The Presence'. The Presence (played by Dr. Sydur Rahman Lipon) knows that the denim factory in which Rupa works rests atop land that once held a 'Nil Kuthi', an indigo factory. But he isn't the only one who remembers.

Rupa (Qazi Nawshaba Ahmed) remembers, though she doesn't yet know what she recalls. The Indigo Giants remember, as they hover over the land in their ghostly, Klansmen-like avatar, representing the powerful but ultimately defeatable White Man. The land, haunted, remembers. And so do the books lying dormant in the vicinity—records that store proof of how the farmers in 1858-9 were oppressed, forced to cultivate indigo in place of rice crops that would feed them, blackmailed into signing legal contracts and accepting advances, punished in court for breaking the contracts they had unwittingly signed, drowning themselves in debt. As many as five million people died in the Indigo Revolt before the Indigo Commission, formed in 1860, would investigate the cultivation systems' practices.

'Nil Chhaya', produced by the UK-based Komola Collective with support from GCRF QR Rapid Response Scheme, the British Council, the University of East Anglia, The Charles Wallace Bangladesh Trust and Living Blue, attempts to engage "in dialogue" with Nil Darpan. It does this by revisiting the peasant community of Mitra's historic play and dedicating half of its story to that of a simple family—farmer Sadhu (MS Rana) and his wife Kshetromoni (Qazi Nawshaba Ahmed)—whose lives are utterly destroyed by the whims of a British indigo planter, Robert Rose (Sharif Siraj). Rose's passions make currency, an object to be bartered, out of Kshetromoni in the name of 'love'; the system he represents robs Sadhu of his dignity, his freedom, and—as he refuses to sign the forced contract—his life.

Meanwhile, taking place in the present day, the remaining half of 'Nil Chhaya' shows local denim manufacturers who work on this same land. They are advised by cheerful foreign buyers to "be cheap", which means to make peace with the poor pay, cruel working conditions, the immense damage to their mental health, and threats to unionisation if their country is to benefit from the possibilities of a thriving RMG sector. In the background, debris from the denim manufacturing process bleeds copiously into the river, while its demands kill an indebted, overworked factory worker named Mina (Mitali Das).

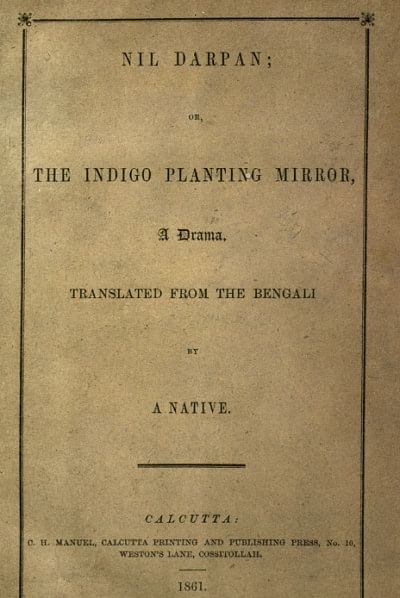

"A poor man's word bears fruit after the lapse of years", the Sadhu of Nil Darpan says in its first scene. The afterlife of Mitra's play manifested this reality—with Michael Madhusudan Dutt translating it to English, it was edited and sent for publication by James Long, 500 copies printed by the Calcutta Printing and Publishing Press and distributed, revealing the exploitative practices of the British crown and East India Company. Long and the book's printers faced vengeful propaganda, and prosecution in court.

In a similarly literal way, 'Nil Chhaya' manifested Sadhu's line after the play closed in theatre, when team Indigo Giant performed extracts in Rangpur and engaged in discussions with indigo farmers and artisans about the history and potential revival of indigo cultivation in Bangladesh.

But in literary terms, the play gives Mitra's opening line magical realist powers. Wood apples, born of the trees of the land and used as weapons in the Indigo Revolt, empower both Rupa and Kshetromoni into playing crucial roles in the play's climax. Both characters are incited by the impact left by other women: by Mina, who died in the factory and by Nabina (Mitali Das), who is gathering forces for the Bengali Renaissance. With a mutiny brewing in the background, the play thus transforms its women from objects and recipients of action into catalysts of it. Forget being shackled by social conventions; these women fly through the boundaries of time to bend, provoke, and rescue history. They render a future for the past.

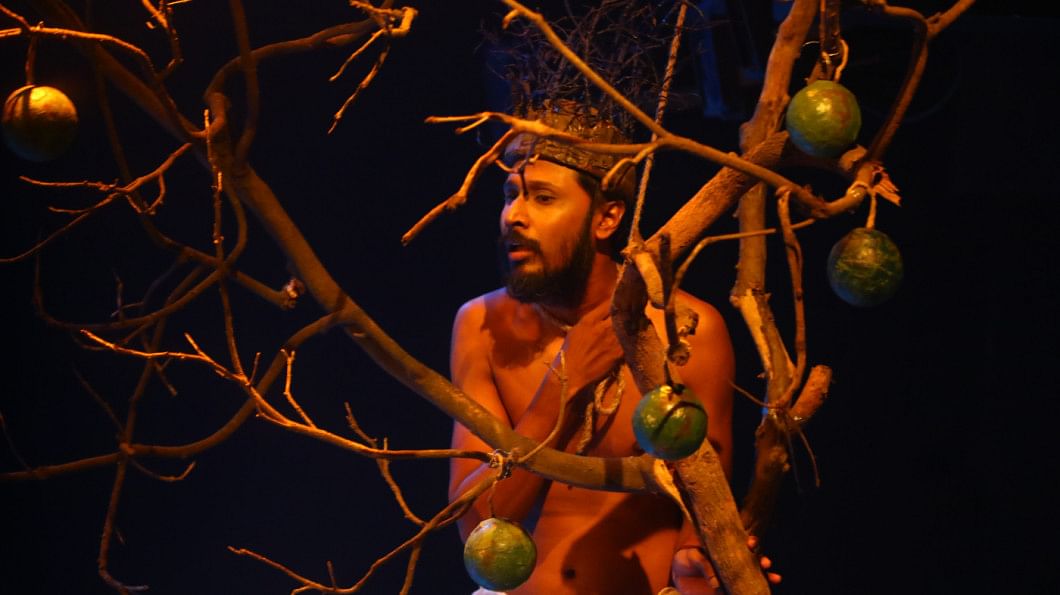

In one of the most haunting scenes of 'Nil Chhaya', Sadhu begs Rose not to enforce the sham contract on him. His family will starve if they have to devote 20 bighas of land to plant indigo. Rose picks up the clay figurines Sadhu's father used to collect and asks him to compare who is the more powerful of the two—The black man or the white? The (blue) Krishna or Shiva?

As Sadhu continues to refuse, Rose places a mound of mud on his head and plants, one by one, seeds of indigo on his scalp. The music in this scene, composed for the play by Shishir Rahaman and Naila Azad, reaches a thundering crescendo as Kshetromoni screams in horror, watching human dignity draining out of her husband's crouching form.

If this performance is indeed a dialogue between 'Nil Chhaya' and Nil Darpan, the message that emerges from it is that history leaves its traces, can impact the time that comes before and after it, and that it can repeat both its dips and swells as time goes on. The medium through which this message operates is by highlighting the power of the individual—one family's refusal, one woman's flight, one seed planted, and one missing signature from the book in which hundreds of other peasant families had signed over their lives to the British. All change begins with one spark.

Sarah Anjum Bari is the editor of Daily Star Books and Adjunct Lecturer of English at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB). Reach her at [email protected] and @wordsinteal on Instagram and Twitter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments