The resurgence of political cartoons

Political cartoons highlight contemporary events and expose societal anomalies with a sharp focus. These cartoons have played a pivotal role in this region since Pakistani rule. This tradition continued in independent Bangladesh, maintaining its significance over the years.

Even just over a decade ago, political cartoons criticising political parties, leaders or heads of government were a common sight in Bangladeshi newspapers. These front-page cartoons both provided comic relief and delivered powerful messages, silently protesting against injustice and corruption.

This is the true strength of cartoons—a single illustration can resonate with the masses more effectively than a thousand words, rendering this art form timeless. However, this powerful medium of protest has gradually diminished over more than a decade, to the point where it has almost disappeared entirely.

During the era when political cartoons thrived in Bangladesh, icons like Zainul Abedin, Quamrul Hassan, Qayyum Chowdhury, and Rafiqun Nabi (Ronobi) used their art to illustrate societal disparities with strong political commentary. Artist Shishir Bhattacharya played a pivotal role in transforming the portrayal of political cartoons in newspapers, receiving much acclaim. Inspired by their predecessors, many young artists took up cartooning, evolving it from a hobby into a profession. These artists produced impactful political cartoons, some of which appeared as serialised works.

Starting in 2008, the evolving political framework in Bangladesh started to bring about gradual changes to the situation. The country's position on the Reporters Without Borders' Press Freedom Index dropped from 127th in 2010 to 165th in 2024. Just as the practice of independent journalism has faced constraints, the art of creating political cartoons has also been stifled. Fear of lawsuits and harassment has deterred newspapers from publishing cartoons that directly critique the ruling party or its leaders—not just on front pages but on any page at all.

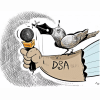

Cartoonists, too, were gripped by the fear of imprisonment under the heavily criticised Digital Security Act (DSA), which was rebranded as the Cyber Security Act in 2023, as well as the threat of defamation cases filed by ruling party members or their loyal lawyers from various corners of the country.

The arrest of cartoonist Ahmed Kabir Kishore and writer Mushtaq Ahmed under the DSA in 2020, followed by Kishore's detention without bail for 10 months and the subsequent death of Mushtaq in custody in 2021, plunged political cartoonists in Bangladesh into a state of profound fear and anxiety.

On July 16 of this year, Nieman Reports published an article titled "As Press Freedoms Erode in Bangladesh, Political Cartoonists Are Being Targeted by an Increasingly Authoritarian Regime" by Sheikh Sabiha Alam, shedding light on how political cartoonists in Bangladesh, much like the press, had become targets of an increasingly authoritarian regime. Shishir Bhattacharya was quoted in the report saying, "You can't draw with the tension brewing in your head that you may land in jail anytime and spend the rest of your life there."

This was how political cartoons and cartoonists in Bangladesh remained shackled for years.

However, the July uprising in 2024 marked a turning point. Casting aside years of silence and fear, cartoonists began wielding their art as a tool of protest. During this student-led mass movement, everyone from amateur enthusiasts to professional cartoonists contributed their work. Braving their fears, millions shared these cartoons on social media, amplifying the strength of the uprising. The works of cartoonists like Debashish Chakrabarty, Morshed Mishu and Mehedi Haque, among others, inspired courage and resilience among the people, giving the protests a newfound vigour. Cartoons drawn on walls under the cloak of night etched themselves deeply into the hearts and minds of the people. According to the Bangladesh Cartoonist Association, more than 500 cartoons were created during the July uprising.

The immense challenges faced by cartoonists during that turbulent period have been shared by many in hindsight. Cartoonist Fahim Anzoom Rumman recounted his experience, "I had to remove all of my information from my page. I was bombarded with emails trying to find out my location." Similarly, young cartoonist Natasha Jahan had to go into hiding after drawing cartoons during the movement. Her ordeal was highlighted in a report by The Daily Star on September 3, "Plainclothes police visited my home to gather information. Since then, I've been living elsewhere. From there, I continued drawing cartoons and attending protests. Despite the risks, we kept drawing—for justice and our country."

After the government's fall on August 5, the Bangladesh Cartoonist Association, Drik and earki collaborated to organise an exhibition titled "Cartoon Ey Bidroho (Revolution in Cartoons)" at Drik Gallery in Dhaka. The exhibition showcased nearly 175 works by 82 cartoonists.

During the previous government's tenure, the few cartoons that managed to appear in newspapers, despite countless threats, were largely symbolic. They refrained from directly depicting the faces of ruling party leaders or the head of government. The July uprising not only restored freedom for cartoons and cartoonists but also brought political cartoons back to the front pages of newspapers, who are once again boldly publishing cartoons that explicitly portray political figures, including their faces. The hope now is that this resurgence endures, ensuring that political cartoons and freedom of expression can never again be silenced in Bangladesh in the future.

Zareen Tasnim is sub-editor at The Daily Star.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments