Three literary walks: Nilanjana Roy, Shehan Karunatilaka, Daisy Rockwell

'Should a Books page be apolitical?'

"Can I be really blunt? Features sections by and large are handed out to women. That's the only reason it is seen as 'soft'."

Nilanjana S Roy has authored three novels, The Wildings, The Hundred Names of Darkness and this year's Black River, but it is The Girl Who Ate Books, her collection of essays on reading, which told me we would have much to talk about if we ever met. The hunch was right—as a columnist of books at the Financial Times' Life and Arts section, she tells me that "a book review gives a book a home, a place."

We have this conversation as she begins to leave the Bangla Academy on the penultimate day of the Dhaka Lit Fest. She had said something in her session on 'Culture Wars' a day earlier which struck me—how Books pages are (incorrectly) expected to be the "unpolitical" part of a newspaper. Could we talk about it? She suggests we take a walk.

"In India and in the UK, the moment people started to realise that Books pages are the 'ideas' pages, they started to be passed back to male editors. And then again you have to fight for your space", she says as soon as I bring the issue up.

We delve deeper: "What you're doing with a Books page is creating a running history of the ideas and the parallel history or the imagination of a country. You're not looking to question and knock the book out of attention as much as you're trying to say, What kind of creature is this? Of what family? What tradition?

How do you make those choices?

"Your own opinion doesn't matter. If you're reading a book with a certain sense of disgust or discomfort—the latter is fascinating, because why is a writer making you so uncomfortable, what is he or she pushing past? Such as Hanya Yanagihara; I read her before the hype started. It was extremely disquieting. At the same time, you see that she's writing in the tradition of Thomas Hardy and taking that and putting some nails in the coffin. Your review is not going to be about how it made you uncomfortable. It's about what this is conveying to you. What are you participating in? So, with reviews it's about paying attention to your instincts and then not being carried away by them. Knowing your strengths and limitations.

There's a certain kind of book that I step back from. I know this is going to be a bestseller but I don't have a liking for it. I'll tell my editor that this isn't for me. On the other hand there are books that I don't review when I'm too close to them. I don't review friends' books because I know about their crises. I don't review a lot of Indian books. Having said that, I recently wrote about Meena Kandasamy's The Book of Desire for my FT column. But while Meena and I respect each other's work, we've only met 5 or 6 times, we're not intimate friends.

One of the most important things for Books editors is the calendar. If you don't get the calendar right at the start of the year, you will lose books. You won't have a sense of perspective. One of the things that you owe your readers is that you can't be a slave to bestsellers but you can't have just your own snobbery dictate things. So what are the most impactful—I hate that word—what are the most powerful, resonant works?"

How do you pair books with the right reviewer?

"That's an art. There is full disclosure between editor and reviewer—you try to avoid family squabbles and people who have or are going to sleep together.

I look for something that is seen as non defensive expertise. So not the expert who is going to resent anyone who has come up only because they're poaching on their reserves. Somebody who is generous with their expertise and yet is dispassionate enough to not get carried away. It's tricky. Take Deepti Kapoor's Age of Vice. It has to be reviewed by somebody who knows Delhi, but not by somebody who knows Deepti and Delhi. Either that or you can have a personal essay.

You can't break the reader's trust. The most important thing is understanding that you're writing to some extent to whatever the tradition of your paper is. You're not really writing for the publisher or the author though you do respect the expertise or the craft of their vocation."

How do you decide who your readers are?

"With the FT, readership is global. It trends up age-wards—in the rest of the world it actually trends really young. You can't be club-ey—you can't write a review of one of the great London authors with in jokes and references. You just have to be aware of how wide [your readership] is. If you can simultaneously write for the reader in Dhaka and a reader who is out in one of the smallest villages you can think of but who picks up The Daily Star, somewhere in there is your sweet spot.

If a review is unjust, you know it. The trick I've had to learn is—don't restrain genuine enthusiasm.

I don't think people realize how intense book-reviewing can be. You have to get your pages packed, you have to think of ideas. A lot of us are also used to reading at speed. You have to readjust and realise the reader is not going to be reading at that speed. There's only a certain kind of book that can absorb a book at speed and judge it for all time. So good reviewers—you nurture them like gold."

What function does the book review serve today, particular for a general audience where it's not about literary criticism?

"If you want to catch eyeballs, Instagram and TikTok do that better. A review also is a piece of writing. It's not just about the judgement. I keep telling people to read Parul Sehgal's reviews. Look at them, strip them down, go sentence by sentence and tell me how much work has gone into them. Just see how much she's packing in there and then also making it readable. It should be a joy to read.

You shouldn't take sides. I don't know of a single Books page that doesn't have the right values. Think of the origin of the word 'politics'--polis. People. It comes back to who you're writing for. The reader. What do books mean to you?

Otherwise it can be like London Review of Books or New York Review of Books, which is that 'we set the standard'. Or something more like 'We cover everything'. FT's coverage leans very heavily towards nonfiction. But the fiction is carefully selected. We almost never run negative reviews of fiction. It's not that anybody's told us we can't. We do a limited amount of fiction and therefore every book has to count.

I can tell immediately when a reviewer is bored."

We talk some more about the intense process of writing book reviews—the art that goes into crafting each of its sentences, but the snarl of Suhrawardy Udyan's traffic takes over as Nilanjana Roy exits Bangla Academy, and I turn back.

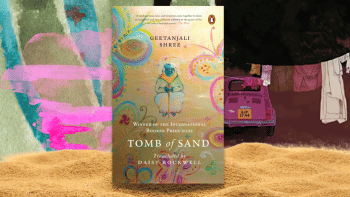

'Like sourdough, Tomb of Sand continues to expand'

Another day, another hectic exit from the Bangla Academy auditorium. There is daylight this time, so the interruptions are more energetic, as hordes of readers want their copies signed by Daisy Rockwell, te American translator of Geetanjali Shree's 2022 International Booker Prize-winning Tomb of Sand—the first novel in a Hindi language to win the prize.

Daisy Rockwell hasn't stopped smiling for days. She tells me she doesn't care if we run late, or if we stop to talk to people, as long as her daughter walks with us. "She must be exhausted because she's heard me talk endlessly about the same book."

But the text certainly merits it—written first as Ret Samadhi, Shree's novel follows Maa as she freezes shut upon her husband's death, and rises open again to revisit the spaces she left behind during Partition, finding, along the way, love, friendship, a new voice.

What brought you to translating Hindi and Urdu?

"I started studying the languages in college and just fell in love with first Hindi—I felt a strong urge to translate it", Daisy Rockwell says as we wade through the walkway bordering the Bangla Academy pond.

"I took a course with AK Ramanujan, the famous translator, and he encouraged me to do more translations."

Since then, she has gotten a PhD in South Asian literature and translated iconic works of literature written in Hindi and Urdu, alongside painting under the alias of Lapata (missing).

One can't help notice the difference in size between Ret Samadhi and Tomb of Sand. What has it gained in translation?

She laughs and holds up the two paperbacks—one double the size of the other.

"Part of the reason is that for the first English edition, they do all of the books in the same page size at that publisher. So it's a shorter page than the Hindi and that makes it go longer. The Hindi publishers are trying to save money on paper. For the English I put in page breaks.

So it's the same book, but our book is very expansive. When it came into English it expanded and then it got the Booker prize and our lives expanded. It's like sourdough, it's growing and growing."

In your session with Rifat Munim, Geetanjali Shree spoke about how some of the objects in the book (the door, the wall) had turned into characters. But the characters, like Maa, had also turned into objects. How did you work with that as a translator?

"It's actually very tricky because sometimes you're not sure if it's the door or the person that Geetanjali is writing about. In Bangla and Hindi, you can leave out the subject of the sentence. It's somewhat clearer in English, but I still had to maintain that ambiguity in English as to whether it is a door, or a back, or a person thinking. Sometimes even I myself wouldn't realise that it was the door until a few drafts in. If you as a translator are surprised, you have to try to surprise the reader."

You talked about how tedious the process of translating and editing was. What helped retain the pleasure of it?

"It's like going through a forest until you suddenly come to a clearing. You just have to keep slogging and then suddenly it starts to come alive, and then you interact with it very differently when it becomes an English text that you're editing.

The beginning is joyful and the end is joyful. Translators have to be very patient people", Daisy Rockwell concludes before she, too, is lost in the crowd.

'Until you have a voice, the writing doesn't exist'

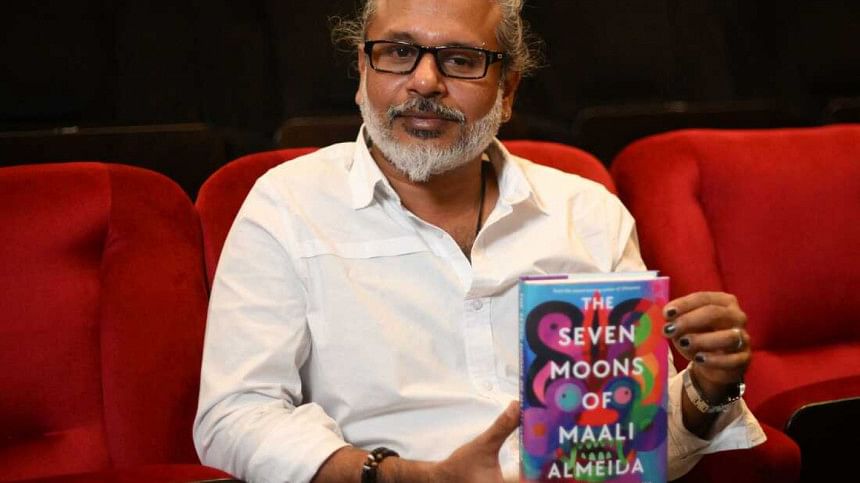

That Shehan Karunatilaka is approachable has been the topic of conversation among most DLF visitors this past week. We've seen him unwind on the grass, stroll through the stalls, signing copies of his 2022 Booker-winning novel, The Seven Moons of Maali Almedia, and posing for photos with fans even when the queues seemed to become unending. And so there I was at the exit to the auditorium again, after sunset this time, hoping to score a hattrick with these literary walks. The Sri Lankan author of fiction and children's books—who by day works in advertising—decides to change things up. At his suggestion, we make a silent beeline for the parking lot and find two chairs in an abandoned, parrot green book stall.

Seven Moons splits the protagonist from his own voice, gives his ghost the power to whisper into ears, hovering over people's shoulders. Why do voices interest you so much?

"For work I write websites, feature articles. I can have a plot, or I might have an idea and I can keep writing around it, but until I find a voice I don't consider it a project."

You've talked about how writing the book as a ghost story was a safe choice. Did you orchestrate it in any way that it reflects more contemporary issues of Sri Lanka?

"There is a character called Rajapaksa. This is a delicious fact that I found—that in '89, Mahendra Rajapaksa was a human rights activist who was going to Geneva with the mothers, holding up photographs, saying that these are the atrocities my government is doing. And I put that in because it was historically accurate. One of the characters says, Let Rajapaksa run a war, let's see how he does. It's ironic that I'm looking from the future talking about this.

I was very clear about my novel Chinaman, that it was based in 1996-1999. Purposely I didn't watch any modern cricket when I was writing that. Same with this—I kept it to 1990. Now it's going to be read in 2023 and people are going to look for parallels, but I don't know if I planted any clues on purpose."

The tug of war between forgetting and moving on drives the novel forward. For you as the author, was it also about remembering these events in Sri Lanka or processing them and moving on?

"It was supposed to be an amnesia tale, like Jason Bourne. Maali remembers bits of it and it comes to him in bodily aches. But then it also became a revenge tale and a love story. It was also about how much Sri Lanka remembers and forgets."

Do you have any advice for independent writers to navigate censorship in South Asia, since you were able to do that with your book?

"Someone asked me, why don't your detective stories have no detectives? And I thought that in our part of the world, our detectives are useless. Our cases, our murders are unsolved or repressed. So it seemed fake for me to invent a Poirot or Sherlock Holmes for Sri Lanka. It seemed more realistic that it's the journalist who unearths the truth, puts themselves in danger and sometimes pays the price. So my self-preservation technique is that I hide behind fiction."

Finally, any literary ghosts that you think are or should be hovering your shoulder?

"Uncle Kurt Vonnegut is always the ghost that is in my ear. So the great writers perhaps. But other than that, no, I don't want to hang out with ghosts!"

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor of Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected] or @wordsinteal on Instagram and Twitter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments