To trace back a tapestry of trauma: Partition inherited

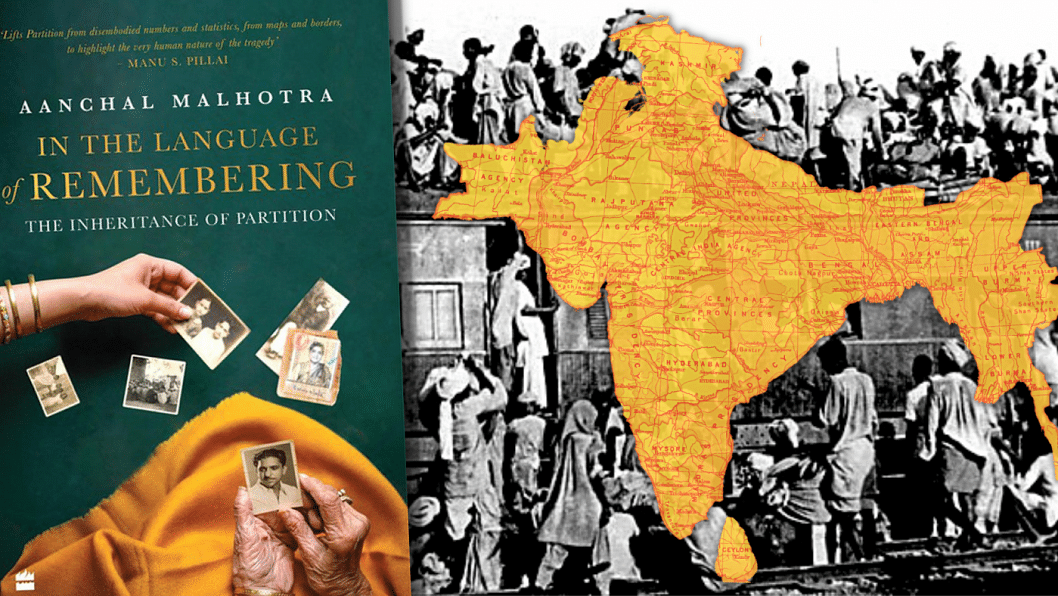

There is a 2018 episode of Doctor Who where the Doctor encounters a group of aliens who, following the decimation of their own species, have dedicated themselves to commemorating the lives and deaths of those who die unseen. Aanchal Malhotra's second book, In the Language of Remembering: The Inheritance of Partition (HarperCollins India, 2022), is an attempt to do just that. Through a number of essays and interviews, Malhotra commemorates lives that were shattered during the Partition of India, and traces those cracks back through the generations to tell their stories. It is an archive of fading memories, of stories untold for generations, teased out by curious and gentle hands.

Those familiar with Malhotra's work, whether through her Museum of Material Memory, or her previous book, Remnants of a Separation (HarperCollins India, 2017), will already be acquainted with her style of interviewing and storytelling. Her project then was to retell the memories of Partition as stored in the physical objects that survivors have kept with them.

The difference, this time, is that the interviewees are mostly generations removed from Partition. To nearly all of them, Partition was something that happened in history books, or a fade-to-black in their forebears' memory that was only recently teased out through multiple conversations over chai. Malhotra acts as witness to these stories, gently giving them guidance; and interspersed between these stories are Malhotra's own thoughts—realisations she has made over years of research and archiving about the nature of memory, of generation trauma and reactions to Partition, and the larger human condition.

Some reviews have complained that In the Language of Remembering does not bring new analysis or insight to the field of oral history and Partition research, but reading through the text, one senses that was not the primary goal of the project. This book's first and foremost goal is to preserve tales that are already fading from collective memories. It is a bonding experience— group therapy, between the interviewees and readers, moderated by Malhotra. The healing and academic analysis of the generational scars comes secondary. The chapters are named as such: Belonging, Identity, Discovery, and so on.

Perhaps better criticism could be levied about the demographics of those interviewed. In Remnants, her research skewed more towards survivors across the India-Pakistan border. This is a problem that has largely been rectified, with many stories now examining the toll of crossing the India-Bangladesh border, not only in 1947, but in 1971 too. The stories aren't all about the two Bengals either—Assam, Tripura, Bihar and other border states get to share too.

However, the tales still all lean towards families that strongly believed in education, are rather well educated, or even wealthy, land owning families. The book never makes a distinction between the love for land owned, and thereby wealth and status, and land lived in, an altogether more abstract, more emotional, and less class-discriminating connection. Why does Pushpa Lata Dewanji, whose family is so influential that Chittagong has a ghaat and a lane named after them, have more of a right to immortalise her connection to land than the farmers who may have tilled the land under her? The class disparity between who gets to tell their stories is one that is often discussed in historical circles, and seeing the lack of representation of more working class folk brings this discussion up once again.

There are a few strange editing choices too. For one, Malhotra sometimes refers to grandparents as "grandmother/grandfather" and sometimes as Nana, Nanu or Dada, Dadu, Dadi. We wish the terminology was kept consistent, especially favouring the latter given how many families and familial branches we follow throughout the book. On that note, given we do not stay with each family for too long, it would help to have an appendix of maps and family trees to help parse the many names and places they come from. Instead, the appendices are dedicated to Malhotra's footnotes, which leave many interesting tidbits hidden in a section of the book many readers may not flip to.

Perhaps the book's best aspect is how it allows space for the stories of those who perpetrated violence during Partition. The story of P, as named in the book to preserve anonymity, may have been the first time I have seen one mention their ancestor in such a terrible light. P spent Partition offering shelter to hapless women who were left by the wayside, only to sell them off later. Such stories are horrific, but very necessary, and if we were to nitpick, we would ask for less punches pulled in the depictions of their atrocities.

That is not to deter one from reading In the Language of Remembering. It never evokes the same emotional rawness of Remnants, but it does patch many of the holes, and brings in new insights compared to its predecessor. The book, along with Remnants, forms a truly beautiful duology archiving the minutia of Partition.

Yaameen Al-Muttaqi works with robots and writes stories of dragons, magic, friendship, and hope. Send him a raven at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments