In "Taxi Wallah", Numair Atif Chowdhury takes us, once more, through the cartography of a homeland

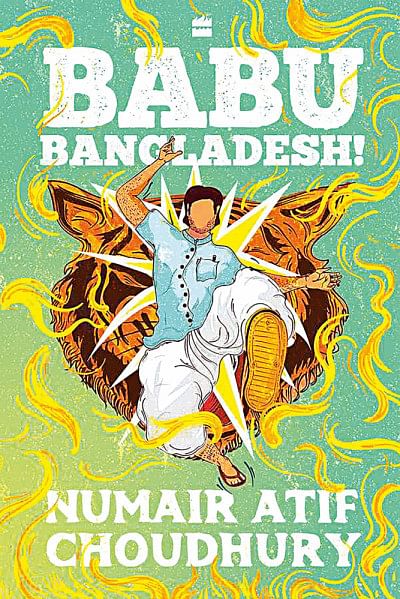

The version of Bangladesh we received in Babu Bangladesh (2019) was astonishing. Not because we didn't recognise the violence, the resilience and the political cross wiring making up the story of this country recounted in the novel, but because watching these seemingly banal details of our existence elevated to the ranks of magic realism had not been offered through literature in a long time. Not in the presence of a global audience, at least. As mind bending as Numair Atif Chowdhury's way with language was, winding and soaring and crawling through the page to bring to life a nation miraged onto a man, the more precious treat was to realise that the images, the textures, and the anecdotes of our own childhoods can rival those of Gabriel Garcia Marquez's Colombia or Roberto Bolaño's Chile as ingredients in the process of myth-making.

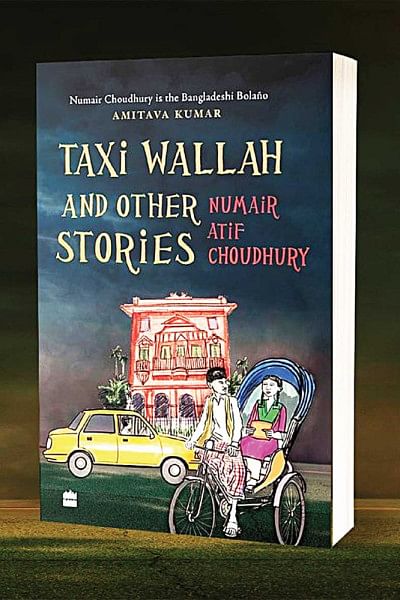

The novel, Chowdhury's portrait of his country, felt like tasting alchemy, and from that bubbling cauldron the author offers us a small dose of its capital city in his Short story, "Taxi Wallah". It spearheads Taxi Wallah and Other Stories (2021), HarperCollins' recently released collection of older, critically acclaimed short fiction by Numair Atif Chowdhury, including "Rabia", "Chokra", and others.

In "Taxi Wallah", as in his novel, Chowdhury is interested in the anthropological filtered through the lens of the spatial—in how spaces and lives draw energy from each other and how their exchange shapes demarcations in class, in experiences and temperaments. But while Babu Bangladesh so cleverly wrought a mirage of Bangladesh, using fragment upon fragment tied loosely together by a distanced and overeager narrator, "Taxi Wallah" takes a more direct approach. We hop into a taxi at the front gates of Dhaka's international airport and we sit in the backseat of its driver's mind as he takes a just-arrived foreigner across the city to Purbani Hotel.

Dhaka as we know it, and as some of us—foreigners especially—would never know it, comes alive. Shadows and voices of other spectators muffling the pirated films shown in theatres. Not men and women but "expressionless skin and bone" sitting outside the Masjid. Bostis with bloated bellies, drunken labourers, abused third and fourth wives. In Gulshan the air stiffens with traffic and new wealth. In Banani it throws a newly arrived villager into panic. Mohakhali, where our taxi driver lives, carries the stench of fryers from mishti stalls, cassette tape music wafting in the air. Balloon wallahs, paan wallahs, amra wallahs all go unnoticed by his passenger who has flown in this time to "spare" Dhaka some time.

There is nothing new in discovering a city through its less glamorous underbelly. What Numair Atif Chowdhury does here, in the way that only he can, is map the cross currents and undercurrents buzzing through the city onto a compact, visual whole that we can absorb an inch at a time and all at once. It is Dhaka collaged onto a mood board.

He evokes, also, the texture and flavour of moving through life in the city, which feels so often like sludging through a lake bogged and sprinkled with the detritus of overcrowded, discriminate inequality. As our taxi wallah's mother says of his eyes, life in Dhaka can often be like "dirty water: hiding the insides, not letting light through".

What redeems it?

The same precociousness that supported the heft of a novel like Babu Bangladesh, that inspired its author to work on a single novel for 15 long years. The precociousness of a street child who shoots a rajanigandha against the glass panes of the speeding taxi, in rage, afraid but fragrant with resilience. "Like anyone who has held a newborn and let its weight sink into their arms," the taxi wallah reminds us, "[we] know there must be a way out of what we are doing".

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor of Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected] and @wordsinteal on Twitter and Instagram.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments