On weaving family, culture and place into a compelling story

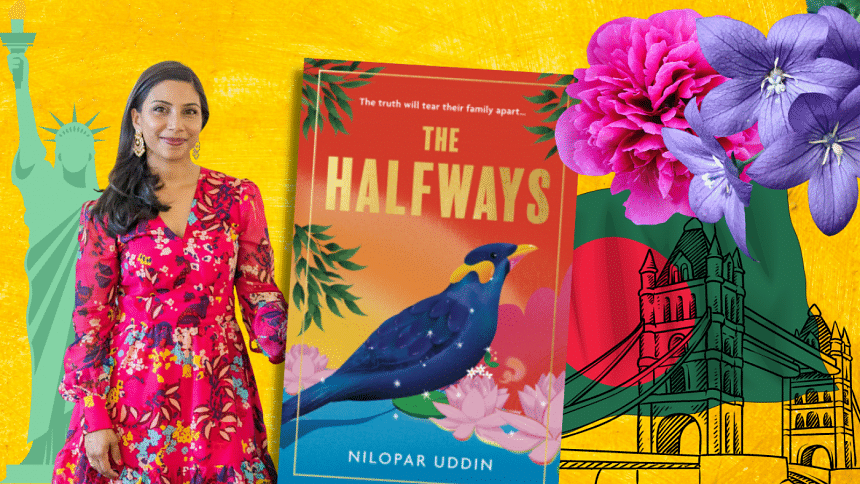

Towards the end of 2022, I came across a book called The Halfways (HQ, 2022) which immediately caught my attention. This novel takes place across multiple cities: London, Wales, New York, and Sylhet, and focuses on the Bangladeshi immigrant experience. At the very core, The Halfways is an expansive tale of a family's journey.

Born in Shropshire to Sylheti parents, Nilopar Uddin's father, like the fictional family in The Halfways, owned and operated an Indian restaurant in Wales. By profession, Nilopar works as a financial services lawyer. But she mentions during our first meeting that she's always loved writing. It was during her MA program that she started working on her debut novel, The Halfways.

The book follows the lives of Nasrin and Sabrina, two sisters who appear to be living successful lives in London and New York. Nasrin, the elder sibling, is a pilot who is adjusting to life as a stay at home mother. Meanwhile, Sabrina, the younger sister, is a tenacious workaholic making waves on Wall Street. However, when their father passes away suddenly, the sisters return to their family home in Wales. When Shamsur's will is read to the family, a long-hidden family secret is revealed, and the story unfolds from there.

Before I could ask about her literary influences, Nilopar enthusiastically brings up Jhumpa Lahiri during our conversation. She shares that she wanted to capture that Bengali immigrant experience with her book like Lahiri.

While reading the book, I was deeply moved by Nilopar's writing style, which focuses on the immigrant experience through both physical and metaphysical. The novel's prose is truly remarkable.

I caught up with Nilopar via Zoom, then followed by an email conversation in late April.

The Halfways spans across four cities: London, Wales, New York and Sylhet. What inspired you to write this particular book that spans across all these places, and how did you develop the characters and plot?

The Halfways is a big family story, but one which is complicated by the pull of another homeland, which is Bangladesh. It centres around the lives of multiple generations of the Islam family who own an Indian restaurant in the Brecon Beacons. When Nasrin and Sabrina's father passes away, they return to the Beacons to join their mother and cousin, Afroz. There they are confronted with a devastating secret that had been buried for decades. The novel follows these women as they try to navigate the fallout from the disclosure of this secret, and then a tragedy occurs that will change their lives forever. The focal point of the story is set in a fictionalised town in the Beacons where the restaurant, which is called the Peacock is located. But the lives of the characters will take the reader to Sylhet, London, and New York.

I've always loved big family novels. As microcosms of society, families allow an author to create a wide cast of characters who have their own agendas but are tied together by family connection. Family dramas are a great platform from which to deep dive into personal relationships and to navigate the gulfs between multiple generations, to explore the impacts of disparities in education and earnings and the differences in values and faith. One of my favourite family novels is Jeffrey Eugenides' Middlesex which is about three generations of Cal's Greek-American family, who travel from a tiny village overlooking Mount Olympus to Prohibition-era Detroit, before moving out to suburban Michigan. Like Middlesex, family novels about diaspora can span different countries, even continents, and that is exactly what happens in The Halfways. The story follows the different characters to the places they live—New York, London, Sylhet and Wales.

The Halfways grew out of an assignment that was set a few months into my MA in Creative Writing at London's City University. We were asked to write about a character waking up in strange circumstances, and I wrote of a woman who wakes up next to a young child into a world vastly different to the one she had woken up to before. I hung the scaffolding of my ambitions to write a sprawling family saga around this intimate scene of two people grappling with grief, and The Halfways unfolded around it—messily at first, and then with more conviction, revealing an abundance of characters and drama that shaped the Islam family's world.

What literary influences have shaped your writing, and how have they informed your approach to storytelling with this debut novel?

I am what I read, I think. I'm definitely influenced by everything I read and I read very widely! However, in writing The Halfways, I was somewhat motivated by the desire to represent a family heritage like my own. Being a daughter of first-generation immigrants from Bangladesh, it felt important to me to tell this story and to foster an understanding of the Sylheti Bangladeshi community in Britain, their food, their language and their customs. I loved finding a character like me between the pages of a book when I discovered Jhumpa Lahiri's Interpreter of Maladies. Her stories about second generation Bengalis living in the West filled me with an overwhelming sense of gratitude and relief. Protagonists like me existed! And they had wonderful stories to tell!

Over the coming years, I discovered Zadie Smith, Monica Ali, Yaa Gyasi, Mohsin Hamid, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Jeffrey Eugenides and so many more writers from whom I learnt how the universal themes in literature (for example, love, courage, freedom, family, faith, justice, coming of age) can be beautifully enriched by the specificities of ethnicity and culture.

The novel features Nasrin and Sabrina as the central characters who were raised in Wales but currently reside in New York and London respectively. Then, there's Afroz who grew up in Bangladesh. How did you research and prepare to write about the different cultures and settings portrayed in the book, and what challenges did you face in representing them authentically?

One of the challenges of using multiple perspectives was ensuring each voice was authentic and using research to build the individual worlds of each character. Nasrin and Sabrina are an amalgamation of women I know whose lives are characterised by the duality of being both British and Asian, but their careers required some research.

Afroz is also a character formed from the women I know who grew up in South Asia and came to the UK as teenagers or adults, either to study or after marriage. It was more difficult to imagine the lives of the older generation, and I had to remind myself of the universality of human emotions, regardless of time and place: even in Shamsur's childhood world of no radio or television, there was scope for fandom—if my nine-year-old could learn the words of her favourite Lady Gaga songs, why couldn't Shamsur learn the words of his beloved Lalon as he listened to wandering minstrels singing them as they journeyed through the village?

Researching Fakir Lalon Shah, a philosopher, singer and composer, took me down a rabbit hole: sifting through the abundance of academic literature on the Baul singer tradition from which Lalon hails was an arduous process. Furthermore, Lalon's songs were passed down in the oral tradition and finding consistent translations was difficult. Nonetheless, the research was important as Shamsur's character drew great inspiration from the bard's nomadic egalitarianism.

After creating the individual worlds of each character, the biggest challenge was orchestrating each of those character arcs to both transform the inner lives of the relevant character but also to coalesce under the larger themes of the novel: what happens when the ties that bind us are challenged? What happens when lies become the backbone of our relationships and we have to re-invent ourselves when the truth comes to light?

I wanted to give my cast of characters—the banker, the ex-pilot, the housewife, the restauranteur and the chef—an appreciation that their individual stories begin long before they are born and that in order to fully understand themselves, they must first understand their family.

You have mentioned that the setting for the restaurant, The Peacock, was influenced by your upbringing in the UK and your father owning an Indian restaurant. What other aspects of the novel would you say are most personal or meaningful to you, and how did you draw on your own experiences or emotions while writing the book?

I drew on my experiences as part of the Bangladeshi diaspora living between two cultures in order to write the book, and the Peacock is inspired by my father's restaurant, but all of this raw material was transformed in the writing process into a story that is completely fiction. Like the green murta plant which Elias searches for in the first chapter of The Halfways which produces the hand fan belonging to his mother but which no longer resembles it in any recognisable way; very little of my experiences which have gone into writing

The Halfways are recognisably "real". The many exercises we were set during my MA Creative Writing course encouraging us to experiment with voice, perspective, tense and distance, were tools of the writing process that freed my creativity so that it was no longer restricted to real life. The places I have depicted in the novel are dear to me—I have fond memories of my father's restaurant in Wales, and our annual family holidays to Bangladesh, and I have used my love of these places to depict the bond humans can have with a place. The themes of identity and belonging explored in the book are also issues which preoccupied me as a brown child growing up in rural England.

What themes or messages did you hope to convey through your debut novel, and how did you go about exploring them in the story?

The novel is named after an important theme in the book: the Islam family members reside halfway between places—some feel stuck halfway between two cultures, others feel trapped between conflicting expectations and values. I wanted to delve into these experiences which are not just specific to the British-Bangladeshi diaspora but are universal issues facing other diasporas around the world. I also wanted to explore both the potential for tragedy in diaspora life—that feeling that nowhere is quite home and the nostalgia for a place long left behind—but also how wonderful and uplifting migration can be, and how the courage to embrace new places can be a source of joy and aspiration. The immigration story is such a powerful and timeless one. People always move, seeking all varieties of freedoms: but they also yearn for a sense of belonging in the new places they call home.

Family expectations and the role of cultural, traditional and religious values in a person's life is also an important theme especially because there is such a disparity in attitudes towards these by different family members. The novel reflects on how, sometimes, lonely immigrants can uphold these old values and traditions as a way to feel attachment to their old worlds, especially where they haven't been able to assimilate but it also explores how the younger generations can break free from them, or find weaknesses in them, such as for example that noble deeds can't guarantee good outcomes.

Importance of story is a big theme too, and in fact it impacted the structure of the novel - throughout the novel, there are flashbacks to each of the character's pasts, and these flashbacks are told in a standalone folkloric style, reminiscent of someone telling you a story around a fire. The novel explores how Elias's sense of wellbeing is bolstered by his understanding of his family story and how he fits into it – these are the bones of his being, and they light his path in a way. And Riaz too, laments the fact that he does not have a braggable history like the Islams do—I think that a positively framed story can strengthen family bonds but also gives us something to shape our identity because the past shapes our present. This is true of community as much as it is true for a family.

I also wanted to explore racism—both external and internalised. Nasrin grapples with everyday racism from her neighbour whilst also struggling to always see herself through the brown lens she thinks her husband and the world perceive her. Sabrina has internalised racism, and she loathes in herself and in others behaviours which might mark them out as "others" in a Westernised world. I've always been interested in how racist behaviour can impact lives, and it's important to acknowledge that the enemy-thinking can be inside as well as outside.

Usraat Fahmidah loves philosophy. Her favourite philosophers include Simone de Beauvoir and Agust D. Send her book recommendations: [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments