A city gasps, a park resists: Panthakunja protest redefines civic action

On a drizzly afternoon in Dhaka, where traffic fumes mix with the noise of construction, a quiet but determined protest unfolds at Panthakunja Park. Panthakunja has become the front line for Dhaka's cultural resistance. There are no street blockades here—only guitars, paintbrushes, puppet shows, and poetry. For over six months, artists, writers, urban planners, and ordinary citizens have transformed this endangered green space into a stage of creative resistance, camping on park grounds and enduring bitter cold, dust, summer heat, and monsoon rains.

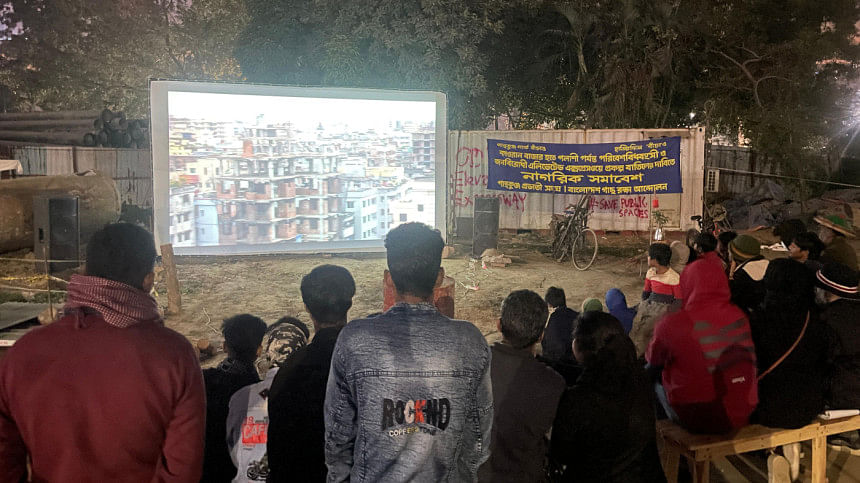

Over 45 cultural events have taken place during this time—ranging from sports events, music recitals, performing arts, street plays, critical discussions, and environmental lectures to medical camps and art workshops for children. The aim is not performance for its own sake but to awaken public consciousness and demand accountability. Artists and illustrators across the country and abroad have also expressed their solidarity through digital arts, illustrations, animations, stop-motion films, and more.

"This is a fight to protect not just trees, but memory, air, childhood, and biodiversity," said Amirul Rajiv, coordinator of the Bangladesh Tree Protection Movement. "We are trying to defend what's left of Dhaka's soul."

Panthakunja, located on Sonargaon Road, was once a rare oasis in the capital, lush with native trees, birds, and daily visitors. But the park has suffered years of neglect and encroachment. First came a long enclosure by the Dhaka South City Corporation in the name of beautification. Then came the Dhaka Elevated Expressway project, which has now taken over two-thirds of the park.

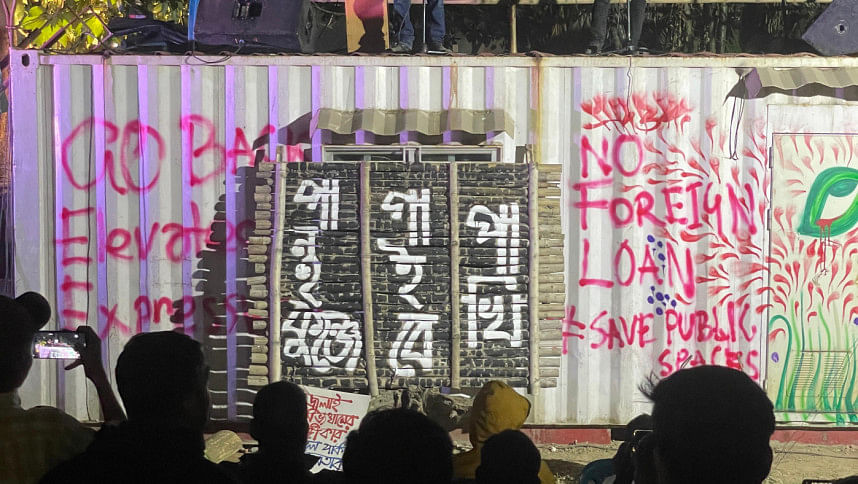

Where thick greenery once stood, there are now gaping holes and concrete piles. A massive boring machine remains abandoned mid-operation, surrounded by fences and slogans. In the heart of this altered space, protestors have created a new landscape—sculptures, murals, tents, and even a makeshift stage for performances.

According to environmentalists, over 2,000 trees have been felled in Panthakunja and Dhanmondi alone, part of a citywide toll of more than 4,200 trees lost last year. Activists claim that construction is ongoing without valid environmental clearance, as the original permit expired in December 2023 and was never renewed.

Despite these violations, government's response has been minimal. Three senior advisers visited the protest site in December, acknowledged concerns, but made no commitments.

Still, the resistance continues. Every week, the park hosts a variety of cultural programmes that draw in local families, students, and passersby. "Children now call this 'the camp where the tree people sing,'" said one volunteer.

Rajiv explained the strategy behind this unique form of protest, "This protest is born from common sense and social conscience. Dhaka ranks among the most climate-vulnerable cities in the world, yet there's very little effort to preserve its parks and water bodies."

He continued, "Panthakunja is just one example of how our governance is failing the capital's ecological balance. Dhaka North City Corporation (DNCC) has playgrounds and parks in only 16 of its 54 wards, while Dhaka South City Corporation (DSCC) has them in only seven of its 75 wards — and most of those are either misused or leased out. Over two million people rely on these spaces directly or indirectly."

"We're not just resisting tree-cutting," Rajiv said. "We're protecting what makes this city liveable. If even one bird finds shelter or one child grows up with clean air because of our protest, that's reason enough to continue."

Naim Ul Hasan, another coordinator of the Bangladesh Tree Protection Movement, added, "One of the major focuses of our movement is to make people realise that the issue of the environment is universal and impacts us all. So, we tried to make the movement as inclusive as possible by incorporating people from all sorts of backgrounds. Moreover, we felt that the environmental discourse at the policy level in our country is still stuck at a primitive stage. We want this movement to start a deep ecological discourse at the policy level."

Rajiv described how the movement has deliberately avoided aggression. "We've designed this as a cultural resistance—over 45 events, from concerts and film screenings to art installations."

"This is no longer just a protest—it's turning into a full-fledged citizen movement. We've spoken with local communities. They're with us. Cultural expression helps people connect to the cause in ways that facts and figures often cannot."

The contradictions are stark. While the city corporation has raised concerns about the expressway, it has also built a garbage transfer station and a public toilet within the park. WASA, Drinkwell, and even private corporations have claimed pieces of this five-acre park.

The wildlife feels the impact, too. "Birds were visibly disturbed after the last tree-cutting in December," Rajiv noted. "They were here before us. They have as much right to this land as we do."

On the 168th day of the sit-in protest, a public hearing was organised where the coordinators presented their case to a panel of judges consisting of Prof Giti Ara Nasreen, Prof Anu Muhammad, Dr Iftekharuzzaman, Jyotirmoy Barua, and Shamsi Ara Jaman. After hearing the case, the judges called for halting the construction work in the park and reopening it to the public. They also requested the activists to pause the sit-in protest for now.

As the monsoon clouds build, the sit-in protest is paused, but the performances at Panthakunja will continue, insisting that the fight for a park is, ultimately, a fight for a liveable future.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments