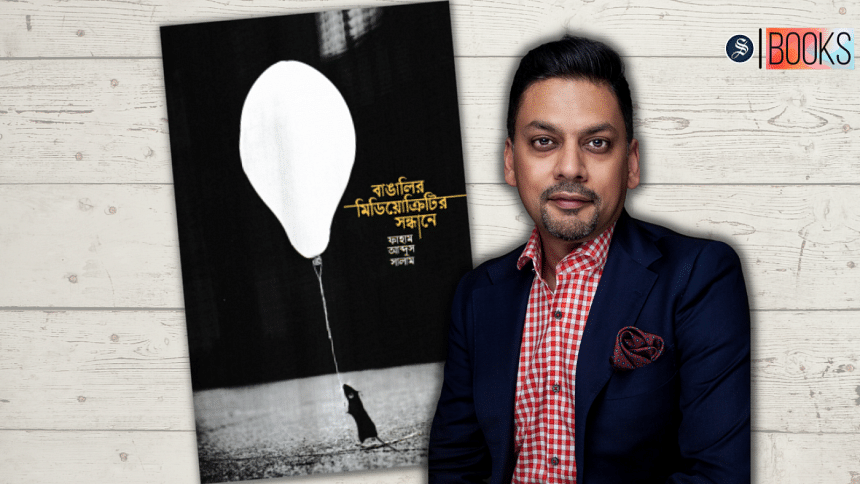

Why I disagree with ‘Bangaleer Mediocrityr Shondhane’, the book that got Adarsha banned from Boi Mela

The recent fiasco surrounding three books published by Adarsha has caught the public eye after the publishers were refused a stall at Boi Mela this year. One of the books, Bangaleer Mediocrityr Sondhane (2022) written by Faham Abdus Salam has received special attention as Bangla Academy has specifically flagged it as vulgar. The book itself is essentially a collection of philosophical polemics, which sometimes take the form of politically charged rhetoric. I object to the book on entirely different grounds than that of the Bangla Academy.

I believe that there is no reason that this book should be restricted, but I have serious concerns about some key points made in the book and their underlying philosophy.

Where Faham Abdus Salam calls Bengalis mediocre, in my soon-to-be-published book, Before You Shame My People, I see Bangladeshis as a highly promising nation of tortured people who, at the same time, have dissented against and been crushed by the powers of colonialism, imperialism, and an ancestral and oligarchical political system.

The author and I reach the same conclusion in our books, but our narration differs. He says that Bengalis have become a state before they could become a polity. Their place in that state has become that of subjects and not citizens. I admit that our state has reduced us to subjects and we have been excluded from the structures of citizenry; but that is not the people's fault. The blame falls squarely upon the system that has been inflicted upon us. The people should not be put on the stand, the system deserves that place.

It's true that Bengalis have not been able to become a citizenry. But is that a failure of the people, or were they denied the opportunity to become citizens by the colonial power structures that have remained undisturbed even today? Did Bengalis not fight for change? Does the idea of citizenship remain limited to that of Western neoliberal citizenship? When supreme sacrifices have been made repeatedly, how can one deny that the people of this land have fought to become citizens?

It is a matter of great misfortune that we have been forced into being subjects of the ruling class for centuries. Once the foreigners left, it was local politicians who took up that mantle. But that doesn't mean we want to be subjects or that this life satisfies us. Our fight against it is still going on. Fulbari, Chunarughat, Rampal, the quota protests, the road safety movement—they all point towards that fight.

The author has pointed out other flaws in Bengalis, but his explanations suffer from a lack of depth. According to him, Bengalis don't understand that the legal code has a purpose beyond punishments. But what is the reason behind that? Do Bengalis come out of their mother's womb with the "fashi chai" slogan on their lips? No! They are driven towards a punitive understanding of the legal system by the socio-political realities surrounding them.

When they see that the court system in their country is against them, when they see governments using the police and administration against the common people, they are forced to become vindictive. The system births the mentality and it is not the other way around–because the system is a ghost of our colonial past, it is not the fruit of our own democratic process. Our democracy has been stuck in limbo for centuries.

Another problem apparent in Salam's writing is his love for the West. In his book, he has put the liberal thoughts of the West on a pedestal. His discussions convey the idea that there is nothing better than Western liberalism, that we must copy that liberalism for ourselves. This is an imperialist line of thought, or in simpler terms, it serves the agenda of NATO. He is right that even though we are used to a "modern" lifestyle, we still allow archaic, tribal ways of thinking. But what is the direct problem in that? In my upcoming book, I have put liberal secularism and individualism on the stand. Is individualism the be-all and end-all?

Our collective coordination, our culture, our history–they all help us as a tool in our fights. This minimal coordination has been what has allowed us to revolt time and again. Our sense of community is our strength. We can only stand with each other in times of trouble, we can only fight for each other because we are communitarian. I have lived in America and I have seen that they lack the level of amity we maintain amongst ourselves. This may be my personal opinion, but from what I have seen, if someone gets on a bus that has one person on it and is otherwise empty, they will never go and sit beside that person; they will take the furthest possible seat.

Another thing that has come up in the book's discussion is the distance between society and the state. The author has tried to say that the collective unity of Bengalis runs into obstacles in society, not at the level of the state. He has also said that Bengalis gained a state before they could grasp the idea of collective ownership. These claims have historical flaws.

Collective ownership was definitely a familiar concept to the farmers of Bengal. If that weren't the case, they wouldn't have fought for land rights—they would not have stood up against indigo planting; they would not have held their ground against the landlords and their enforcers with unparalleled courage. The fact that they could do it proves that they were conscientious not only about their individual benefit, but also about the collective and societal benefit. And if we are going to talk about the divisiveness in society and state, then society must be stronger than the state, so that it has the ability to pull the reins on the state. The state is only an instrument meant to serve society. It is natural that society will mean more to an individual than the state. In fact, it's natural for a state to contain more than one society.

The author's most problematic statement is this: "He can't live without freedom, but he doesn't deserve a state."

A state isn't something so great that a person needs to earn it. A state isn't a lollipop that we wanted dearly and that the British Raj bestowed upon us. If colonisation had not happened, then we would have come upon a liberal state by ourselves. The state is only an institution that is supposed to safeguard the interests of society. In that sense, of course we deserve a society. We can ask whether this state serves society as diligently as possible, but the question of deserving society is no question at all. It's like saying the entity that has allowed the state to exist, deserves it.

Some of Faham Abdus Salam's discussions in the book definitely deserve praise. He has successfully captured the importance of revolution. Freeing society from a particular party isn't revolution; it is the natural course of change, he points out. Revolution can only take place when a party's journey towards becoming a dictatorship is stopped and when that mentality is reached collectively. He is not of the opinion that 1971 was a revolution. In fact, he has tried to say that we may have enjoyed more freedom under the Pakistanis than we do now. This is a brave statement and in many cases, completely true. "Replacing the Punjabis with Bengalis isn't revolution, it's politics"—is a sentence that is especially deserving of praise.

His discussion captures a love for the West, but at the same time, it has surprising postcolonial sentiments. He tells us we need to be more like the West, but also gives us the indication that we need a proper revolution of our own. I would have agreed with him, if he didn't put the blame of this reality on the shoulder of Bengalis, inadvertently absolving the structures of state and power.

Anupam Debashish Roy is an editorial assistant at The Daily Star.

Translated by Azmin Azran.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments