The alter ego of Agatha Christie

Earlier this year, perhaps sometime in April, I had the brilliant opportunity of reading Absent in the Spring (Collins, 1944) by Mary Westmacott. It was a beautiful novel about an elderly woman who is returning home to England after an extensive visit to her ailing daughter in Iraq. Now stranded on an isolated island in Baghdad, amidst a terrible flood and with no recreation to keep her busy mind company, Joan Scudamore finds herself in a sea of her meddling thoughts.

She is not a person who has had much time to invest in herself. Family, friends and children were always the foremost in her long run of life. It was a case of self-induced ignorance for her, Joan felt mighty better without dealing with the complexities of human nature. I was in awe while reading this novel. To see Joan facing her fears, chased by the wicked lengths of reminiscences and questioning everything she held dear was at once fatal and eye-opening.

Mary Westmacott was an author I had known and loved for years. Her novel And Then There Were None (Collins Crime Club, 1939) was one of my first dives into the mystery genre. Although my experience with her timeless classic was unfortunate, her elegant writing pattern and genius storyline ensured I made a return visit. To this day, her Miss Marple series remains an intimate friend, with whom I hang out rather often. So you learn my surprise when I encountered a beloved author, deeply familiar to my heart, penning something (an entire novel at that) that goes beyond the normative structure of her success. Someone I had come to admire as 'The Queen of Crime' was also a master in other forms of literature, and I only discovered it now!

The reason why I keep addressing her as Mary Westmacott, when her birth name is decidedly more popular, is because I find it interesting how often readers tend to forget about her versatile identities. Mary, or should I say Agatha Christie—the great originator of one of the most marvellous criminal detectives of all time, Hercule Poirot—is an author of varied qualities. To think of her as a crime novelist is a disservice to her talent, and in the wake of her 133rd birthday, I am here to present you with her Westmacott merits.

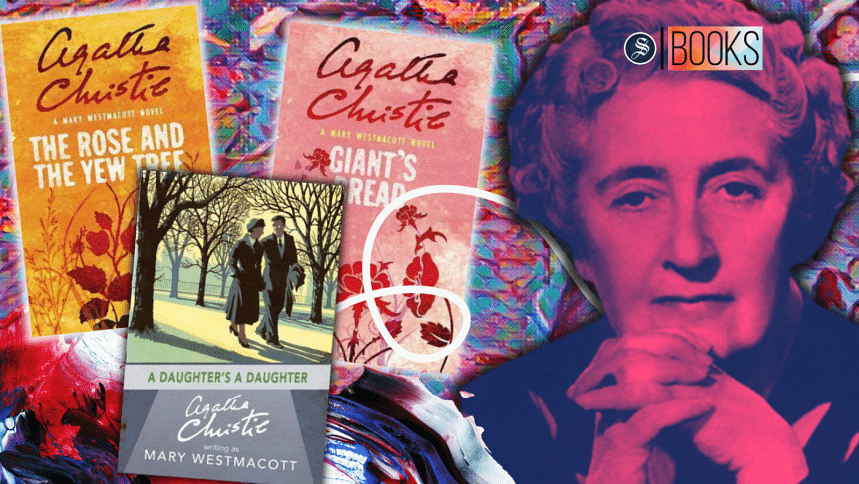

In her lifetime, Agatha Christie produced 6 novels under this pseudonym, starting with Giant's Bread in the year 1930. It was not until she was very well established in her career as the 'Queen of Crime' that she had decided to experiment with her prose a little more. For almost 20 years, Christie was successful in concealing her identity as Westmacott, ousting herself after the fourth book The Rose and The Yew Tree in 1948.

Most of her literary works, read and critiqued by the scholars, were deemed as semi-autobiographical. Christie wrote out her life on the blank canvas of literature for hundreds of people to see. In a way, it was her method of catharsis; a bolt for freedom from the stuffy premises of reality. This notion of her books being journal-like was confirmed later on in Christie's real biography, Agatha Christie: An Autobiography in 1977.

Three of her books: Giant's Bread (1930), Unfinished Portrait (1934), and A Daughter's a Daughter (1952) bear the closest resemblance to her personal life. In Unfinished Portrait, the author pans a lifelike portrayal of her circumstances with her first husband, Archie. The sense of diffidence she underwent in the company of misery when Archie decided that he was not in love with her anymore. At the heart of Giant's Bread, we follow Nell and Vernon, both of whom carry Christie's individual flair. Nell's time as a wartime nurse and Vernon's struggle to choose between the two women who love him.

However, the delicate most depiction of her life was explored amidst the plotline of A Daughter's a Daughter, where Christie presented the audience with a raw, heart-wrenching recount of her relationship with her own daughter, Rosalind. Through the characters of a widowed mother, Ann and her coming-of-age daughter, Sarah, we understand the internal dynamics of a mother-daughter alliance.

All of her Westmacott novels are based on an authentic setting of the post-World War, against a developing England in the early to mid 1900s. Much similar to her authentic backdrops, the premises of her novels are also original. While her whodunits are focused around the mysteries of murders, her literary fiction novels are more concerned about the mysteries that conjure up human nature. These novels are about the bitterness of life, the sweetness of living, and the wistfulness of love.

That is not to say you would not be able to identify her authoring pattern reading these novels. In classic Christie fashion, these books are deftly paced in the run of her popular ingredients—intrigue and twist endings.

Absorbing these books is like viewing the world through the writer's eyes—the pain she felt, the love she did not receive, and the manner she perceived the people around her. Although I am a fanatic for her whodunits, it is always a refreshing experience with her pieces of literary fiction. These genre-bending, expectation-exceeding literary works are as much a part of her virtuoso identity as are her classic, well-favoured mystery novels. Thus, if you are looking for an entirely new exploit of Agatha Christie (precisely: if you want to read Christie but with more clichés and drama), start with any one of her Westmacotts.

Nur-E-Jannat Alif is a Gender Studies major and part-time writer, who dreams of authoring a book someday. Find her at @literatureinsolitude on Instagram or send her your book/movie/television recommendations at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments