The records of resilience

In the midst of a brutal war, 61 young men were taken in for training at Murti in India, where an airstrip had been constructed during the second World War. It was, as Rafiqul Islam, Bir Uttam, says, "Set in the deep jungles and surrounded by tea gardens." Here the men, mostly university students, were brought in. The war needed leadership and these men had been chosen from among thousands for this special course.

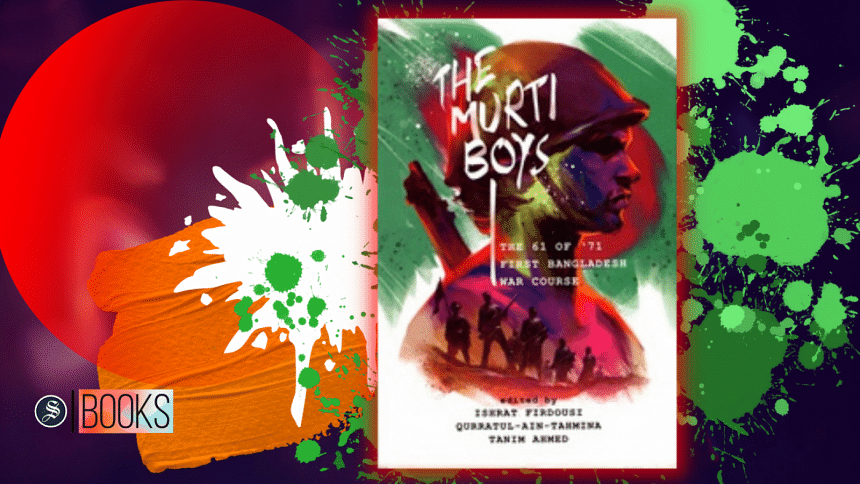

Edited by Ishrat Firdousi, Qurratul-Ain-Tahmina, and Tanim Ahmed, The Murti Boys (University Press Limited, 2022) chronicles this history. It is a story weaved together through the eyes of the soldiers themselves, their trainers and in some cases, their family. The Murti Boys at its core sheds light on a tremendous story of resilience and courage. Through their accounts we are transported back half a century away to witness the carnage. Their surprise at the quick end of the war, their thoughts on the biharis, the Rajakars, and the Indians helping them are one of the many reasons why this book is a captivating read.

These young soldiers were all to become second-lieutenants and head platoons or command guerilla units. Brigadier RP Singh, who was an instructor at Murti, says in the book, "The whole syllabus of tactics, field and battle craft, weapons training, physical training and unarmed combat was compressed into a capsule of sixteen weeks…" That, too, was later shortened, as the situation of the war signaled their early graduation.

The war itself was a reality check for this meritorious bunch. "At the Academy we trained with live fire but it was still safe barring accidents or outright stupidity", says Lieutenant Colonel Mahbub-Ul-Alam, Bir Protik, "Nobody is shooting at you with the intent to destroy you. And training can be fun. This was something else."

Much of the reminiscences in The Murti Boys encompass the grittiness of staving off the Pakistanis with little weaponry and a great deal of quick thinking.

Indeed, what this compilation offers best are glimpses of wit, bravery and the sense of loss of these soldiers. Flicking through the pages, one cannot but be amused when Shahzaman Mozumder, Bir Protik, recollects: "I was told that researchers had unearthed a letter from an exiled Bangladeshi politician to the Indian authorities in which his required list of weapons and ammunition was rounded off with the cautious request for a few 'chhoto-chhoto atom boma' (tiny atom bombs)!"

There are instances of great restraint. When Major Didar Atwar Husain comes in possession of a couple of Pakistani soldiers, he tells them not to be frightened. "We are not as bad as you are," he says, "We follow the Geneva Convention."

The academic Kaiser Haq's essay was among the better written portions of the book, and his accounts of buying books such as Dr Zhivago and Age of the Guerrilla to take to camp and being part of the "Hamzapur Tigers" were an engrossing read.

Even here, the role that women played during the role can be glimpsed at, if only briefly. Major General Syeed Ahmed, Bir Protik, says in a chapter: "Saira, the 20-year-old daughter of a Razakar…was a brave young woman who got information about the Pakistanis from her father and relayed it to the freedom fighters, information so rich in detail that I knew exactly what the Pakistanis had and where."

However, going through these narratives can often be unpleasant. The book is poorly edited, surprisingly so for being shaped by veteran journalists. Typos abound as do puzzling repetition of entire chunks of paragraphs. The reader cannot be faulted for being put off by the project's lack of coherence. As some parts have been written by the freedom fighters themselves and some were translated or transcribed from interviews, there is a noticeable discrepancy in the prose style. The odd mix has resulted in a peculiar reading experience which is rescued by the sheer intrigue and appeal that only war stories can provide.

For that reason alone, The Murti Boys is worth a read. It documents a piece of our history that demands an audience.

Shahriar Shaams has written for Dhaka Tribune, The Business Standard and The Daily Star. He is nonfiction editor at Clinch, a martial-arts themed literary journal. Find him on twitter @shahriarshaams.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments