Geetanjali Shree's 'Tomb of Sand': A woman and her many borders

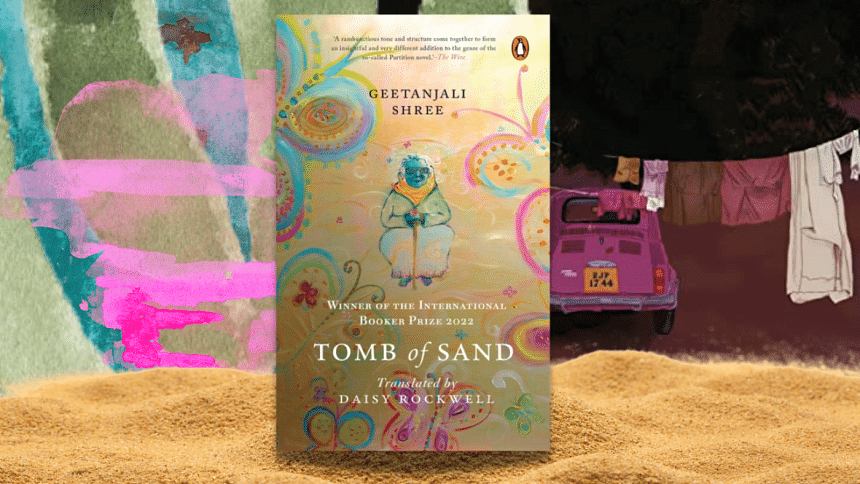

There are people who rush to read the winners of literary awards. I'm not one. But I made an exception this year. When I learned that Tomb of Sand (Penguin Books, 2021), Daisy Rockwell's English translation of Geetanjali Shree's Hindi novel Ret Samadhi (Rajkamal Prakashan, 2018), won the 2022 International Booker Prize, I immediately ordered the book from London.

I was excited when it arrived. A bit daunted, though, since it's 735 pages long. I found a park bench nearby beneath the train tracks, and while trains ran overhead, people walked, jogged, or bicycled past me, a few people occasionally throwing a glance at a person reading a book on a bench—two of them even remarking with joy at the sight—I finished Tomb of Sand in six weeks.

What a thoroughly enjoyable read. If you're someone who reads for a rapidly-moving plot, this book may not be for you. There is a plot embedded here, but this novel is so much more: a long, winding journey, centred on a family, with acute eyes on love and distances within a family, but also through language, Partition and imposed borders, and so much more. There's sadness, foreshadowed right in the opening pages, but there is so much keen and delightful observation. And much humour.

The book opens with an apt description of what your reading experience will be: "The story's path unfurls, not knowing where it will stop, tacking to the right and left, twisting and turning, allowing anything and everything to join in the narration."

The story is centred on a family in Delhi, with the focus on 80-year old widowed Ma. The book opens with Bade, the eldest son, retiring and preparing to move from a government-provided home to a private house. In the midst of the chaos, Ma disappears. She will be found wandering, and the family agrees to let her move in with Beti, the daughter, who lives by herself in a somewhat unconventional lifestyle. There under the cautious eye of the daughter, the mother recovers and builds an engaged life with Rosie, a hijra friend of many years who treats her as a sister. After a series of crises, the final part of the book opens with Ma deciding she wants to visit Pakistan, and Ma and Beti cross the border. The pair go off on a journey that takes them through Lahore, the Thar desert, other destinations—a trip both in geography and vivid memories of Partition time—and they end up in Khyber.

The plot had enough surprises to satisfy me, but the special joy in the book was in the meanders. At one point you read pages about the tinkling of bangles on Ma's wrist keeping Beti awake at night, worrying about Ma's fragility, and you can yourself palpably feel the unease. In other places, you read a reflection on doors, the doors of eldest sons' houses being in a sense permanently open. Borders, for sure. No surprise, since the opening page promised, "This particular tale has a border and women who come and go as they please. Once you've got women and a border, a story can write itself."

The meanders to me, as a reader, sent me on my own tangents. I found myself stopping to reflect on my own doors, not those of an eldest son, but of a wanderer, someone who's moved and lived in several dozen rented apartments. What did those doors signify to me, to those who lived with me or those who visited? Borders happen to be one of my own preoccupations and I contemplated borders of language, borders between men and women, between elders and those younger, between classes.

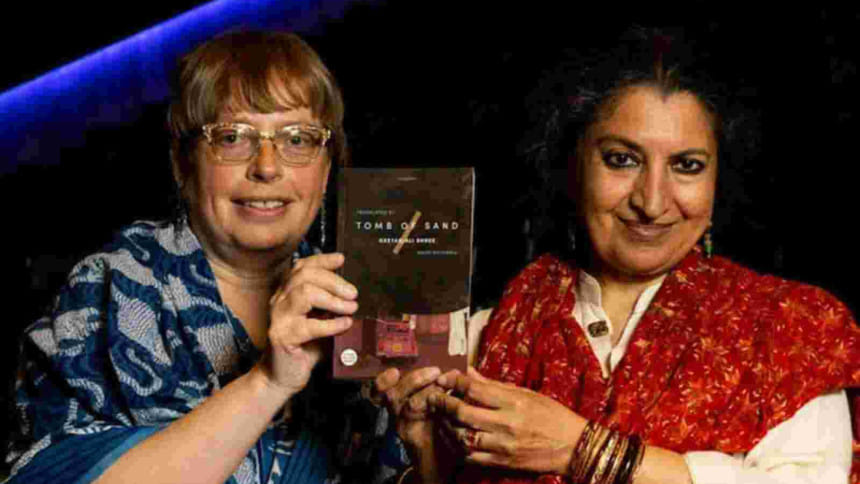

The other delight in the book is the language. I marvel at how Daisy Rockwell translated this one-of-a-kind novel. She pulled off a unique transformation. In a few cases, she leaves some Hindi, in other places she creates Hindified words in English. She mutates wordplay. Not knowing Hindi, I missed a few things but those were solved with Google. The book is eminently readable for someone with no knowledge of Hindi. There are many cultural, literary, and political references, and it helped that I knew most of those. The way Rockwell translated this book, you also end up taking pleasure in the multiple language echoes of the subcontinent. In her translator's note, she writes: "I have striven throughout my translation to recreate the text as an English dhwani of the Hindi, seeking out wordplays, echoes, etymologies, and coinages that feel Hindi-esque." She succeeded quite marvellously, and it would be fabulous if Rockwell could use this experience to write or teach some craft lessons to share with others who translate from South Asian languages.

Mahmud Rahman is a writer and translator who currently lives in California. His first book, Killing the Water: Stories, was published in 2010 by Penguin India. His second book, a translation of Bangladeshi writer Mahmudul Haque's Partition-centred novel Black Ice, was published in 2012 by HarperCollins India. For more on Mahmud's writing, visit www.mahmudrahman.com.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments