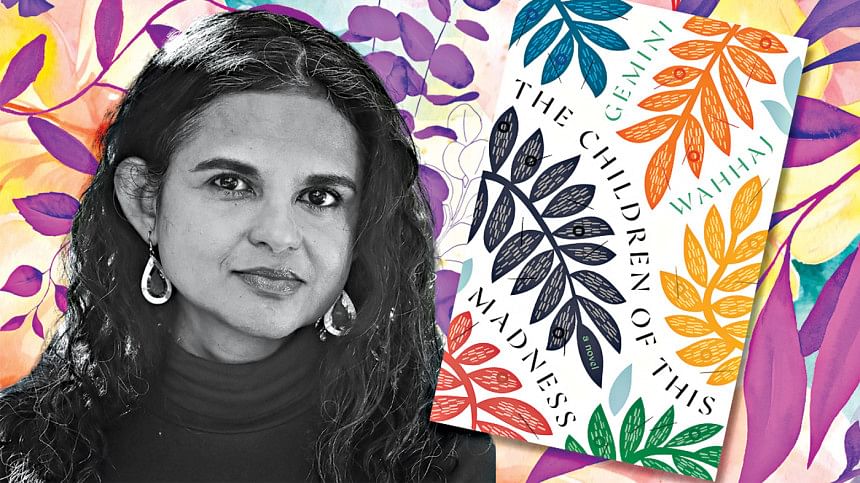

The stories we want to tell: In conversation with Gemini Wahhaj

In Gemini Wahhaj's debut novel, The Children of This Madness, the narrative revolves around the lives of engineering professor Nasir Uddin and his daughter Beena, an aspiring PhD candidate living in the US. Nasir Uddin rises from humble beginnings to become an engineering professor amidst the backdrop of the '47 Partition & '71 liberation war, while Beena chooses to pursue literature and begins her PhD journey in the US. This isn't your conventional immigrant story. Told through the altering voices of a father and daughter, it's a book about aspirations, the weight of the past, and the journeys we take.

Shedding light on the intricacies of the Bengali-American immigrant journey, this book serves as a significant contribution to our evolving diasporic literary landscape. Wahhaj, with an engineering background, penned the novel while pursuing her graduate studies in the creative writing program at the University of Houston.

During our conversation, Wahhaj shares about the narrative style of her book, the emergence of her protagonist's voice, inspiration that led her to write about the children of madness, her experience with publishing with small presses, and more.

To begin, the narrative style for this book is quite intriguing. You crafted the narrative of the book through the dual lenses of a daughter and a father, and there is also Rahela, the mother, whose perspective comes into focus briefly. While portraying Beena, you opted for a third-person perspective, but for Nasir's character, you chose a first-person narrative. Could you elaborate on the reasoning behind this stylistic choice?

I've been receiving this question quite frequently, and it's intriguing to observe the various perspectives people have. When I initially wrote the book, it took on a different form organically. There were numerous chapters, yet none focused on Beena. So, the book was organically a completely different book, and there were many more chapters about Rahela. And, the alternating first person and third person voice wasn't a regular pattern either. Sometimes, I portrayed Nasir Uddin in the third person, while other times, I adopted a first-person perspective. My aim was simply to narrate the story in whatever manner seemed fitting. It was linear; I was progressing towards an end in an arc. In each chapter, I was trying to tell a certain part of the story from the best possible angle. So, I wrote the novel in a very different style, and then I realized that in America there is an expectation that a novel has to be structured in a regular style pattern of a dual narrative, and be structured. I was told that the book is good, but I couldn't have five chapters from one character, then suddenly one chapter, and then ten. The reader has an expectation. So, I completely changed the structure of the book. The honest answer is I was responding to the structural expectation as it's my first novel.

It's intriguing to learn that there were initially no chapters dedicated to Beena, especially considering that she and her father, Nasir Uddin, emerge as the primary characters in the final manuscript. Can you elaborate on when Beena's voice started to take shape within your story and ultimately became the central focus?

In the original manuscript, Beena had no story. She is simply an unsuccessful daughter lamenting, "How did this happen? My brother isn't successful, I'm not successful, and my parents are a mess," while everyone else thrives. For me, that impulse and question is authentic. Because I'm not successful. My parents died young. My husband and I aren't successful in the traditional sense. It's a quintessentially Bengali question to pursue success, no matter how idealistic you are. You aspire to win. I believe that's a significant aspect of the middle-class Bengali identity, even though we may not perceive it that way. I had to live in America for 20 years to find out Beena's story. Her narrative revolves around securing her immigration status because when you arrive in America, your primary focus becomes security. You view yourself in terms of your immigration status and employment. When I see young people who have just arrived in America and see how much they have to get in place, I'm both surprised and reminded of when I first arrived. They are preoccupied with their job, their OPT, and the expiration of their F-1 visa. They inhabit an entirely different realm. That was Beena's story, that she was desperate to secure her position. When Beena was not part of the story, when she was simply a bookend, I could portray her as a flawless, innocent character who observes the other Bangladeshi immigrants and asks, "Why are they so corrupt?" But when she became part of the story, she had to become more like the other characters. That's why I had to write her in the third person, as she gradually mirrors the people she questions. It was challenging to write her as an innocent character because ultimately, she chooses to pursue citizenship and assimilate into that lifestyle.

You start your novel with an epigraph from a poem by Saadi Youssef, and the novel's title is also derived from that. Talking about the characters, the protagonist Beena witnesses the invasion of Iraq, and also her life is kind of uprooted when her mother and brother are killed in a blast in Dhaka. There's also Nasir whose life is completely different than that of Beena's. He has had a rough childhood and survived the '71 war. They are born out of madness in their different ways. The central theme of the book is about the lives of people caught between a war and its aftershocks. What drew you to write about these children of this madness?

When I used the title "Children of Madness," I thought they were literally the children of the mad guy! But you are right about the poem. The poem is about Iraqis, and I think the lines are saying that so much history of war and suffering has come before us; we are the children of this madness—but it is up to us what choices we make about how we live. For me, one compulsion for the novel was the Iraq war in 2003. When I was writing the novel, it was right after the Iraq war had started in 2003. Throughout my teenage and adult years in the US, Iraq was a constant presence—Bush Senior's war in 1991, the weapon inspections in the 90s, bombings of Baghdad during Bill Clinton's presidency, and then the invasion of 2003. I was witnessing the buildup of this political tension throughout my entire conscious life. There was always a sense that it wouldn't happen, until it did in 2003.So, it was really the shock of the Iraq war. Also, in America, there aren't many novels about the Iraq war. There are numerous narratives about it, but they're mostly from the American perspective—focused on veterans who served there, the devastation experienced by their families, and the PTSD they endure. It's all seen through an American lens. Yet, there's a notable absence of narratives from the Iraqi perspective. I'm not Iraqi, so I couldn't write that novel either. But I wanted to write about how it feels to just helplessly watch the Iraq war unfold. And the other impulse was to write about the Bangladeshis who are settled in America. Who do you become when you decide to settle in America? I'm not criticizing that, but the Bangladeshi characters in America are primarily focused on their own concerns—like getting a house, citizenship, and a job. They become almost divorced from society, uninterested in American culture or the people around them, and indifferent to conflicts like the Iraq war. Your whole identity shifts. I don't feel like the same person I was when I first arrived here. Bangladesh has receded in my memory. I'm now much more engrossed in the politics and issues here. But the Bangladeshi immigrants I've encountered in Houston seem very divorced from society. They were not concerned that there was a war going on in Iraq. The Bangladeshis I know are deeply entrenched in capitalism and tied to the corporations that employ them. They hold a narrow view of success, which revolves around earning a lot of money and possessing power. When I first arrived here, I wanted to be a part of the Bangladeshi community. However, I soon realized that we have completely different values. When I first came here, I was still deeply rooted in my Bangladeshi identity. But I've changed so much, just by becoming an American, by deciding to become an American citizen. I was interested in exploring what that is—not to pass judgment, but to explore what identity is, and how it intersects with citizenship.

It's interesting that in the end Nasir Uddin has his homecoming when he returns to Dari Binni, and finally feels at ease. He has his resolution. But Beena has this sense of frustration and anger, especially towards her father. She also experiences a sense of not fitting in anywhere. Is Beena ever able to find her sense of homecoming or closure?

I was surprised when multiple readers asked me, literary agents, "Where is the redemption?" Now I believe redemption means a happy ending as an American, a happy immigrant story. A classic immigrant novel would be that you come to America, and you are just so happy to be here. I don't know if Beena is happy. I don't think she's unhappy either. I have a great fondness for Roberto. So, I believe she found a good partner, made a wise decision, and will be okay. But that's the decision she made. It's hard to explain, but I feel she's stuck. If I wrote a hundred immigrant stories, they would all be stuck. They would all share this common sentiment of being stuck.

How do you personally navigate your identity as a Bangladeshi American writer, including the expectations and perceptions associated with it?

That's a really good question because I have grappled with that [expectation] for 20 years. I'm not sure if you're aware of how this novel was published, but it didn't come from a mainstream or big-five publishing house. For 20 years, I worked on numerous manuscripts and sent them out, often coming close to securing an agent. But I was told: you should change this, and that's the story we want. Eventually, I chose to work with a small press. I think that small presses are more open to narratives beyond commercial tropes and willing to take risks. However, the moment I consider returning to the mainstream game of finding an agent, those expectations resurface immediately. When I had two manuscripts accepted, I was discussing a third manuscript with two agents, it seemed like they were annoyed when my second book was picked up. One of them, in particular, told me, "I don't understand the commercial value," despite the fact that another publisher had already signed it. I found the comment disheartening. I kept writing blurbs explaining, but the agent continued to question why people would be interested. I want to write to pursue my own ideas and my own projects. Agents often stress that to be a career writer, you can't write solely for yourself—you have to write for an audience. My question is, who exactly is the audience? The imagined audience that big publishing houses envision is a constructed, artificial one. Therefore, I don't believe it's true that there aren't readers for the kind of risky stories we want to write. I want to leave all of those questions of commercial value behind me because I'm getting older. I've waited 20 years to publish my debut novel, and I have so little time left to produce the kind of writing I want to create. I simply want to focus on doing my best to practice my craft.

Can you share a bit more about the publication process? What was it like for you, from initial submission to seeing your work in print?

I didn't have an agent. To get published with a small press, you have to send your manuscript. Most small presses have submissions open at certain times of the year. Sometimes there are contests for you to send your manuscript. So, I did that. That's how I was published. It takes about a year from there. It's accepted, and then they send you editorial feedback. Then, there are rounds and rounds of detailed editing, fact-checking, and proofreading. It was exciting to see it progress closer to becoming a book, but then I would have to read it again. And as you get closer, you have to make sure it's good. I had my publisher and editor read the manuscript. So, there were multiple sets of eyes on it which made me feel secure. When I was editing the book, my entire focus was on the manuscript. I had little capacity for anything else. I couldn't move in the world. I had an accident one time backing out of a parking lot! I just wasn't interested in daily activities. All I could think about was getting back to my manuscript.

You have waited 20 years to publish your debut novel. It wasn't an easy journey. At this point in time, how do you feel now that your book is out in the world?

It's an incredible feeling to hear from readers—knowing that many people are reading my book and engaging with it. That's exactly what you hope for as a writer. Even if only one person or five people read your book, you still feel it's worthwhile, and it motivates you to keep writing. I don't believe anyone can write in a vacuum. Although I have done so for many years, I think I would have written much more if I had been published. So, it feels incredibly validating to be published and to have the opportunity to work with an editor. Having someone appreciate your work and help refine it is truly important; it's not just a matter of typing it up and sending it off to a printer. This experience feels good, and liberating. It gives me permission to write more. Now, I can write without worrying, "Oh, what will happen? I'll simply write, and it'll be saved in my drive. Why write?" Those questions no longer plague me. Now, the question is: "Am I good enough?" I want to make sure I write something good that I am proud of.

What's the next thing on your plate?

When you say "next," it's kind of hard! I have a short story collection that will be released in January. Right now, I'm working on revising and completing a manuscript—a novel based in Sylhet. I also have another manuscript in mind that I'm eager to write—it's my immigrant story. I'm particularly interested in exploring the experiences of immigrant women living in America who are also mothers and delving into their feelings of being lost and confused. Initially, I attempted to write it as a memoir, but it felt too personal and traumatic, so I decided to approach it as fiction. And I'm getting together new stories for another short-story manuscript.

Usraat Fahmidah is a freelance journalist & writer. You can find them on X @usraatfahmidah.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments