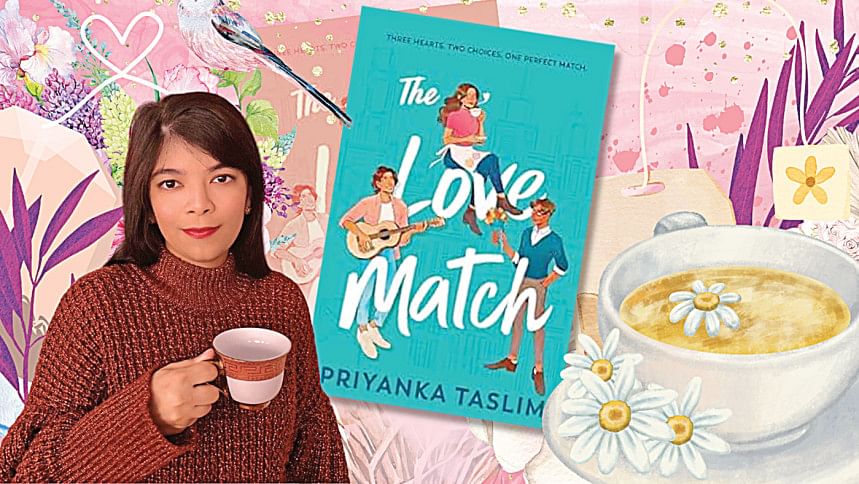

A perfect cup of literary ‘saa’

Priyanka Taslim greets me with a gentle smile as we meet over Zoom. She is eloquent and our conversation flows organically, akin to an adda over a cup of 'saa' (cha). Her debut novel, The Love Match (Simon and Schuster, 2023) has garnered praise in Teen Vogue, USA Today, Pop Culturalist and more. It was a Junior Library Guild gold standard selection and one of Amazon's best young adult novels of 2023. A starred Kirkus review called it 'candid, textured, and amusing: a novel readers will devour in one sitting.' Despite the recognition, she is grounded and connected to her roots. Her grace, simplicity and humility shines through her words. It's a pleasure to get to know her as a writer and as a person.

Can you describe your publishing journey as a Bangladeshi-American author debuting with a novel with a majority of South Asian characters?

It wasn't until I was an adult that I read a book by a Bangladeshi-American author, so even though I've always been a voracious reader and have long dreamed of being an author, I thought it was a futile hope. Seeing that book, The Gauntlet (Salaam Reads, 2017) by Karuna Riazi, rekindled some hope in me, and I finally began seriously pursuing publishing by completing a draft and seeking an agent. It took a long time to get from that point to The Love Match (TLM).

I set the book in Paterson where I grew up, and to be authentic to Paterson, there simply weren't a lot of white people around who didn't come in as educators, at least in my experience, so it felt like a good opportunity to explore a realistically diverse cast. I was pleasantly surprised when the book went to auction, but there were still many challenges.

I have definitely encountered some racism and othering from people who didn't like that there were so many cultural details and words left untranslated that readers are meant to glean from context. I also faced the opposing problem of readers who are so hungry for representation that they're wounded when the representation they get isn't exactly the same as their own experiences, even though there's so much diversity within any community.

Although I've sometimes wondered if I would get more overall support if I wrote something more "palatable", for the most part, though, I was fortunate to have a kind reception that I'm truly grateful for, and fortunate that publishers want more books from me.

TLM includes a host of Bangali characters including one who hails from Bangladesh. Was this a conscious choice to include one of the male protagonists from the motherland?

It was definitely intentional to have a male protagonist from the motherland. Because I'd already decided to have a mostly South Asian cast, I really wanted to showcase how different people within the same community could be depending on their individual circumstances, because in a lot of media where there's any South Asian representation, you have one token character, and they're most often Indian. I thought it would be a great opportunity to counteract stereotypes in subtle ways, since in the book you can see that Zahra resonates with Nayim's situation even though she's grown up in America. Nayim is also a musician and I don't think you often get to see enough creative South Asian representation that isn't the funny nerdy side character.

There's a popular trope among YA authors where brown protagonists tend to have white love interests. What made you deviate from this?

Honestly, just to veer away from the cliche of it all! As I mentioned, there were very few white people I knew while I was a kid in Paterson. It was only in college that I met more people of diverse backgrounds, including class. Paterson is mainly working class black and brown people, and there's a lot of diversity among them. There are many different diasporas. But my world was pretty insular when I was there. So it felt more realistic anyway, since I was writing a "love letter" to Paterson, to have predominantly working class Black and brown characters, which is what informed Zahra's friend group and love interests.

At the same time, I was a little tired of the "white guy frees the brown heroine from her backward culture" trope that you see a lot in media about Desi/Muslim diaspora characters. In fact, the idea of saving the protagonist is explored quite a bit, because Zahra hates the thought of people trying to do that just because her circumstances are challenging. I wanted her to have a little more agency.

I also feel like one of the appeals of the white love interest is the forbidden romance aspect because so many parents in our communities prefer their children date/marry within the community. On the other hand, this feels flat and lazy to me, because it ignores when relationships are not approved of on the basis of, for example, caste.

Bangladeshi Muslims do not have the same concept of caste that Hindus do, but the past absolutely bleeds into marriage conversations, because I've heard "so and so isn't from as good a family even if he himself is working a good job, has an education, etc." I find the notion very silly and thought a young woman with modern sensibilities like Zahra would too, so I wanted to explore that struggle with her own romances. Harun is somewhat suitable because he's wealthy, but he's "new money" and his family doesn't have as good a lineage as her. That's why their respective mothers want to set them up, because they feel each of their families gain something from the match.

Harun's family, the Emons, lift their social standing, while Zahra's has more financial security—but to two Bangladeshi-American teens, this is very bizarre. Then you have Nayim, who is an orphan and working as a dishwasher, so even if he's still also Bangladeshi, Zahra's mom disapproves. She only wants a guy who will give her daughter upward social mobility. I think that kind of "forbidden romance" is more interesting.

Even when interracial romances are written, because I'd be interested in writing one someday, personally, I'd love to see more without a white love interest. Elders in the South Asian community often have biases against other groups, or vice versa—it would be interesting if that was navigated more often rather than the typical white/brown dynamic, even if I've loved plenty of books with that sort of relationship.

There's a generous usage of Sylheti words and phrases in the novel. What was the reaction of your publisher regarding the use of the dialect without a glossary at the end of the book?

My publisher was lovely about it and didn't ever police me when it came to those things! I don't think they ever even brought up a glossary, though they once asked me about my italicizing preferences. I did have some trouble during the copyedits stage, because the Sylheti dialect isn't the standard Bangla that you can easily Google and is practically its own language sometimes.

I got more pushback from certain readers, which I had already been bracing myself for but was still a little disappointed and surprised by, since I hadn't encountered those issues with my publishing team. It's funny because none of my team was Bengali either, so I relied on them to step in when I couldn't see the forest for the trees and have me clarify anything that confused them, but certain readers were upset I didn't translate everything.

I genuinely tried to ensure that things were apparent through context, because as an English teacher, I often taught students how to dissect historical texts or classics set in Europe even if they weren't familiar with every detail they encountered, but unfortunately, as soon as it's a book by an author of colour, people lose the courtesy they'd extend to authors like Dostoyevski or Victor Hugo. I hope that changes someday. Despite this, though, I do generally feel most of my readers of all backgrounds tried to engage with the text respectfully.

Humour is one of your strengths as a writer and this is clearly evident in TLM. How difficult or easy is it for you to write humour?

I am also an English teacher and studied literature (as well as literary writing) so sometimes I find myself taking my work a little too seriously even though I think I'm a generally funny person to those who know me. Usually, this means I then have to edit my work in future drafts to add more situational comedy and banter, which is a lot of fun! But I struggle at first because I initially think about things like character conflicts and struggles, before trying to hone their voices and quirks and humour in later revisions.

How has TLM been met within the South Asian community in New Jersey where you grew up?

I kept the fact that I was a writer close to my chest until TLM got closer to release (in part, because uncles and aunties really struggle with preordering things online, haha), so I was pleasantly surprised by how lovely my local community has been. I had a lot of family friends at my New Jersey launch event, have been invited to several schools and libraries that have large Bangladeshi student populations, and even just got invited to be a panelist at a Bangla literary fair in NYC later this year, so I've been very blessed by the reception. Not everyone in the community will necessarily read the book, because like my parents, they might struggle with that much English, but there's a lot of enthusiasm that I am Bangladeshi and writing about Bangladeshi characters.

There are diverging views relating to the inclusion of LGBTQ characters and the non-inclusion of 'halal' romance in TLM. What is your take on this?

I grew up in the US but obviously have a lot of love for my faith and culture. I never set out to write a book about religion or religious characters, but a book where they just happen to be Muslim simply because the majority of the Bangladeshi (and Pakistani) community is Muslim. In spite of this, I made sure to include characters that are close to perfectly practicing and are empowered by their religion, like Zahra's friend Dalia, because like I mentioned earlier, I wanted to take advantage of my mostly South Asian and Muslim cast to explore diversity within a community, since in a lot of media, South Asian characters are flattened and tokenized.

Growing up in a place like Paterson, I saw the diversity of the Bangladeshi and the Muslim community with my own eyes. I was very sheltered by my parents, ironically, but I knew a lot of girls in my classes who were Bangladeshi and/or Muslim and dated around—and a lot of boys who courted them. Some are now married to those boys they snuck around with. Even as a teacher in a school district that had many Bangladeshi students, I overheard quite a bit of flirting, especially when students didn't realize I was Bangladeshi too.

Some people wouldn't like to hear this, but I personally know plenty of LGBT Bangladeshi Muslims and LGBT Muslims of other backgrounds. Their levels of practice may vary, but they exist, and while they experience hardship, not every South Asian or Muslim family disowns or abuses their children. I wanted to explore some of this nuance with two characters who are twins, one being a pious hijabi girl and the other being a lesbian. Since they're side characters, I didn't want to focus overtly on the day to day struggles of those nuances either, but had them as part of their backstory. Not everyone is like me, but I wouldn't be able to disavow a loved one for something they can't change like their sexuality, and I am disappointed that some readers essentially get angry when any representation that isn't a perfect Muslim exists, because as a teacher of young adults of all sorts of backgrounds, I want everyone to feel welcome in my work.

I think it's perfectly fine to hold yourself to a certain standard and want a specific kind of representation, but not necessarily to undermine others' experiences for not aligning to your expectations. It would be different if I was marketing the book as being about religion or religious characters, but I predominantly focused on culture, not faith.

I do hope the readers who didn't resonate with my work find the representation they crave, but I don't think it's fair for them to feel entitled to policing anyone else's work unless it's problematic, and to me, characters who love their identities even if they don't perfectly conform to certain societal standards are not problematic. Those readers can read other authors who hopefully give them what they need and I'm okay with that! I have plenty of people who DO identify with the character of Dani and reach out to me to thank me for being inclusive, or Muslim readers who resonate with other aspects of my work, and I feel fulfilled knowing that what I write means something to a bigger number of people than I ever could have expected as a little Bengali girl with her nose in a book back in Paterson. South Asians of other backgrounds, other kinds of readers of colour, and also white readers reached out to me with positive feedback too. You just can't appeal to everybody, so I try to carve out my niche.

Do you read Bangla fiction or poetry? Any favourites?

I grew up with my parents reciting a lot of popular poems to us, particularly at bedtime. Rabindranath Tagore was very common, but also Kazi Nazrul Islam. When I got older, I read a book of Tagore translations (short stories and poems) and found his work very beautiful in English too, which is why he's referenced in the book (Harun's bearded dragon). He's more known internationally—I love seeing him anytime I'm at Barnes & Noble—but other Bangla poets whose translations I've managed to find have such poignant works too. I'd love to read more translations. I've also read Bengali/Bangladeshi diaspora novelists like Jhumpa Lahiri, Adiba Jaigirdar, Anika Hussein, Karuna Riazi—really, any I can find, I put on my reading list. It makes me so happy to see more and more. My exposure to translated Bengali fiction was sadly limited for most of my life, but I seek it myself now, and I also hope that authors in Bangladesh who want to publish for a western audience find success. All kinds of representation is so necessary and important.

Any advice you'd like to provide to emerging writers especially in Bangladesh?

If there's one thing I hope Bangladeshi writers take away from my experience, it's that there's a hunger for Bangladeshi characters with all sorts of experiences. There's a readership out there for you, so don't count yourself out because of your identity or because you're not American. I actually have a book in the works set in Bangladesh. It's from the perspective of a diaspora character like me, of course, but if I can tell that story, then I hope that means you can also write books set in the motherland, books with Bangladeshi casts, etc. I also think people are becoming more open and curious about the world around them, which is why we see the growing popularity of not just media about diaspora identities, but of subtitled international media—Korean and Chinese dramas, Bollywood movies, Japanese anime, popular streamed series where English is hardly ever spoken. I think that will only continue to be true and to grow. At least, that's my hope, so please don't give up before you've even tried.

Nabilah Khan was born and raised in Bangladesh and currently resides in Sydney, Australia. After more than a decade working in the global banking and financial services industry, she now works in the Australian public service.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments