Songs of our soil: In praise of Mymensingh’s Bangla folk ballads

Folk-ballads are living archives that represent the imagination, values, ideas, and aesthetics of the people to whom they belong. Bangla literature has a rich repertoire of folk ballads. We are, however, quite oblivious of this treasure trove and, therefore, there is a dearth of research on these folk elements.

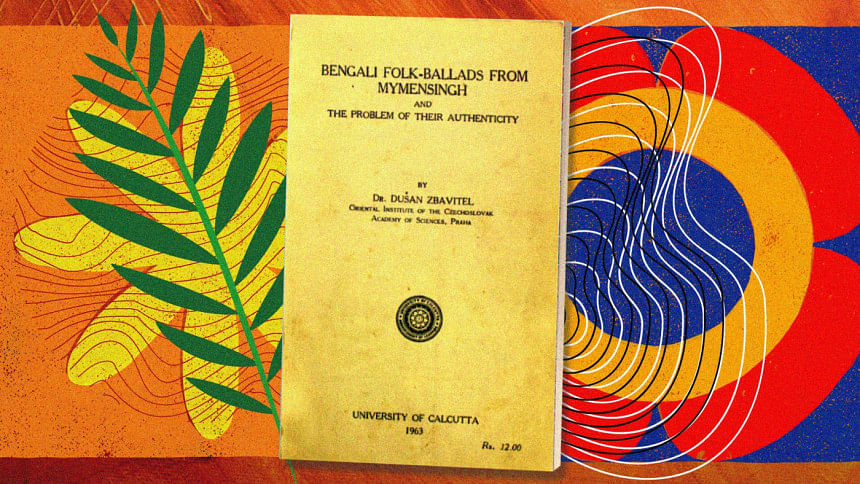

Czech Indologist Dusan Zbavitel's Bengali Folk-Ballads From Mymensingh And The Problem Of Their Authenticity can be called a wonderful exception in this regard. It is considered to be the first literary study of the beautiful folk-ballads from Mymensingh. The study was published by the University of Calcutta in 1963.

A brief background of the book may not be irrelevant here. In 1923, Rai Bahadur Dineshchandra Sen edited a volume of epic songs from the Mymensingh District of the then Eastern Bengal under the title Maimansimha-gitika. The ballads were mainly collected by Chandra Kumar De, a literary activist from the area. In the following years, Dineshchandra published three more volumes of balladic texts containing epic songs from different parts of Eastern Bengal. The beautiful ballads received enthusiastic response and admiration in India and abroad. However, for some scholars these ballads were too good, and they shared doubts about the antiquity, authenticity and folk character of these lores. Dusan Zbavitel found this uncertainty "highly regrettable" and undertook a study to assign to the ballads their proper place—"one of the high points of Bengali literature". Dr Zbavitel tried to find out: "what is it that makes them so excellent?"

Zbavitel confined his analysis to the study of the ballads originating in Mymensingh—41 ballads containing more than 21,000 verses. He took an arduous effort of analysing each of these 41 ballads to prove their originality and, I must say, he achieved his goal with marked success.

One key argument put forward by Zbavitel in favour of the originality of the gitikas from Mymensingh is that these ballads are not collected by a single person and, still, there are similarities among the ballads: identical images, and similar artistic approach and common inventory of similes and metaphors. So these ballads couldn't be the creation of a modern poet as suggested by some detractors.

According to Zbavitel, the most significant aspect of these folk ballads is that they are devoid of any religious implications. They generally show harmonious co-existence of the Hindu and Muslim communities, without religious bias on either side. Zbavitel points out the fact that most of the Hindu ballads were collected from Muslim singers, which shows, according to him, that these folk poems were enjoyed and appreciated by both the communities with the same eagerness. The secular outlook of the folk ballads is diametrically opposite to the explicit religious connotation of the classical Bangla literary texts such as Mangal-kavyas and Vaisnava literature.

Zbavitel extensively discusses the ideological and artistic approach of the ballad writers, verse and rhyme technique, and use of similes and metaphors in chapter three and four of the book. The most dominant motif, according to Zbavitel, is love. Even the historical and heroic epics can be grouped into this category.

As to the literary techniques, the ballad writers, being true to the characteristics of folk epics, do not try to introduce innovations in their lyrical dictions. They are content with the poetic means offered by their predecessors. They want to tell an interesting and touching story in a simple garb, fresh with country scenes and feelings.

Zbavitel also discusses the manner of preservation of the folk ballads—preserved, in most cases, in torsos. Referring to two versions of the same ballad, Maishal Bandhu, he argues, "The 'original' ballads [were] sometimes rewritten by another folk poet, or other poets, quite freely, without any scruples; whole portions, as well as individual couplets and verses, were taken over, others were replaced by newly replaced passages, and the story itself was often changed." The reasons behind such changes, according to Zbavitel, might be an effort to offer listeners a 'better' story than the original one.

Due to this oral nature of preservation, it is always difficult to prove the originality of folk elements. If we undertake an effort to study the folklore of Bangladesh, Zbavitel's book will be an invaluable companion guide.

Rabindranath Tagore wrote to Dinesh Chandra Sen in appreciation of the book Maimansimha-gitika, "Classical Bengali literary texts such as Mangal-kavyas are ponds dug on by order and at the expense of the rich, but Maimansimha-gitika is a source of exuberance from the deepest level of the heart of rural Bengal, a clear stream of genuine pain. There has never been such a creation of self-forgetting rasa [aesthetic joy] in Bengali literature." [translation by the author]

While celebrating the Bengali new year this Pohela Boishakh, may we remember the melody and the essence of communal harmony embedded in Maimansimha-gitika.

Shamsuddoza Sajen is a journalist and researcher. He can be contacted at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments