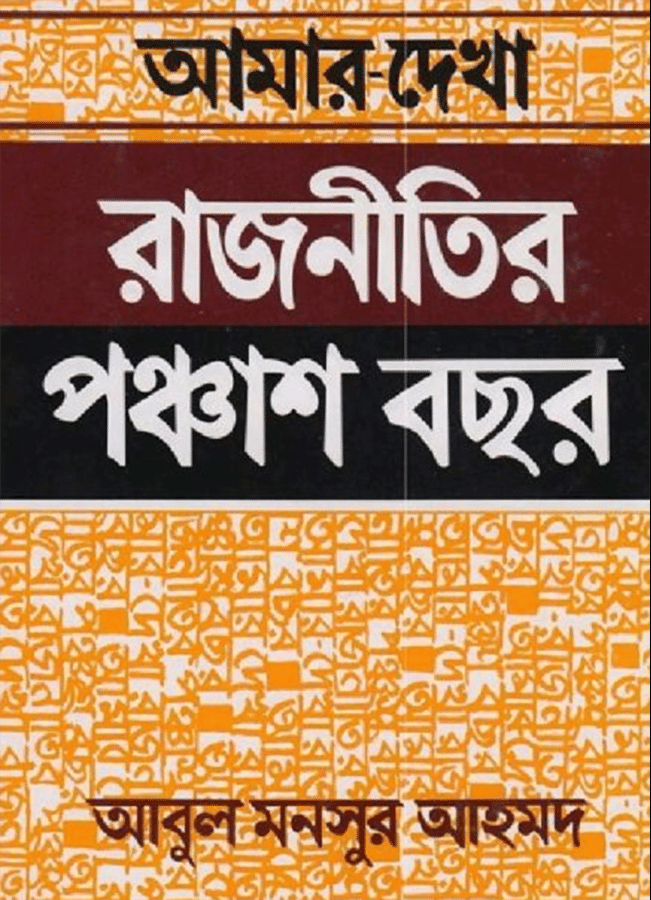

Reflecting on ‘Amar Dekha Rajnitir Ponchash Bochor’

As I delved into the autobiographical works of Abul Mansur Ahmad, it became evident that he had a penchant for plain speaking, avoiding embellishments. While crafting the first volume of my own biography, "Purono Shei Diner Kotha," I studied several Bangla autobiographies, including Ahmad's. I highly recommend it to anyone contemplating writing their autobiography, as his writing offers valuable lessons.

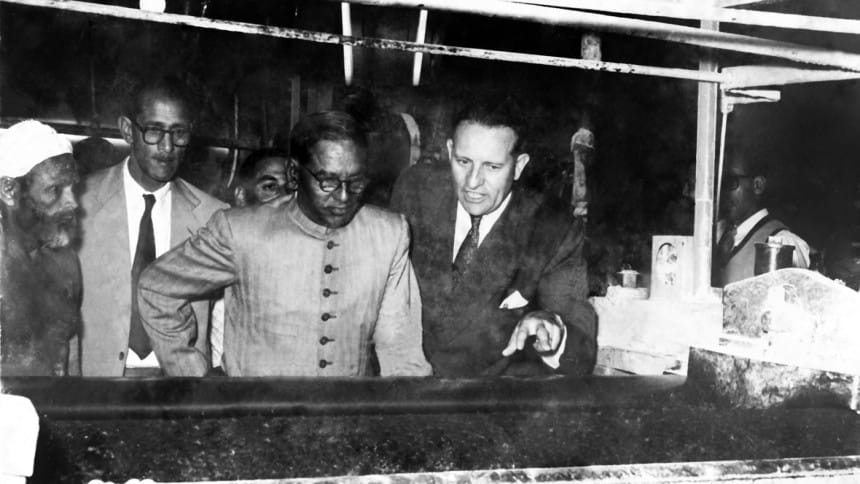

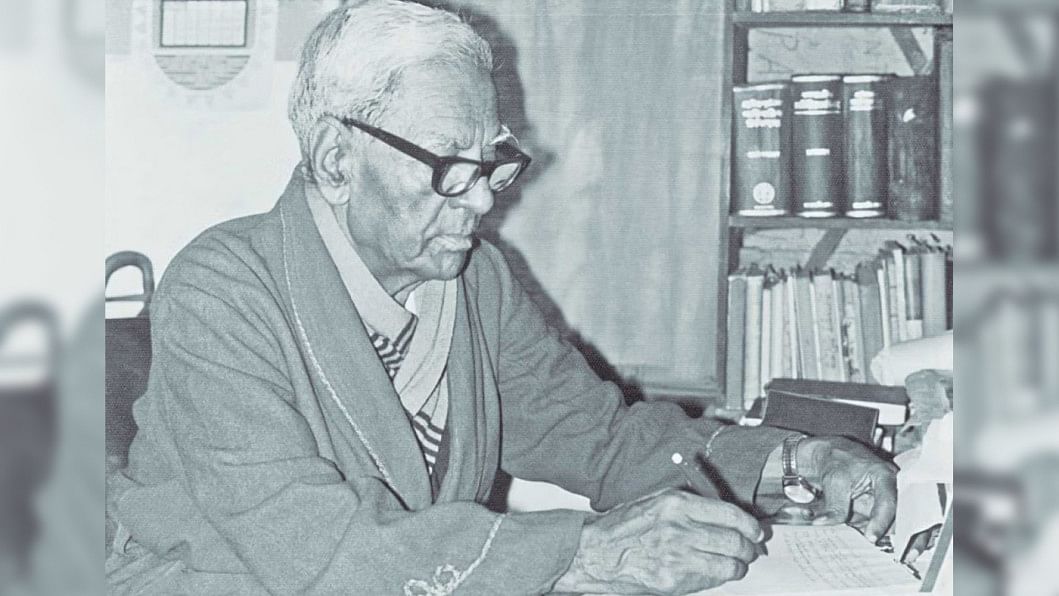

For a larger-than-life individual like Ahmad, writing autobiography is undoubtedly a daunting endeavor. He was simultaneously a journalist, an author, a lawyer, and a politician. These four unique characteristics were perfectly blended into his personality. Although he was a politician and a lawyer, he wasn't really a power-hungry person. He believed in lawful politics. As a politician, he considered it his duty to establish the rule of law.

T.S. Eliot observed a conflict between literature and journalism, but Ahmad saw it differently. As far as I can remember, Eliot wrote, "Journalists are busy with moments; they have no headache regarding the past and the future." However, he did not consider satirical literature, which is based on the present but, based on the need, can also become a part of the perpetuating future. Undoubtedly, Abul Mansur Ahmad is one of the most powerful satirical authors in Bengali literature. We see an eclectic mix of journalistic and literary elements in his satirical writings. If others can replicate his style, I believe Bengali literature will benefit immensely.

The book 'Amar Dekha Rajnitir Ponchas Bochor' has two unique features. In the book, he talked about politics as he saw it with his own eyes. He did not claim that others cannot have differing views. In fact, he did not even claim that only he was right; other people's political analysis is wrong. Instead, he mentioned that conflicting anecdotes help, rather than hinder the revelation of truth. I consider the book incomplete. It can be depicted as highlights of a few eras. During its publication, Ahmad mostly focused on the years 1948 to 1967—basically, 20 years. He despised the militant ruler Ayub Khan, but he did not overlook his contributions to Pakistani history, either. As a journalist, he never reached a verdict without considering all aspects.

He would consider the good and bad in every issue. He didn't simply favor the things that he preferred. For this reason, his friends would jokingly call him 'fifty-fifty Abul Mansur Ahmad.' Needless to say, this moniker refers to his habit of looking at both sides of the coin. For the same reason, journalists can also refer to Abul Mansur Ahmad's writings as testaments to neutrality. Let me give you an example regarding Ayub Khan. Ahmad wrote that Ayub Khan abolished the feudal system in West Pakistan. He effectively made monogamy compulsory. He acknowledged the financial inequality that existed in Pakistan. He also relocated several key offices of the Nikhil Pakistani Board to Dhaka.

I have been hating Ayub since my student life, and I believed he was only capable of doing evil deeds. Abul Mansur Ahmad opposed Ayub Khan's brand of politics, but at the same time, he also wholeheartedly acknowledged that he also did some good deeds. He also wrote about his misdeeds—he annihilated democracy, established dictatorship, broke down a federal state, and gave it a unitary form, broke apart the building blocks of Pakistan's formation, and injected military influence into politics by transferring the capital from Karachi to Islamabad, etc. His writings are unique in a way that he could very easily address the bitter truths of life. I truly doubt if anyone else can replicate this particular style. I will provide two examples here. The first one concerns Mahatma Gandhi. Ahmad held great respect for Gandhi, and he most certainly despised Gandhi's assassins. While expressing this hatred, he wrote, "Mahatma Gandhi was such a saintly person that even if he roamed around the African jungles in minimal attire, no wild animals or reptiles would cause him harm. It is unthinkable to cause harm to such an extraordinary person. To kill him, one could only find a follower of the Hindu religion. This proves that Hindus are the worst among humanity. At the same time, it was also proved that in today's era, Mahatma ji is the greatest and most illustrious human being. I believe this because Allah must have sent the saintliest of human beings to the worst of mankind so that they can get better."

Only Abul Mansur Ahmad could render such stringent criticism. At the same time, the words he used are not communal at all. He could criticize in this manner simply because he was a hundred percent non-communal at heart. The second example concerns political hypocrisy and deception. He brutally criticized both of these attributes of politics. He also vilified his own 'guru' Suhrawardi. And not only that, he also raised complaints of hypocrisy against himself, Sher-e-Bangla, Bangabandhu, as well as most other politicians. However, here I only quote his evaluation of Suhrawardi. He wrote, "Back in 1947, when he was a leader for East Bengal, I would get really sad to see him making the same child-like mistakes for 10 to 11 years straight. Amid such sadness, once I jokingly told him, 'Sir, thank the lord! You don't have a wife.' He was surprised and asked me, 'Why do you say so?' I replied, 'She would have given you 'talaq' by now. There is a hadith which states that if a Muslim is tricked thrice in the same manner, his wife gets divorced automatically. I am not sure whether this hadith is Sahih or Da'if, but it contains cautionary advice and some bitter truth in it.' At first, the leader laughed out loudly, but then he became somber and replied, 'One doesn't have to win all the time; they should lose occasionally too.' 'Listen, sometimes losses bring more greatness than wins do.'"

Undoubtedly, opportunist politicians try to gain favors by sacrificing their ethics, which is an impediment to the establishment of a democratic process. Whenever he saw politicians violating their moral values, he vehemently condemned them.

The most fascinating part of this book is his discussion of the role of a minister. He himself went through two stints of ministership—9 days as the regional minister and another tenure of federal ministership during the period from September 6, 1956, to October 8, 1958. He jotted down his experiences, from which we can discern that during that era, Pakistan's federal government was mostly being run by diplomats. The parliament members were elected mostly for show. In one chapter, he mentioned that during his tenure as a minister, he wanted to know the total amount of ammunition produced by Pakistan's military factories, but that information was not given to him. Even Prime Minister Suhrawardy did not have access to this information.

Ahmad named this ruling system as "Sikandary Khel (Sikandar's Play)." Then he went ahead and gave an illustrious description of how this 'play' created a divide between the eastern and western wings of Pakistan. He also eloquently portrayed how the head of state and the chief of staff were knee-deep in corruption.

Ahmad's political knowledge was not solely derived from books and journals. A significant part of this knowledge came from experience. He joined active politics as a supporter of the Indian National Congress during the Khilafat Movement. Congress was friendly with the feudal lords, who held some enmity towards the subjects. He organized the Krishak Praja Party in Mymensingh, which later flourished as a political party. Later on, he joined the Muslim League under Jinnah's leadership. Bengal had no importance in the Muslim League's sphere. But Abul Mansur Ahmad was a Bengali by heart and soul. Thus, after Pakistan's establishment, he became an integral part of the Awami League's formation procedure. Although he became inactive during the later periods of the 1960s, we can see from "Amar Dekha Rajnitir Ponchash Bochor" that he continued advising the Awami League until his last breath. He gave speeches supporting the federal ruling system within Pakistan's political structure and a two-tiered parliamentary system. He supported a combined election instead of separate elections. In most cases, his suggestions were ignored. However, he kept on speaking relentlessly.

Abul Mansur Ahmad was satisfied with the fact that the Lahore Resolution was materialized through the formation of Bangladesh. However, this statement can come under dispute. Because, there was no mention of two Pakistans in the resolution. Theoretically, there can be two or even more Pakistans based on the Lahore resolution. Will it be like that, or will the India stay undivided in the unforeseeable future—none of that can be determined right now. Apparently, he did not write much on this topic. But he left behind this question for us, and we should give it some thought. Ahmad's discussion makes one thing clear, which is, Bangladesh is not an upstart country. In this context, I am adding some information. In 1950, the world had 38 nations. The same figure increased to 138 and 203 in 1961 and 2015, respectively. Since the birth of Bangladesh, 58 new countries have come into being, and we are not sure whether more are on the way or not. The reason is, thanks to the overall global transformation, different sects are coming out with nationalistic claims. It is not certain that the nations of the world will stay fixed at 203; the number may very well increase.

Ahmad discussed Bangladesh's constitution in this book. He raised two types of questions. Firstly, he asked about the usage of the Bengali language in the constitution. He opines that the Bengali language used in writing the constitution should be maintained. Otherwise, building a rich stock of Bengali words will not be deemed possible. I am totally aligned with Ahmad that each and every foreign term need not be translated into Bengali. If we can write an English word in Bengali while keeping its original pronunciation intact, then there really is no need for inventing a different Bengali word for it. If this can be done, only then can we truly establish Bengali as the national language. Now we observe Ekushey February, we shed crocodile tears in remembrance of the martyrs, but none of us are truly doing anything for the Bengali language. How many foreign books are actually being translated in Bangladesh? How many books on economics, politics, international relations are getting translated? There are hundreds of such topics, and hundreds of books are getting published in the international arena. If we truly love Bengali and want to implement the Bengali language in all echelons of our daily life, then we have to translate all of these books. Who will translate them? Those who are supposed to translate them know neither English nor Bengali. Thus, translations are not happening, and we are lagging behind. In the current era, we need to eliminate the complexities of translation. As an example, we can maintain the legal word 'writ' and write it as "িরট" in Bengali instead of coining a new term. We can maintain the English terms for physics, chemistry, etc., and write the definitions in Bengali. If this is done, we can advance quite fast. I totally support this argument of Ahmad.

Ahmad's final verdict on the constitution is that it needs to be democratic. He wrote, "While the constitution of Pakistan was being created, I stressed ensuring the safekeeping of democracy in Pakistan instead of upholding Islam. Democracy will guarantee the upholding of religion automatically. In the case of Bangladesh's constitution, I said, in Bangladesh, society at large is not in danger—instead, democracy is under a lot of threat. Keep democracy free of all obstacles, society in general will flourish." He wrote some more on this, and I fully agree with his opinions.

I must say, I became a bit surprised because I have been speaking these same words for quite some time, and suddenly I realized that basically, I am relaying whatever Abul Mansur Ahmad has already mentioned. Our constitution has four pillars: nationalism, socialism, democracy, and secularism. My point is, if democracy does not exist in a country, it cannot establish secularism on a permanent basis. Thus, true secularism is only possible when democracy is firmly established.

Secondly, socialism. If we want to establish people's opinion-based socialism, there, too, democracy is required. Socialism void of democracy is something that is forcibly imposed upon the populace, which may not be sustainable. Thus, socialism also needs democracy.

Thirdly, nationalism. Bangladesh's nationalism has been nurtured, curated, and developed under the tutelage of democracy. Nationalism has no existence in Bangladesh without democratic movements. Thus, in order to reach the objectives of Bangladesh, only one thing is required, which is the establishment of democracy. However, there are many obstacles on this path.

Throughout his life, Ahmad fought for democracy. Establishing democracy is no walk in the park. Even in some developed nations, democracy is in dire straits. Voters need to stay vigilant to establish their voting rights. The voting system needs to be reformed. Democracy lovers need to maintain relentless research efforts. The ruling system needs to be changed. Many states in the world are changing their constitutional and democratic processes. Bangladesh needs to learn good practices from other nations. We all need to pay attention to five issues in this regard.

1. Choosing the people's representatives based on the voting ratio instead of the majority. If the government is formed solely on the basis of the majority, then it may turn into a dictatorship. Such an incident happened in Bangladesh before 2008. The European and Australian systems have already gone through such transformations. If this gets implemented, it will de-emphasize party-based political activities, and everyone will learn to work together towards a common goal. We need to conduct research on this from our country's perspective.

2. Ahmad wrote about a two-layered electoral system. In such a system, changes from election to election are often subtle and ensure uninterrupted social harmony. He talked about this in the context of Pakistan and Bangladesh.

3. Strengthening the local government. Ahmad opined that this feat cannot be achieved overnight. At least 10 to 15 years of experimentation are required for this to see the light of the day.

4. Passive democracy needs to be transformed, where a certain group consolidates all power. In this aspect, three kinds of reforms are necessary. Firstly, a referendum system. No new regimental regulations are required for this. England and Scotland organized such referendums. In order to achieve this, the constitution doesn't need to be reformed, and no new law is needed either. As the public is voting, and decisions will be taken on the basis of votes, such referendums can be enacted in Bangladesh. For cases where Bangladeshi laws are not acceptable or for determining which laws to enact, we can organize referendums. We need to work out the selection criteria for referendum topics, too. As an example, it can be the case that if 25 percent of the people want a referendum, the election commission becomes honor-bound to organize it. We need to give this more thought. Secondly, we can have a provision to democratically remove public representatives (upon certain grounds) through referendums. But this may be a far cry in Bangladesh's perspective. At best, this may be implemented at the local government level. Thirdly, the tenure of public representatives should be reduced to a couple of years instead of five years. But this may cause some unrest. We can consider the USA's example here. America's House of Representatives goes through a two-year election cycle. Senate elections take place once every six years. Thus, there are no overnight, major changes. If we can implement the two-layered election process, then we may think about enforcing the two-year tenure.

5. The legislative, executive, and judicial bodies should be given independence. At the moment, all state-related issues are under the control of the executive body. If the executive body has such dominance, the possibility of maintaining a liberal democracy dies a sad death. We should not allow this to happen.

Bangladesh's history is a combination of a number of great, enlightened individuals' personal histories. Abul Mansur Ahmad is one such glorious individual. May his thoughts, works, writings, and efforts live forever.

This is a translation of the speech delivered by the eminent educationist and bureaucrat Akbar Ali Khan at an event organized by Abul Mansur Ahmad Smriti Parishad on September 1, 2022. The speech was transcribed by Mohammad Abu Said and Emran Mahfuz and translated by Mohammed Ishtiaque Khan.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments