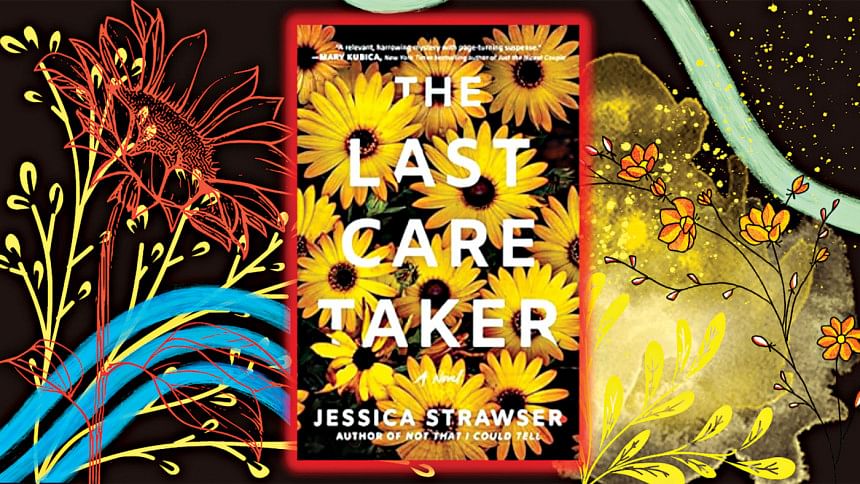

The unanticipated consequences of caretaking

To make significant changes as part of a new beginning after a divorce is a fairly standard response to such a major life change, especially one that is so often traumatic to one or both parties involved. Divorce, after all, is said by psychologists to be one of the top three most intense experiences of grief that a person is likely to experience over the course of their lifetime.

Rather less common as a response is the decision to move out into the wilderness by accepting a job as a caretaker in a nature preserve. But after the humiliating break up of her marriage, that is precisely what Katie—with the support of her best friend Bess, who moved to the area previously with her husband and children to work—decides to do.

But when a panicked woman shows up on her doorstep late at night, expecting a very different kind of help from the caretaker, Katie has to wonder what she has let herself in for, and how much Bess might have known about this hitherto unmentioned part of the job description, since she was the one who encouraged Katie to take the job after the previous caretaker suddenly resigned (and became unreachable).

This is a brilliantly atmospheric story which brings alive the pleasures of the outdoors. From the sensory delights of birdsong in the morning and sunset views from a lookout point to the less appealing realities of monitoring stagnant pond water and counting newts, we accompany Katie on her journey of discovery.

On a very different note, this novel also reminded me of one of the other books I have really loved in recent years—Jessica Barry's Don't Turn Around (Harper, 2020). The similarities are not absolute, but something about the two stories remind me of each other. Not just a few common themes—like the many forms of ugliness that gender-based violence can take, how desperately some women need an escape or an intervention, and the widespread prevalence of misogyny worldwide that we are almost resigned to—but also the sense of fear that the storytelling evokes at times.

There is the unwelcome realisation that most women have encountered this threat in some form at some point in their lives. Whether it is as an observer of the fault lines in the relationships of other couples, or an awkward encounter at a party that could have gone badly, or even just a moment of someone realising their vulnerability in the midst of an argument where the tension is almost physically palpable.

A friend of mine married someone she fell in love with, only to find him to be very different as a husband than he was as a boyfriend. Forced to choose between her marriage and her parental family, her husband and her friends, she became isolated from almost all the people that she loved. This alienation from loved ones is, of course, a strategy commonly used by abusers. And in my friend's case, her own sense of humiliation and self-blame prevented her from seeking help for years. Nor is this all too familiar story in any way limited to South Asia.

Volunteering for a well-known human rights organisation as a student in London some years ago during a mid-career break, I was shocked to learn that in the UK, emergency services received one call for help in a domestic violence situation every minute, and in the US, they received a call every fifteen seconds! As recently as 2019, the cost of domestic abuse to the health service alone in England and Wales (leaving aside the cost to employers and households in terms of sick leave and lost income) has been estimated at £2.3 billion pounds.

If this is the situation in the Western world where laws and support services do exist to protect the vulnerable, one must ask how much worse it might be in a country like India, where the NFHS 5 found that nearly one-third of married women had experienced some form of spousal abuse—most commonly, physical violence.

Interestingly, this novel does indirectly address why such extreme abuse is still unacceptably commonplace in a country like the US. And one of its real strengths is to use the stories of the women that Katie meets, like "Sky" and "Lindsey", to go beyond the economic figures and the mind-blowing statistics and allow readers to just empathise with the incalculable human cost of suffering in these instances.

As Katie soon learns, the job of the caretaker involves not only some unexpected responsibilities, but also a sharpening of the senses and a growing feeling of mistrust or suspicion towards everyone in her life—from her hard-to-read colleague, Jude, who has an unsettling habit of showing up where he's least expected (or wanted), to some of the dog-walkers and bird-watchers in the park, and ultimately, even her BFF Bess...

And even though I guessed one major element of the storyline (the drawback of being a writer who reads is that you are always thinking of how you would write the story that you're reading!), I was nevertheless completely absorbed by the compelling plotline and the beautiful shading-in of tiny details in Strawser's storytelling.

This is a memorable book, featuring relationship dynamics that are easily recognisable, between friends, colleagues, and siblings. It also asks difficult questions about what we accept as normal, and how far we are willing to go in the service of justice—especially when it may involve personal risk. The Last Caretaker is a well-written and thought-provoking novel that, much like her earlier offering Not That I Could Tell (St. Martin's Press, 2018), marks Strawser out as a writer of note.

Farah Ghuznavi is a writer, translator, and development worker. Her work has been published in 11 countries across Asia, Africa, Europe, and the USA. Writer in Residence with Commonwealth Writers, she published a short story collection titled Fragments of Riversong (Daily Star Books, 2013), and edited the Lifelines anthology (Zubaan Books, 2012). She is currently working on her new short story collection and is on Instagram @farahghuznavi.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments