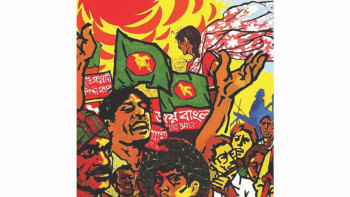

Bengal’s revolutionary journey through slogans

Political activism and slogans go hand in hand as external forces – from the British rulers to the Pakistan oppressors – have always been a threat to the mere existence of Bengali nationalism since the very beginning. The people of Bengal had always fought for their land and national identity, inculcating a massive cultural profundity as a result.

If we closely observe the political resistance and movement Bangalis have ignited and pursued across history, we'd see that each of the movements took place because of Bhat (rice grains) and land. Whenever an oppressive force tried to forcefully take their land and rice, the people of this country conjured up such resistance that even the strongest of forces had to retreat. Throughout this revolutionary journey, the historically and culturally rich Bangalees adapted political catchphrases or slogans that had the power and spirit to mobilise thousands in moments of national need.

From "Joy Bangla" to "Hok Kolorob," slogans arise spontaneously at times, driven by immediate needs, while at other times, they are meticulously crafted to serve a national emergency. These rallying cries, articulated in public assemblies, echo through the corridors of history, immortalising the voices of the unheralded heroes for generations to come.

Possibly, the most intriguing slogan of this subcontinent, marking the birth of the sense of nationalism of a cross-cultural country as "Bharat" (India) began with the song "Vande Mataram" from Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay's novel "Anandamath" (1882). The inclusion of this revolutionary song before the gathering at the 12th annual congress session of the INC (Indian National Congress) held in Calcutta in 1896 pioneered Bangalee's quest for freedom and its unique journey of pressing home the national needs through slogans.

In 1937, following the attainment of provincial autonomy, Sher-e-Bangla AK Fazlul Huq, through his elected party Krishak Praja Party, popularised two well-known slogans: "Langol Jar Jomi Tar" and "Gham Jar Daam Tar." In 1945, Tajuddin Ahmad introduced "Jomidar Nipat Jak" and "Jomidar Protha Uchched Koro." These slogans aimed to mobilise people from all walks of life leading up to the Partition of Bengal in 1947, advocating for a united and sovereign Bengal.

The 1928 resistance against the all-white Simon Commission marked a pivotal moment in the Indian independence movement, bringing together politicians from across the ideological spectrum in opposition to British rule. Following Mahatma Gandhi's "Bharat Chharo Andolan" (Quit India Movement) in 1942, "Jomidari Prothar Bilop Kor" in 1950, and National Leader Subhas Chandra Bose's proclamation of "Give Me Blood, and I Promise You Freedom" in 1944 spurred the realisation of the power of resistance and shaped the identity of Bengal as a nation.

Slogans such as "Keu Khabe Keu Khabe na, Ta Hobe Na, Ta Hobe Na" (1956), "Ye Azadi Jhoota Hai," "Sada Hatir Kala Mahut," and "Notun Botole Purono Mod" (1948), contributed to the bloodstained journey of Bangalees toward eventual independence."

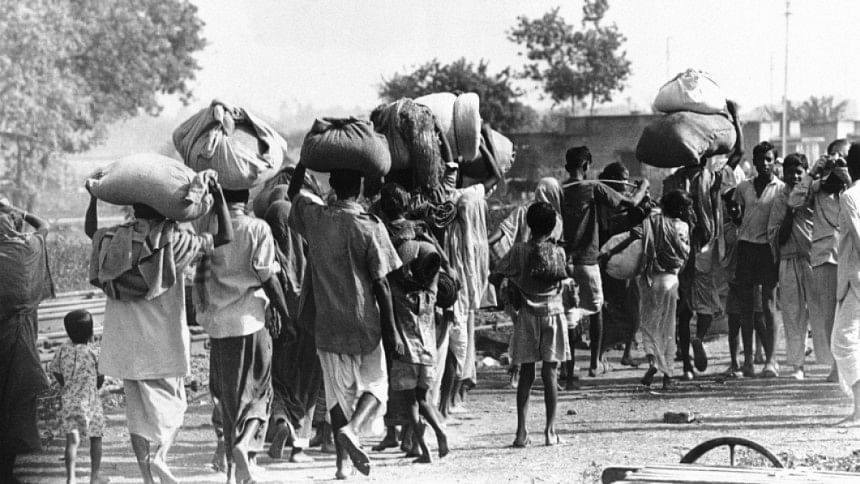

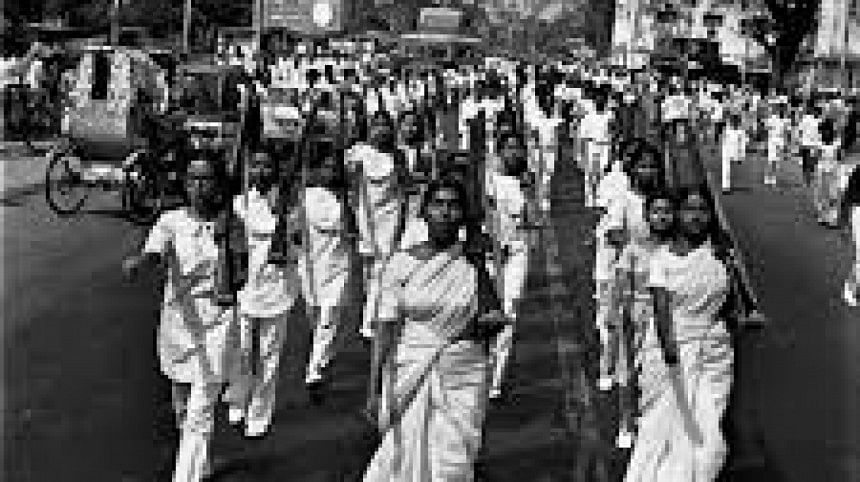

However, if we are to consider the single most event that shaped our national identity — it came with the Language Movement of 1952, where the mass killing of students took place on February 21, which ignited the spirit of revolution earning Bangla the honour and recognition of a state language with slogans such as, "Rastrobhasha Bangla Chai", "Banglai Arbi Akkhar Chaina", "Eksho Chuyallish Dhara Manbo Na", "Cholo Cholo Parishad Cholo" etc. These slogans spurred a nationwide resistance that encompassed the whole country, with students and activists coming to the streets to welcome a revolution never seen before. People were ready to shed their blood to protect their language and national identity, irrespective of the brutal opposition of armed Pakistani oppressors.

In the following year (1953), slogans such as "Nurul Islamer Kolla Chai," "Bangla Bhasar Rastro Chai," and "Gono Parishad Venge Dao," among others, were uttered to voice the unified aspiration of the Bangalee people for an independent and sovereign state named Bangladesh.

The 1956 slogan "Khete Dao Nato Godi Chhere Dao," the 1962 slogans "Samorik Shashon Mani Na, Mani Na" and "Down With Marshal Law," and the enduringly resonant slogan "Jwalo Re Jwalo, Agun Jwalo" were introduced during the 1962 East Pakistan Education Movement.

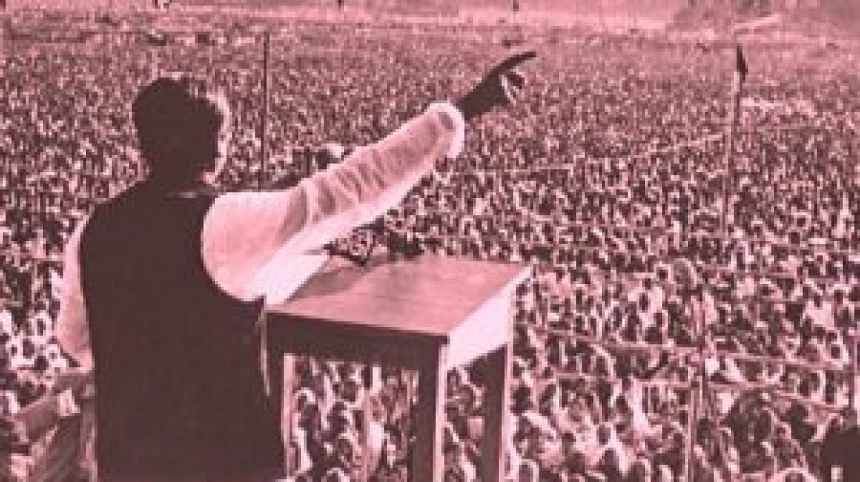

In 1966, while presenting his historical Six Point Movement, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman historically said to one of the Pakistani officials, "Actually, we only want one thing (sovereign, independent state), I just broken it down to six points for your (Pakistan) betterment." At that time, slogans such as "Bangaleer Dabi Chhoi-Dofa", and "Bachar Dabi Chhoi-Dofa", presented the Banglee people with a unique sense of self and nationalism, where their leader Sheikh Mujib, could present and negotiate the terms for his countrymen.

The latter history is marked by the incessant imprisonment of national leaders and the people's consistent resistance to free their countrymen and their country from Pakistani oppressors. During that period (1968-1971), slogans such as "Jago Jago Bangalee Jago", "Jail Er Tala Bhangbo, Sheikh Mujib Ke Anbo," "Mittha Mamla Tule Nao," "Greftar Dharpakor Cholbena," "Songbadpotrer Shadhinota Chai," "Rajbondider Mukti Chai," "Pradeshik Shwayottoshashon Dite Hobe," and "Tumi Ke Ami Ke, Bangalee, Banglaee" were the motto of the masses and political activists.

The evolution of slogans somewhat transcended into brutal ones with belligerent catchphrases like "Krishak Sramik Astra Dhoro, Jonogonotantra Kayem Koro," "Ayub Monayem Dui Bhai, Ek Dorite Fasi Chai," "Bhhoter Age Bhat Chai, Noile Eibar Rokkha nai," "Muktir Ek E Poth, Soshostro Biplob" and so on.

At this time, a catchphrase, "Joy Bangla", from national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam's "Purna Abhinandan" poem, which was previously utilised in the 1922 resistance, has been popularised by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1971 in his quest to free the country from Pakistan. The slogan became a statement to liberate the country from the occupation forces, combining all their spirit and strength for an independent nation named "Bangladesh" for the first time.

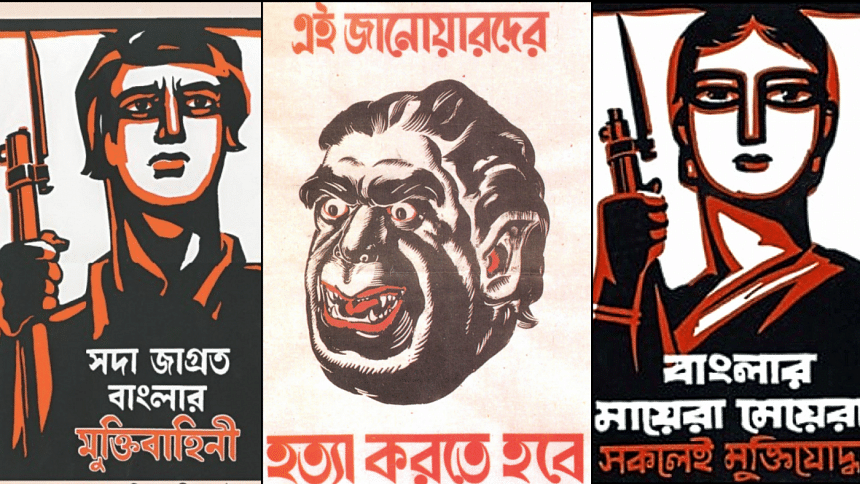

During the 1970-71 period, the formation of slogans took its course with unique development as people began to take snippets from Bangabandhu's addresses to utilise them in their political rallies, posters and graffiti. Slogans such as, "Ghore Ghore Durgo Gore Tolo," "Aposh Na Sangram, Sangram, Sangram," "Beer Bangalee Astro Dhoro," "Grame Grame Durgo Goro," "Mukti Bahini Gothon Koro" became the central anthem of Banglaee people leading up to and during the War of Liberation of 1971.

When analysing slogans in relation to politics and Bangladesh's journey towards independence, it is evident how they are intricately connected to our national journey as a nation. Slogans were never merely catchphrases to prove a political point; in the case of our independence, they emerged spontaneously as an immediate necessity.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments