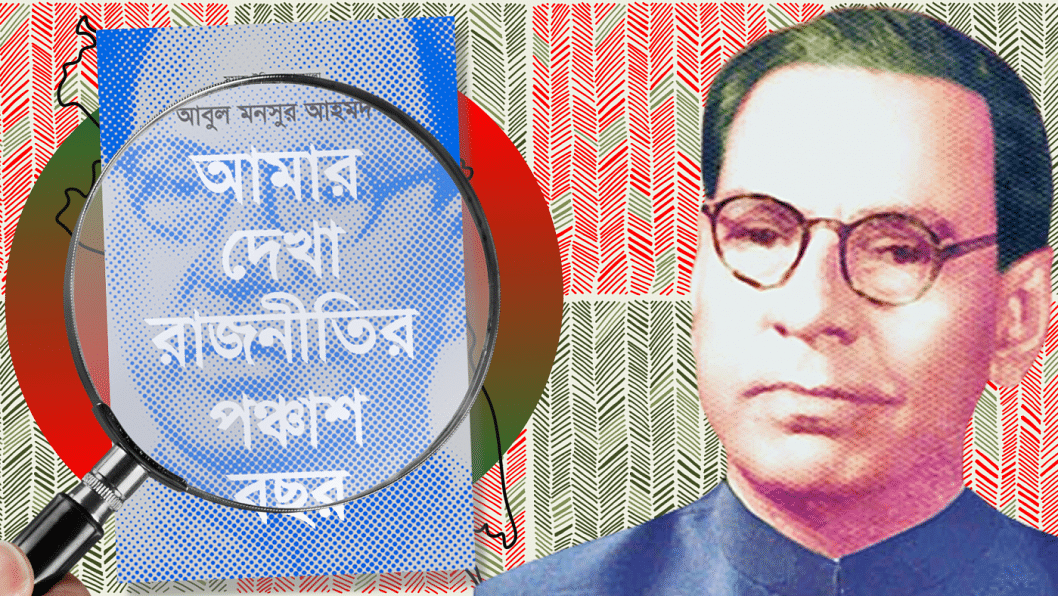

Within the narrative folds of ‘Amar Dekha Rajnitir Ponchash Bochhor’ by Abul Mansur Ahmad

Abul Mansur Ahmad grew up during a time when the legal and political parameters of our community, particularly for Bengali Muslims, were being framed. He wrote about topics that are dominant discourses even today, in the time and space which we now inhabit, and in the proposals and programs within which we operate. This is why he remains so relevant.

Ahmad was a positivist and a pragmatic. He was always firm and clear on his stances, and it is through such a perspective that he viewed and analysed the topics of which he wrote. Others have called this quality honesty. I like to call it conviction. His convictions lent his writing clarity; clarity brought them closer to "truth".

Theories of reading and text are my areas of expertise—it is from this lens that I would like to offer some formulae for reading the works of Abul Mansur Ahmad, particularly his memoir, Amar Dekha Rajnitir Ponchash Bochhor (1969).

We will, of course, look at this text as a narrative—what in Bangla we refer to as a bayan or biboroni. A narrative is shaped by events taking place in a particular time. Abul Mansur Ahmad, in Amar Dekha Rajnitir Ponchash Bochhor, selected prime events to offer suitable titles for chapters and sub-chapters of the book, and thus ensured that readers would perceive that particular time in a rather smooth way. This also allowed Ahmad to achieve a narrative smoothness, and coherent transitions, in his text.

We know today that every narrative, no matter how objective it seems, has its own tones and tunes which bear the author's subjective assessment on the narrated issues. This is present in this memoir, but on top of that, Ahmad's narrative in this book is particularly interesting because of his focus on what he referred to as kaltamami—a review and analysis of the historical events he recounts. All these narratives and analyses are grounded by reason, but not by theory.

Throughout the history he relates in this text and elsewhere, he is present as a pragmatic observer. His language is clean and simple. And so the reader can understand the text without having to struggle too hard, even though Ahmad's ideas are in fact deeply, deceptively complex. It is reminiscent of the writing of Nirad C Chaudhuri. We can mention here that among the political and cultural texts produced in Bangladesh, Amar Dekha Rajnitir Ponchash Bochhor is the most widely referenced in local and global academia.

One of the other significant features of the book is the utmost centrality of the author himself. No one other than Rabindranath Tagore, as I have stated elsewhere, could have authored the novel Gora (1910)—one cannot simply approximate the events recounted in the book, one has to have experienced them from the central position that Tagore was situated in. Similarly, Amar Dekha Rajnitir Ponchash Bochhor could have been written only by Abul Mansur Ahmad.

Very few individuals enjoy the opportunity of being in such central roles, and for such long stretches of time, as those occupied by Ahmad. This began from a young age, when he joined the Krishok Proja Party as a veteran organizer, with his political ideology eventually shaped by British-Indian politics and particularly the political process of Congress.

He then ascended to the power-centre through the politics of the Pakistan movement and Muslim League, the Awami Muslim League and finally Awami League. Even after leaving active politics and until his last days, he had the opportunity to maintain a very close and pivotal connection with all the political parties and state-related activities. These positions allowed him to take on the role of a political philosopher in his memoir.

Consistently, throughout the text, Ahmad presents his philosophies for readers, though not at the surface level. It seems that the text manages some crucial complexities and dialectics in a very coherent, implicit way. One of these might be narrated as the contradiction between theory and practice. Secondly, he was persistently aware of the relationship between the universal and particular.

Once, in the first essay of his famous book, Bangladesher Culture, he defined marvelously the universal as 'civilization', while equating 'culture' with the particular. In his narrative, however, Ahmad always prioritized practice over theory, and between the universal and the particular, he has always put more emphasis on the particular. In the deeper layers of the text, both theory and the universal play important roles.

At first glance, it seems that Abul Mansur Ahmad is describing and evaluating political events only, as they unfolded. Through a more conscious reading, however, readers come to realise how the explicit particularities are built on implicit theories of both the political and politics. Amar Dekha Rajnitir Ponchash Bochhor unfolds a very complex process of how the people create cultures, how cultures create political orders, how orders lead to the formation of political parties, how these parties engage with political activities, and how this in turn shapes the central powers in a state.

If we want to understand anything about politics from Abul Mansur Ahmad's political memoir, it would be that Ahmad conceived of party activities as part of a democratic state structure. The state-structure must reflect the cultures of people, and it will do so only when it takes a secular-democratic shape, an adjective which Abul Mansur Ahmad chose to describe his own political philosophy.

Mohammad Azam is Professor of Bangla at the University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments