‘Bidrupe Bidroho’ and the anatomy of satire as resistance

"Bidrupe Bidroho", the six-day exhibition currently underway at La Galerie, Alliance Française de Dhaka, revives the spirit of resistance. Organised by Earki, the exhibition has been organised to mark the first anniversary of the July 2024 uprising, the 36-day-long people's movement that culminated in the overthrow of the Awami League regime. Notably, instead of news clippings or political slogans, "Bidrupe Bidroho" remembers the stories and memories through cartoons, memes, graffiti, installations, interactive games, and irony-laced performances. It is a political experience crafted with the use of laughter. As I stepped into the space, I realised that this was not a walk through a gallery, but one through memory, and the feelings of outrage and defiance.

Satire, after all, has long been more than witty humour. It is a tool of resistance—sharp, disarming, and often the only language that remains when every other form of speech is silenced. Last July 2024, when censorship deepened, internet shutdowns became routine, and police violence escalated, people fought back with humour and sarcasm. They responded to authoritarian absurdities with absurd antics of their own. Cartoons of ministers fleeing in boats went viral; memes mocked official statements and exposed contradictions more effectively than press briefings ever could. What satire offered was not just comic relief, but a reclaiming of power. It allowed people to ridicule dubious authority, to critique without fear, and to mourn through mockery. It was an emotional release and a political strategy rolled into one.

This isn't the first exploration of satire as protest for Earki. Last year, in the aftermath of the uprising, they co-hosted "Cartoon e Bidroho" at Drik, showcasing the political cartoons that had exploded across social media in July. The exhibition captures the immediacy of the moment and artists who, after years of silence, found their voices and used cartoons to demand change. "Bidrupe Bidroho" builds on that momentum. It does not just archive what was created in protest but attempts to allow viewers to relive it.

The exhibition opens with life-size cartoon cutouts that recreate some of the most iconic visual moments from July. Among them, a satirical rendering of Salman F Rahman and Anisul Huq fleeing in a boat instantly pulls you back to the chaos of those days. Just beyond this visual humour was a carefully curated corridor that provides structure to the madness through a chronological timeline of July. The timeline is perhaps the exhibition's most grounding feature.

Visitors walk through a hallway where each stretch of wall is dedicated to a key phase of the uprising: when it began, how it evolved, what sparked public fury, how social media influenced the narrative, and finally, the dramatic toppling of the regime. Protest hashtags, screenshots of viral posts, and symbolic graffiti come together to tell a collective story of frustration, courage, and imagination. The corridor documents what people were saying, doing, and feeling, and in a way, forms the emotional spine of the exhibition.

Moving past the timeline, things begin to shift from narrative to experience. The exhibition does not want you just to see protest—it wants you to play it, laugh at it, be disturbed by it, and sometimes, become part of it. Right outside the gallery, I was greeted by "Haon Uncle-er Bhaat-er Hotel" — a playful takedown of how Harun Or Rashid, former chief of the Detective Branch of Dhaka Metropolitan Police, attempted to coerce student coordinators into making televised statements under duress.

The organisers leaned into experience over decoration. After entering the gallery, a life-sized Snakes and Ladders game caught my eye. It lets you play through a twisted version of Bangladesh's political history, where every roll of the dice is rigged. The game board is redesigned to resemble the AL regime's manipulations, turning every potential leap forward into a forced backslide. Then comes one of the most haunting installations: a dark room lit only by the glow of a computer that has no internet. Instead, a dinosaur game plays on repeat, while Zunaid Ahmed Palak's contradictory statements echo through speakers, first blaming cable fires, then citing spontaneous outages, and finally promising reconnection once the situation improves. The walls are plastered with screenshots, headlines, and images of the events, as we remained confined in our homes amidst a forced internet shutdown, giving shape to the paranoia and isolation brought on by the blackout. It is satire pushed into unease, and it works.

The most prominent installation is that of Sheikh Hasina, portrayed in a looming cutout with seven buttons you can press. Each button plays a different speech, from her most emotional appeals to bizarre moments like breaking into recipes or recounting personal tragedies. I had a fun time playing each button, and listening to the familiar voice envelop the room as I stood in front of her not-so-perfect doll-sized figure. Not far from this is the corruption mountain, an art piece constructed entirely from real newspaper clippings of corruption scandals. Hanging from it are strings, and when you pull one, a corrupt figure pops up. When I tugged at a random string, Salman F Rahman appeared. The installation feels like a carnival game until you remember that every figure who appears was part of the machinery that crushed dissent.

One of the most creative corners is a puzzle made of cardboard cutouts that represent the ideal elements of a dream Bangladesh. Visitors are invited to piece them together. In the act of building, they are reminded of what July's protests were really about: constructing a better future from a fractured present. There is also a spinning pinwheel where each number you land on gives you a message; something you would hypothetically say to Hasina. Some are hilarious, some cutting, others heartbreakingly sincere. Across the room, a treadmill dares you to run faster than fascism. A video of Hasina plays on screen, taunting you with the phrase "Hasina palay na" as you try to catch up with her speed.

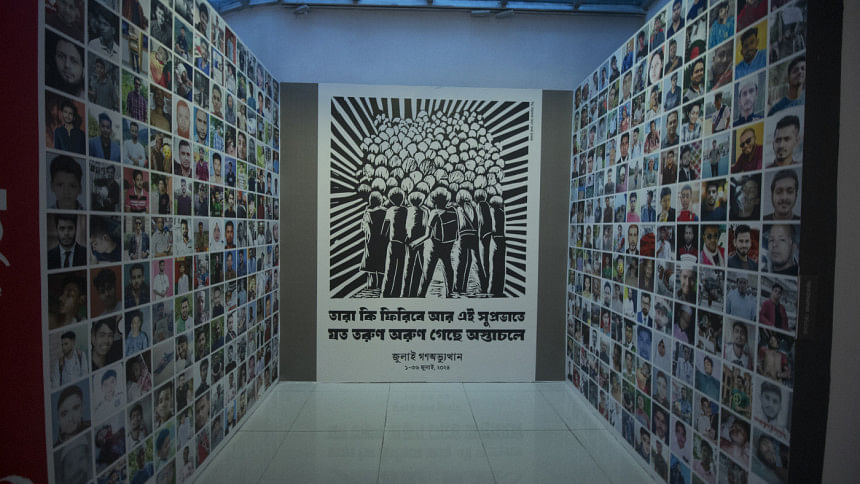

Yet for all its humour, the exhibition does not forget the price of protest. In a quiet corner, portraits of the July martyrs hang solemnly. Their presence is a reminder that the arrangement is not just a moment of satire but one of sacrifice. Nearby is a display of the actual "weapons" used to silence protest: guns, helmets, knives, hammers, and even razors. Presented like artifacts in a museum, they jolt you into remembering that what you are laughing at was deadly serious. Memes and illustrations developed by Earki during July were also presented en masse, most of which went viral during the uprising. These represent how people made sense of chaos, grieved, resisted, and mobilised.

"This exhibition is meant to capture the collective experience of July—not just the politics, but the emotions—because July meant something to each of us," explained Simu Naser, founder and editor of Earki. "We did not want people to just come and look at things. We wanted them to remember, to feel, to play, and to mourn. That is what satire does—it makes you part of itself." And indeed, "Bidrupe Bidroho" does exactly that. It walks the line between pain and playfulness, sarcasm and sincerity. It honours the memory of resistance not with solemnity alone, but also with a kind of wit that stings, lingers, and leaves you thinking long after you leave. Because in a country where political speech is policed, where history is rewritten, and where reality is too often absurd, satire becomes not just entertainment but evidence. It reminds us that we saw what we saw, felt what we felt, and lived through what they want us to forget.

"Satire has always been a weapon of the marginalised; a way to laugh at power and expose its absurdities," he added. In July 2024, this same kind of satire fuelled resistance, achieving three crucial things: it undermined fear, seized narrative control, and archived collective memory. A mocking cartoon can travel farther than a speech, a meme might reach more people than an editorial, and a graffiti image will outlast a tweet. In oppressive contexts, humour becomes a silent roar. And by turning that humour into art, Bidrupe Bidroho ensures that the spirit of July will not be erased; it will wittily become legendary.

The exhibition is open to all till July 36 (August 5) from 3pm to 9pm.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments