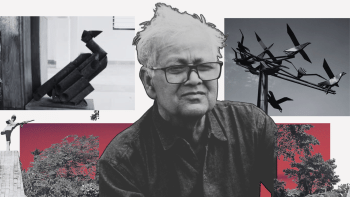

Remembering Hamiduzzaman Khan, the sculptor who shaped a nation’s memory

"Art and life are one"—few artists in Bangladesh embodied this philosophy with as much integrity, conviction, confidence, and creative urgency as Hamiduzzaman Khan. His passing on Sunday at the age of 79 is not just the loss of a preeminent sculptor, but of a conscience carved in steel and stone—a sculpted voice that dared to remember when forgetting would have been easier.

For decades, his works stood sentinel across the landscape of this country—quiet but powerful witnesses to our struggles, our resilience, and our history. "Sangsaptak", perhaps his most defining piece, looms outside Jahangirnagar University's central library like a frozen cry. The one-armed, one-legged figure of the Freedom Fighter surges forward with a broken body but an unbroken, unyielding will. It's more than a sculpture—it's our national psyche cast in metal. It is pain, persistence, and protest in a beautiful structural form.

And then there's "Bijoy Keton" at the Dhaka Cantonment, or "Jagrotobangla" in Ashuganj—monuments not merely to the Liberation War, but to the idea that memory must be inscribed into the public sphere, not hidden in textbooks. Hamiduzzaman didn't just sculpt statues—he shaped narratives, engraved resistance, strength, and the vigour of freedom into the cityscape, demanding remembrance as a civic act.

Though too young to bear arms during 1971, he bore witness. The brutality of the Pakistani army, the genocide, the trauma of a ravaged homeland—these were not abstract horrors to him. They became the lifeblood of his creative vocabulary. You see it in the lines, the thrusts, the defiant gestures of his forms. His art didn't simply represent the Liberation War—it embodied its urgency in all its might.

What is most striking is how his work fuses the mythical vigour of Bengal—its people, memory, and the nature that surrounds it. There is a timelessness in his use of form—those elegant, often exaggerated yet precise figurations; the interplay between mass and void; the circular shapes that invoke planetary rhythms. His sculptures evoke the ancient with modern stylisation and urgency all at once. They could sit in a museum a thousand years from now and still make sense. The whole spirit of the Liberation War lives in each of his sculptures—unyielding, unbent, pointing toward liberty, like a wounded mother crying for revenge, redemption, and for her child.

But his reach extended far beyond the war. In "Unity" at Bangladesh Bank, "Freedom" at Krishibid Institution, and "Swadhinata Chironton" at Bangladesh Open University, he created spaces for contemplation. These are not didactic works. They don't scream nationalism. They invite the viewer to inhabit the spirit of liberty, to reflect on what freedom feels like—not as policy, but as breath, motion, muscle, and memory.

The artist's command over material was masterful—bronze, cement, steel, marble, granite—each treated not just as medium but as metaphor. A bronze body becomes both a relic and a revolt. A marble wing evokes the soul's yearning. Hamiduzzaman's forms, whether abstract or figurative, always carried weight—not just physical, but emotional and historical.

The personal dimension of his work must not be forgotten. The ardent artist was a man of deep introspection—often restless, always searching. His solitude found expression in his watercolours—glowing, contemplative pieces that feel like whispered memories. There's tenderness here, a kind of emotional chiaroscuro, as though light itself were mourning something lost.

His portraits—minimal, precise—tell stories in silence. A boy's gaze in pencil, an old man's lined face in ink. In his "Reflection", "Riverscape", "Summit" series, he depicts the nature of Bangladesh like never before. The quiet movement of the shapes in a still painting gives away a melancholic yet hopeful, serene, solitary introspection. These are quiet works, but not without power and strength. They speak of lives lived in the margins, in transition, in witness.

Few Bangladeshi artists have shaped our national consciousness as deeply as Hamiduzzaman. He helped define what public art could mean in this country—not decoration, but declaration. That his sculptures are installed at the Olympic Park and Sancheong Sculpture Park in South Korea, or at the World Bank in Washington DC, speaks not only to his technical brilliance but to the universality of his themes—resistance, sacrifice, dignity, endurance.

Yet he remained deeply rooted in this land. His art was born of soil, blood, river, and struggle. There was never any pretense in his work—only precision and truthful recollection. His commitment to form—especially the dynamic interplay of human and natural imagery—remains unmatched. He reminded us that we are part of nature, and like nature, we must find ways to survive, to adapt, to rise again.

Hamiduzzaman Khan's demise leaves an aching void in our artistic landscape. But in truth, he hasn't gone anywhere. He lives on in every steel silhouette that reaches skyward, in every bronze hand that still clenches with purpose, in every abstraction that dares to hold a nation's grief and pride in the same breath.

He once said he found peace in his work. And now, through his work, he has gifted us a kind of peace, too—a peace built not on forgetting, but on remembering with courage.

Beyond formal accolades, his legacy lies in shaping how a nation sees itself.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments