Why I still love Roald Dahl’s ‘Matilda’ today

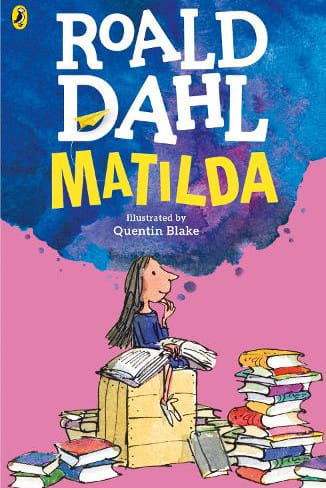

Roald Dahl's best-selling book, Matilda (Jonathan Cape, 1988), turned 25 back in 2013. This year, the book's film adaptation, released on August 2, 1996, reaches the same milestone.

Over the years, Dahl's work in children's literature has amassed quite the legacy in pop culture, with actor-director Danny DeVito's silver screen adaptation of Matilda only adding to the novel's popularity. Looking at the anniversary today, I can't help but wonder if the magical children's icon from the late '80s can continue to exert the same amount of influence over young minds.

Fourth-grade Rasha would have gleefully said 'Yes' in a heartbeat, but as a young adult, I believe there is some reflecting to be done.

Dahl never intended to work in children's literature—bit of an unexpected discovery there on my part, considering Dahl's popularity in the genre. It turns out that the iconic Matilda, much like the BFG and Willy Wonka, were products of the bedtime stories Dahl had curated for his children. In a BBC interview in 1972, Dahl stated that the stories in question were often poor in quality, but did occasionally intrigue his children enough to ask, "Tell us some more about that one." Little details eventually evolved to fictional world building and characters, and soon, literary favourites were born, starting with James and the Giant Peach (Alfred Knopf, 1961). Matilda, however, Dahl's final novel before his death in 1990, was born more out of a sense of acute paranoia rather than a father's efforts to put his children to bed. Through Matilda's story, Dahl had hoped to keep the love of books alive in a world that he thought was falling out of love with literature. As an ardent fan of the novel, I'm proud to announce that the late author largely succeeded in this endeavour.

Throughout Matilda, bibliophilia is maintained as being Matilda's most distinguishable characteristic. But there's much more to her than just being bookish. At a time when children were growing up with one-dimensional Disney princesses, Matilda Wormwood stood out as a child who spent her days diligently finishing her homework while tormenting adult-bullies in her free time. Matilda wasn't written as a saint-like figure for children to look up to. She was a girl who left no stone unturned in giving one back to her bullies, be it the abusive headmistress at her school or her crooked father running an illegal car business. Most importantly, Matilda made no apologies for who she was as a person. This is not a sentiment which appeals exclusively to '90s children only, but just about everyone who has been on the receiving end of bullying at any point in their lives.

The narrative revolves primarily around themes of authoritarianism, bullying, and abusive behaviour. To better illustrate these issues, Dahl presents supporting character Miss Honey's story alongside Matilda's, with the former mirroring the latter. Both characters are shown to have grown up in the care of neglectful guardians. What sets Miss Honey apart is her independent lifestyle, which in turn inspires Matilda to seek out the same for herself. As the novel progresses, the two characters form not only a mentor-pupil relationship, but also a mother-daughter bond, which then becomes legalised when Miss Honey adopts Matilda at the end of the story. The happy ending might come across as predictable, but what really matters here is the wholesome and heartfelt exploration of a mother-daughter dynamic shared between an elementary school teacher and her student. It's definitely what mattered to nine-year-old me, who was lucky enough to have a caring teacher much like Miss Honey, to help her stand her ground against bullying peers at school. Being able to draw that parallel with a complex fictional character who didn't put up with abusive behaviour—it meant the world to me back in fourth grade.

Approaching adulthood has been a bitter experience for most people of my generation. It'll hardly be a surprise if our collectively-growing sense of pessimism manages to override our fascination with fictional characters entirely, causing us to dismiss them as mere figments of our imagination. I'd expected a similar fate would be in store for the fictional Matilda, but it appears I have been proven wrong. The political undertones of Matilda haven't been lost on readers and viewers, even in the present day. Roald Dahl's final bestseller is recognised as a feminist tale rooted in queer culture. It was the protagonist's choice of going against socio-cultural norms that made all the difference for readers. Matilda Wormwood looked for solace in her collection of books, as a method of coping with the rejection she faced from her own family, and the society at large for not fitting into the conventions of an American girl. This served as an essential plotline in the novel, providing insight into the concept of 'disidentification', a practice adopted by members of the LGBTQIA+ community looking for queer values in stories which do not directly incorporate them.

I won't say that looking back at Matilda as an adult is a pleasant experience through and through, since Dahl's work does have its fair share of flaws. Miss Trunchbull, for instance, is portrayed to be a cruel and maniacal authoritative figure. While Dahl's logic is sound, the misrepresentation of non-conformational female athletes in a popular children's book can come across as problematic. The novel's tendency to reinforce the concept of 'revenge fantasy' in children's minds, with Matilda indirectly taking up the mantle of vigilantism, only adds to the concern.

Matilda's darkly comic theme undoubtedly makes for an entertaining read, but considering the novel's status as a children's book, the approach overall comes across as less-than-ideal for a school-going child. One might even wonder why telekinesis factored into the story, when Matilda's identity as a prodigy should've sufficed in helping her attain independence; especially given that her telekinetic abilities often prevented her from developing as a team player with her friends. Eventually, it is her superhuman abilities, rather than her intellect, which paves the way for the happy ending in a narrative heavily grounded in the reality of authoritarian culture.

I cannot, however, ever deny the comfort I found in this book as a bullied child; the same, I imagine, as every other bullied child who found their way to Dahl's iconic protagonist. Sometimes, all the things we have learnt as adults, all the complexities between right and wrong, all glide off, and the most base feelings are the ones we trail after. Then, and even now, Matilda holds a generosity of compassion seldom can match—and in that book, and its splendidly delirious adaptation, I found more than I could have asked for.

Rasha Jameel studies microbiology whilst pursuing her passion for writing. Reach her at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments