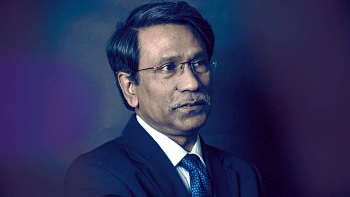

Rifat Munim on Bangladeshi fiction: ‘This is a diverse terrain you are going to tread on’

Syed Shamsul Haq, in his short story "A Life Like A Story", talks about how the contours of a conversation confuse. They split into pathways, twist, bend, and often circle back to the place where they started out. Haq's narrator finds this exercise futile. "And so our differences on issues never get resolved; arguments keep piling up", the text reads in Khademul Islam's translation. "Our feet keep on walking, but our destination—we don't speak about it."

But this narrator is tricky. He too begins a conversation with the reader. He walks us through multiple realms—across the page, step by step from Hanif Bhai's sweatshop to Kashem Chacha's tea stall by Jaleshwari's riverside, into and out of Kashem Chacha's family history—and he brings us back to the place where the story started out. But the little things that shifted and flipped during this walk upend the way we see each of these characters. It disproves the narrator's earlier point: we realise he had wanted to complicate our understanding of a conversation all along. Haq's story demonstrates one of the underlying points of fiction—it is the story itself, the movement itself, the differences themselves that build the blocks for resolution; resolution is never neutral, nor neat.

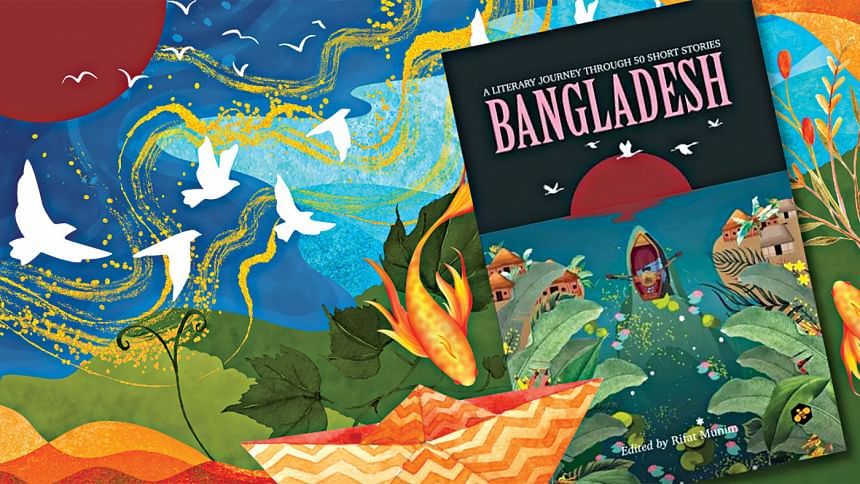

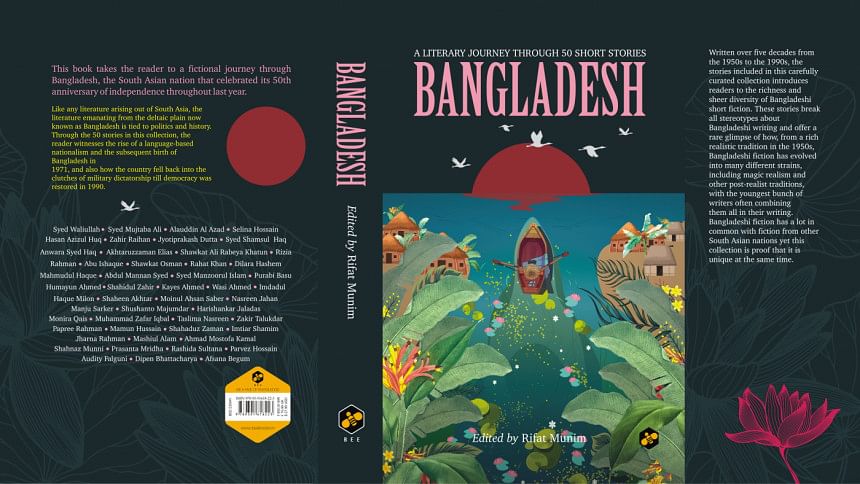

When Rifat Bhai and I sit down to talk about Bangladeshi fiction one evening, last year, in the golden glow of the Daily Star Books cubicle, we too veer messily, into and out of topics and time periods. We're there to discuss Bangladesh: A Literary Journey Through 50 Short Stories (Bee Books, 2023), the first short story anthology Rifat Munim has compiled after a lifetime spent reading and eventually translating literature, having worked for over six years as a literary editor at The Daily Star and Dhaka Tribune. I have close to eight questions that I want to ask him about his relationship with Bangladesh's literary scene; he answers twos and threes of them in one go, without even knowing I would've asked him to address each of these points. Our conversation shoots off and stutters in random directions, from the literary heyday of the 90s to how customs charges make it difficult to bring one's own books into the country. We discuss the unwieldy, exciting process of putting a book together.

Bangladesh, like its namesake and much like my conversation with its editor, spills in many directions. Syed Shamsul Haq's "A Life Like A Story", steeped in political realism, rests in the collection alongside Anwara Syed Huq's magic realistic "Hands", translated to the English by Shabnam Nadiya. There are stories by Syed Waliullah, Shaheen Akhtar, Syed Mujtaba Ali, Selina Hossain, Akhteruzzaman Elias. Translations by Naeem Mohaiemen, Shahroza Nahrin, Fakrul Alam, Arunava Sinha, Noora Shamsi Bahar. It is a heavy book—I struggled to carry it when I first received my copy—and the scope of its stories, the literary strains it covers, and the writers and translators it puts in dialogue with each other would spill messily out of any reader's hands. "With this book I wanted to show how diverse Bangladeshi literature is", Rifat Bhai reiterates through our hour-and-half-long chat. These are the anthologies that, as a reader, I find most exciting—the books unconcerned with "organising" a literary landscape into a neat picture, books that are more interested in difference, contradiction, movement.

What struck me about this collection, in comparison to the other anthologies we have had in Bangladesh recently, is that it gives us a deep account of how your own journey with stories evolved. It seems like this book came out of a very personal space. Can you tell us about that?

In the foreword, I wanted to capture how I, as a child, grew up listening to different stories: ghost stories, mythical stories from both Sanatana and Islamic religious scriptures, and fairy tales from Thakurmar Jhuli, compiled by Dakkhinaranjan Mitra Majumdar. It was a time when there were no boundaries for my imagination.

When I moved on to high school and then to college, I was heavily influenced by leftist writings translated into Bangla—not only all those books of critical theory by Marx, Engels, Lenin and Mao Zedong but also the fictional writing by Maxim Gorky, Nikolai Ostrovosky and Lu Xun. In the Marxist circles in the 1980s and 1990s, there was this discourse that we should focus more on realism than imagination. But because of my exposure to these different sources of stories in my childhood, I always had a penchant for limitless imagination. It taught me that literature shouldn't be defined in restrictive terms.

I write about this at some length in my foreword because I believe that the realm of Bengali literature is heavily defined by several discourses. Proponents of one discourse are at loggerheads with those of another. But there are writers who push the boundaries. I came to realise that creative fiction has the power to defy the restrictive theorisations of literature.

As I delved more and more into the realm of Bangladeshi short fiction and novels, I have found out Bangladeshi fiction has grown to be very powerful and diverse. Due to poor focus on translation, our fiction and poetry have stayed within the borders of Bangladesh. It's only recently that this has started to change thanks to translators like Kaiser Haq, Mahmud Rahman, Arunava Sinha, Shabnam Nadiya, and V Ramaswamy.

My urge has always been to promote Bangladeshi fiction through translation. So when the hype for Bangladesh's 50th independence anniversary came around, Arunava Sinha reminded me that perhaps it was about time I edited an anthology of translated short fiction from Bangladesh. I couldn't agree more with him that the time was right.

One of your other main goals was to challenge stereotypes cast around Bangladeshi literature. Which stories from the collection do this?

I think I tried to challenge such stereotypes through my selection of themes, storytelling techniques, writers, and also translators. The first stereotype about Bangladeshi literature that I encountered was: realism has too big a hold on our biggest writers including Hasan Azizul Haq, Elias, Selina Hossain and Rizia Rahman. This is a baseless claim. The second one is about the dearth of international-standard writing from Bangladesh, which is another baseless claim feeding on our colonial mentality. Who is the authority to decide what retains international quality and what doesn't? The west usually sets different priorities in different eras. If non-western writing fits in with those priorities, it is occasionally published in the west and gets an opportunity to be celebrated. That's why the ratio of translation of non-western books into English is so poor compared to western books. We should come out of this colonial mentality and focus instead on quality translation of our books not only into English but also into other South Asian and Asian languages.

One of the interesting aspects about stereotypes is that they share a lot of underlying beliefs constructed around binary oppositions, such as serious writing and popular writing, men's writing and women's writing, male translators and female translators, native translators and non-native/local translators. With my selection, I have tried to challenge the notions implied through these stereotypes and binary oppositions. Among other things, I have tried to show men can write about women's issues with aplomb and women can write about all the issues under the sun, including their own, that Bangladeshi female translators are doing a better job than their male counterparts, that writers from as early as the 1960s and '70s defied the dominant literary norms of their times and told their tales in innovative ways.

An anthology can be an equalising force as much as it can select and exclude. A glimpse at this book shows a dialogue forming within and beyond literary timelines: in the table of contents, we have commercially popular writers like Humayun Ahmed listed alongside academically revered writers like Syed Manzoorul Islam. We have literary giants such as Akhtaruzzaman Elias listed alongside emerging translators. How do you edit an anthology? And what do you think the form can accomplish?

Back in 2021, I attended a four-day virtual workshop focused on the challenges of literary translation and editing translation. It was organised by the Commonwealth Foundation. On the second day, acclaimed writer and Chinese to English translator Jeremy Tiang—who was the 2022 International Booker Prize jury member and who has written powerful essays about decolonising translation—stressed that the best way to promote the writing of a particular language or country on to the world stage is through anthologies because an anthology presents to publishers, critics and editors of the target language a diverse array of writers who each have their different ways of storytelling. I totally agree with Jeremy.

But different editors make different choices. The most important aspect of an anthology is to decide on the angles or themes around which an editor wants to organise their book. An anthology may focus on a particular theme, such as the partition of India, the liberation war of Bangladesh, feminism, modernism, etc., or it may aim to feature powerful writers from different eras. In my case, in addition to my personal attachment to Bengali fiction, my working experience as a literary editor shaped my choices. As a literary editor, and also while working closely with the directors of Dhaka Lit Fest, I felt there was, and still is, a serious lack of an anthology that makes a comprehensive attempt to introduce foreign readers to the richness of Bangla fiction emanating from Bangladesh. Yes, there are many anthologies but they either exclude many important writers of our Bangla fiction on arbitrary grounds or they combine original English writing with translation of Bengali writing.

Therefore, I wanted to present an anthology focussed solely on the translation of Bengali fiction that would be inclusive both in terms of containing the representative authors from the 1950s to the 1990s and showcasing the rich diversity of our fiction. Above all, I wanted to give the target audience a sense of how the modernist, Marxist and feminist impulses of Bangla fiction from this part of Bengal have evolved into newer strains that not only challenge European modes of storytelling but also combine Western and non-western traditions of storytelling. I also tried to make sure that all the seasoned and emerging translators of our fiction are represented in this anthology.

But no matter how hard you try and how thoroughly you research, there comes that inevitable moment when you have to include some at the expense of some others. That's the tricky part of editing an anthology like this one. A couple of writers have alleged that they have been excluded even though they belong to the 1990s generation. Their allegation is true but this is not a 3,000-page academic anthology. It has to exclude some and it does not mean the excluded writers are not great writers.

The unifying principle for this anthology is the thematic and stylistic diversity and development of our Bangla fiction. That's precisely why popular writers like Humayun Ahmed and Imdadul Haq Milon are selected alongside Hasan Azizul Haque, Akhtaruzzaman Elias, Selina Hossain, Rizia Rahman, Qayes Ahmed, Manju Sarkar, Wasi Ahmed and Shaheen Akhtar, among others. Some readers/writers have expressed disapproval about including popular writers in this book. The popular elements in Humayun and Milon's work do not disprove the fact that they both have written very powerful stories and novels and plays. While editing an anthology of classic authors of Bengali fiction, if an editor includes Tarashankar, Manik and Bibhutibhushon but excludes Sharatchandra because he was a popular writer, then I'll say this is a poor editorial choice.

I am a politically oriented literary critic with some solid fondness for innovative and authentic storytelling techniques. But my own predilections should have no bearing on the choices I make as an editor. As an editor, my job is to make sure that every significant aspect or strain of our literature is represented.

What is your take on the state of literary criticism in Bangladesh today?

The state of literary criticism needs to catch up to the pace at which our creative writing is progressing. The only good critical writing is being done in academic circles, but in Bangladesh, academic writing does not get a wider audience.

Good literary critics are emerging; a lot of seasoned literary critics are already there. But I don't think they are making as big an impact as those right before and after Bangladesh's independence did. For a critical culture to flourish, first we need an atmosphere where one can freely write about their views on a book or a writer, views that are supported by strong arguments. Secondly, we need literary publications where such writings can be published. Currently, we have neither the atmosphere nor those publications. Commercially successful newspapers, which even a decade ago gave a lot of space to literary essays and book reviews, are cutting their literary supplements down to a page or two that only publish short pieces of fiction and feature, and favourable reviews, if at all.

I believe only private initiatives can save us from the declining critical culture. By "private initiatives" I mean benevolent people who will donate generously to create funds meant only for literary publications that aim to promote a critical culture, prioritising quality and free expression, and remaining unbiased towards any particular coterie or ideological inclination.

Sarah Anjum Bari is a writer and editor teaching Rhetoric and pursuing an MFA in the Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa, USA. Reach her at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments