Documentary photography: A journey from truth to interpretation in visual storytelling

Storytelling through pictures is an ancient concept that has existed for generations. What breathed new life into the practice of telling stories through pictures was documentary photography, which integrated a crucial social purpose. Documentary photography aimed to portray, in a manner more informal than was generally practised, the everyday lives of ordinary people to other ordinary people.

This simple idea—capturing and presenting the "everyday life" of the "ordinary"—became rapidly and widely popular in the early twentieth century. Its dominance has since waned over the years, but a modern notion of social documentary has emerged, shaped by the proliferation of media products in the twentieth century.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the rise of large-scale mass printing presses opened a new domain for documentary photography to flourish as a popular movement. The photographer became a crucial new media fieldworker, and their work became a core element of filling the pages of mass-printed magazines and newspapers. Photo agencies emerged to represent the interests of these photographers. Western photographers ventured into various settings, bringing photographs home and bearing the responsibility of documenting everyday life. They acted as reporters, fulfilling a responsibility to engage in what could be considered a 'humanistic act.' Their efforts produced pictures and, occasionally, accompanying stories.

The formal aim of social documentary was initially to keep records, but by the 1930s, it evolved to enlighten and educate. Photographers gathered images to develop a 'picture story'—a sequence of images that visually narrated incidents, with minimal text descriptions for context. These photo stories were powerful, capturing the world "in motion," and representing people and their range of emotions—whether smiling, crying, angry, or vulnerable in moments as ordinary as any other in their daily lives.

As time passed and technology advanced, social truths became more embodied in the act of documenting. Thus, documentary photography emerged as a tool within a broader movement of social change and liberal attitudes. Documentary photography had a mission: to inform the wider population, to encourage them to become aware, and, in doing so, to also inform themselves about "the common people." Social documentaries became focused on constructing the concept of the public realm through shared social experiences. Today, the aim has diverged significantly from the traditional notion of photography as merely a "document" or a form of proof.

A new understanding developed during this process: the idea that "the way of seeing is also a way of knowing"—that "vision is knowledge." In essence, the more one sees, the more one observes, and the more one is attuned to their senses, the more it equates to knowledge, which in turn improves humanity. This concept of "seeing" as "knowing" was regarded as "True" or "Truth," often associated with factual evidence. The notion of photographic evidence gained prominence with documentary photography, becoming a popular synonym for truth. Thus, visual proof was paired with a strong pedagogical and judicial tone.

In 1935, Roy Stryker, an economist, government official, and photographer, was appointed as the head of the Historical Section in the Information Division of the Resettlement Administration, later known as the Farm Security Administration, during the Great Depression. He launched a photography programme to document the organisation's activities, believing that the medium was crucial for the administration's work. He required his photographers to familiarise themselves with the situations they were documenting in the field.

Photographer Theo Jung disagreed with this approach, preferring to rely on his instincts. Stryker's deliberate approach and Jung's on-the-spot decision-making differed fundamentally, leading to Jung's dismissal.

The Farm Security Administration programme focused on farming communities and small towns. The photographers believed their work was highly significant, even if only to one man at their headquarters. People tend to seek comfort by living in denial, which can be fueled by propaganda. However, propaganda is rarely successful in the long run, and as propagandists, Stryker and his team were never very successful.

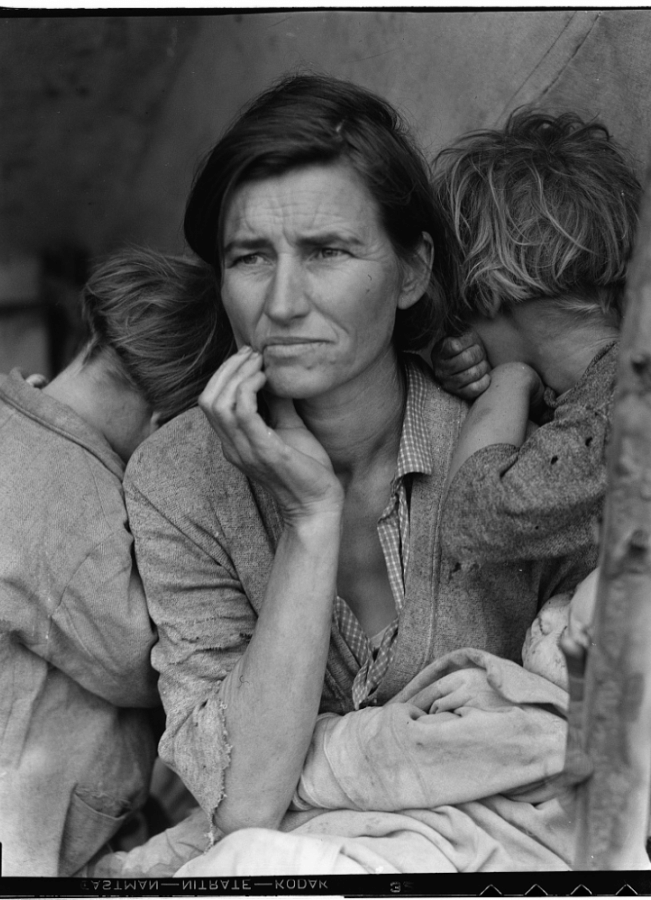

Stryker considered Dorothea Lange's "Migrant Mother" to be the ultimate photograph and chose it for the cover of "In This Proud Land". However, Stryker's organisation prided itself on the "naturalness" of photography—moments that were organic, unfabricated, and unmanipulated. It pained Stryker to learn that the "Migrant Mother" image had been posed. Photographs that went against these principles of naturalness would have been considered propaganda and, therefore, untrustworthy. So, when Arthur Rothstein moved a steer's bleached skull in drought-stricken South Dakota for a better picture, it naturally caused some trouble.

There are various ways to portray or narrate social stories. How stories are made visible—through the strategies employed—can influence the ambition of documentary work. Documentary photography is not merely about preserving historical modes of expression but about renovating and discovering new avenues of storytelling.

The realm of documentary photography exists at the intersection of art and journalism. It applies "creative treatment" to the concept of "actuality." This means that the "reality" of any subject is, in essence, its interpretation of real life. What remains important is that an interpretation exists and that the interpretation has depth and insight, or some measure of "profundity." Essentially, documentary photography does not possess an essence of "factual truth" but rather presents interpretations of human actions as seen through the eyes of the observer. So-called "objective" and "descriptive" photography provides a more detached, disengaged perspective on the scenarios it depicts.

The need, desire, and yearning for the recognition of "reality" do not exist solely in the hearts and minds of photographers or their subjects but also involve the spectator.

Documentary images suggest that there is a particular perspective or viewpoint from which a photograph must be viewed. But the "politics of vision" come into play in how an objective, documented photograph is interpreted by a spectator when it is seen as a source of knowledge. The viewer is forced to confront reality, but "confronting reality" is something humanity has historically struggled with. Its extension and shadow stretch across societies, manifesting as "denial."

Today, "denial" is a popular concept, referenced in magazines and applied by people who may not even be aware of its psychoanalytic origins. The same applies to teachers, students, and virtually anyone who has seemingly been "in denial" of an obvious truth or reality that is evident to everyone around them. Thus, if a documentary fails to fully succeed in altering the mindset of its audience, it should not come as a surprise, even if it engages the viewer with "interesting" photographic images.

The concept of documentary must constantly reinvent itself as time goes on. It must adapt to new strategies for new audiences, each of whom has different demands and values. This has led to documentary photography finding various voices and spaces, facilitated by the media and the spectacle culture of contemporary times. A new openness has emerged toward photography as contemporary art in institutions.

Gazi Nafis Ahmed is an internationally renowned artiste working with photography and video. He has taught at the Danish School of Media & Journalism, Complutense University, Istituto Europeo di Design Madrid, and Lens School of Visual Arts and is an honorary fellow at Columbia University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments